Boris Johnson Confronts a Swedish Obsession

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Whenever you hear a policy that touches on pubs in Britain, you know it’s serious. With coronavirus infections and hospitalizations rising, Boris Johnson is preparing new lockdown rules, including shutting down boozers and restaurants in the north of the country. That has sparked a bitter debate among his cabinet, his party and the public about whether his caution is costing too much.

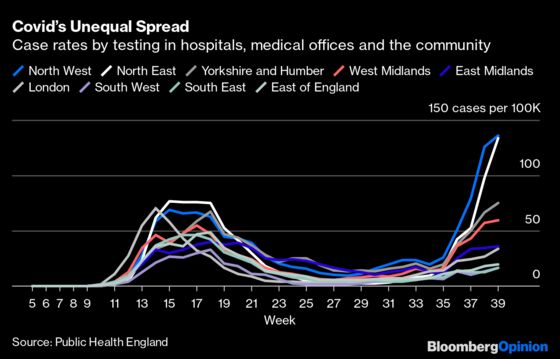

As so often in this pandemic, Scotland has gone first, closing pubs and restaurants for a 16-day “circuit-break” to try to curb infections, even though the Scottish infection rate is still far below English cities such as Manchester, Liverpool and Newcastle. The new measures for the north of England appear to mirror the Scottish lockdown, only without the time limit.

Johnson must now, in a sense, choose between Scotland’s vigilance and Sweden’s looseness in confronting the virus. The first approach would anger a vocal part of his Conservative Party, which thinks the prime minister’s lockdowns have been been misguided and ineffective. It might also weaken Tory support in northern England, a former Labour stronghold that helped deliver Johnson’s December election victory.

If, on the other hand, he did bow to pressure for a more laissez-faire Swedish approach and cases kept rising, the National Health Service may be overwhelmed. He would be blamed for any loss of life. If Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s measures proved more effective, the political damage would be considerable.

The calculations for Johnson are unenviable. He has always defended his Covid strategy by saying that he’s following the advice of government scientists. That defense is looking shaky. First, the advice doesn’t seem to be very good. Local lockdowns aren’t working. Labour leader Keir Starmer points to increased infection rates in 19 of the 20 areas in England that have been placed under special restrictions for two months. Either enforcement needs to get better or the rules changed. Overcentralized policy decisions haven’t helped.

Second, scientific opinion is increasingly divided. A new study from University of Edinburgh scientists concludes that England’s lockdowns prevented the NHS from being overwhelmed but prolonged the epidemic and increased the country’s total number of deaths.

Thousands of biologists and medical professionals have signed what’s being called the Great Barrington Declaration, which makes a compelling case against lockdowns: Children don’t get vaccinated; people with cardiovascular disease don’t get timely treatment; cancer screenings are delayed and mental-health problems mount. All of this will mean more excess deaths in the future, they argue.

Sunetra Gupta, the Oxford University epidemiologist who challenged the Imperial College model that informed Johnson’s first lockdown, is one of the declaration’s authors. The problem is figuring out what to do instead.

The prescription of Gupta and her co-writers, supported by many Tories, is effectively the Swedish herd immunity strategy that was dismissed as unworkable and morally repugnant at the start of the pandemic. The signatories argue that while most people should go about their normal lives without restrictions, those at highest risk of getting a severe form of the disease can be shielded, a policy they call “focused protection.”

Not everyone agrees this is desirable. A number of dissenting scientists note that herd immunity to coronaviruses wanes over time. And there are huge practical challenges in segregating the vulnerable. The Barrington declaration also fails to note the potential impact of “Long Covid,” the persistent virus aftereffects that prove debilitating for many sufferers.

Neither does it address the nasty ethical problems in a policy that isolates one part of society (raised by my colleague Andreas Kluth recently). “Ethically, history has taught us that the notion of segregating society, even perhaps with good initial intentions, usually ends in suffering,” wrote Stephen Griffin of Leeds University’s School of Medicine.

Gupta has argued that a degree of “cross-immunity” from exposure to other coronaviruses lowers the threshold for herd immunity. If so, getting there might be easier than was initially thought. But that we’re still debating herd immunity six months after the first pandemic wave shows how little we’ve learned about Covid-19.

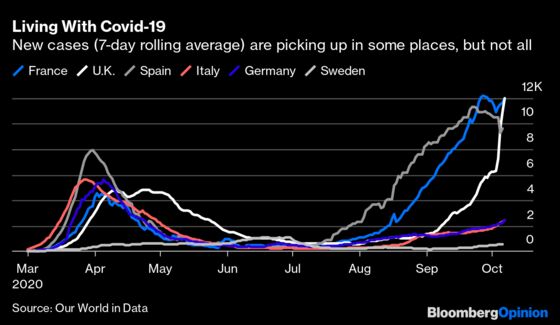

Much of the science on immunity and the virus’s spread is unsettled. Even Anders Tegnell, the feted architect of Sweden’s approach, says it’s too early to judge whether his experiment has been a success. He didn’t rule out new restrictions when cases in Stockholm rose last month. The Swedes — whose health-care system was creaking at the first peak of the virus — have been quietly adopting measures, such as increased testing, that they initially eschewed.

The absence of definitive scientific answers puts the onus on politicians to find a mix of policies that offers us both freedom and protection. Tegnell believes that if the disease is going to be around a long time, then containment policies have to be sustainable — which most lockdown rules aren’t.

In Britain, support for lockdowns, while still strong, has been declining as the economic toll becomes clearer. Nevertheless, Johnson can’t really take the Swedish route. Britain’s lack of a functioning mass-testing system, its overstretched health service and the lack of trust in the government’s Covid management suggest this is not the time to let the virus rip.

The best Johnson can do now is something Sweden and Scotland have done well, and he has done badly: Make a clear plan and explain it. People can only decide how to live with the virus once they know what to expect from their government. Up to now, that has been mainly guesswork.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.