(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Federal Reserve’s stated mandate is to “promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long term interest rates.” The first part is obviously a disaster right now, with more than 36 million Americans filing initial jobless claims in the past eight weeks, bringing U.S. unemployment to levels not seen since the Great Depression. The last objective is easily met, with benchmark Treasury yields hovering close to all-time lows.

But what about stable prices?

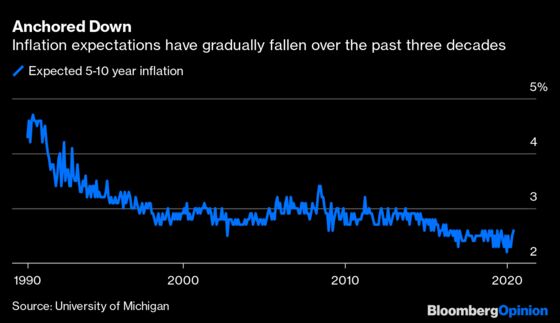

For years, Fed officials fretted that consumers’ inflation outlook was almost too stable at historically low levels. Vice Chair Richard Clarida, for one, follows University of Michigan data that surveys expected price changes during the next five to 10 years. That gauge fell to 2.2% in December, a record low. A year earlier, when it was at 2.6%, he called it “within — but I believe at the lower end of — the range consistent with price stability.” Since 2012, expectations have fluctuated in a tight window of 2.2% to 3%, including 2.6% in a report released Friday. The central bank generally views 2% as its target rate.

The coronavirus pandemic has shaken American households to their core in any number of ways. At best, it’s acclimating to working from home and adjusting day-to-day behavior. At worst, the most economically vulnerable individuals are suddenly unemployed and unsure when — or if — they’ll be rehired.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell previewed some of the devastation earlier this month from what was at the time an unreleased report. “Among people who were working in February, almost 40% of those in households making less than $40,000 a year had lost a job in March,” he said in prepared remarks. “This reversal of economic fortune has caused a level of pain that is hard to capture in words, as lives are upended amid great uncertainty about the future.”

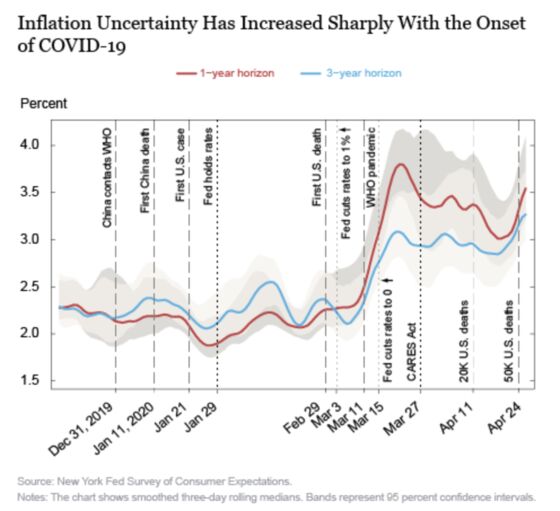

Though seemingly insignificant for now, the once-stable outlook for inflation appears to also have shifted drastically. As America comes out from under the Great Lockdown, how central bank officials handle what could be early signs of unanchored inflation expectations, and how the public responds, could play a crucial role in any recovery.

In a blog post, New York Fed researchers found “unprecedented increases in individual uncertainty — and disagreement across respondents — about future inflation outcomes.” The share of people who expect deflation in 2021 increased from from less than 10% at the end of February to more than 20% a month later. Meanwhile, those who expect short-term inflation to be higher than 4% jumped from about 30% to almost 45% in the same period. In other words, although the median expectation might only show a small move, some households are bracing for a drastic swing.

At a high level, these are two vastly different economic scenarios. Deflation frightens policy makers because rational consumers would postpone purchases to get goods and services at a cheaper price. That would curtail economic activity and potentially exacerbate the situation. Yet much higher inflation would erode the purchasing power of consumers, particularly those with lower incomes or who can’t afford to invest in assets that rise with price growth. Neither of these options is ideal, which is why the Fed is tasked with engineering a stable middle ground.

It’s little surprise that people are so unsure on the direction. On the one hand, an oil futures contract traded at a negative price for the first time, the core consumer price index tumbled month over month by the most on record, and, as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Tim Duy noted last month, there’s growing anecdotal evidence of wage cuts, no matter what the spike in last month’s average hourly earnings figure may suggest. Steven Blitz, chief U.S. economist at TS Lombard, argues that rent, which has been a source of consistent inflation for decades, will experience a drop that will “be bigger and last longer in this cycle.” Add to that a reckoning in higher education, a source of huge cost increases, and the argument starts to form for a deflationary period.

And yet there’s also news about meat-processing disruptions in the U.S. that have cut pork and beef supplies and caused some steak prices to double in the past two months. It’s fair to wonder whether globalization is on the decline and the knock-on effects for the cost of goods. The concern among some inflation-watchers, as Michael Ashton at Enduring Investments LLC put it: “With money supply soaring and supply chains creaking, any return to normal economic activity is going to result in bidding for scarce supplies with plentiful money. You already see that in food, the one thing it’s easy to buy right now. That's the dynamic to fear when we reopen.”

My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Barry Ritholtz wrote earlier that those worried about inflation are probably wrong, just as they were after the 2008 financial crisis. I tend to agree that price growth reaching 5% or higher would require a number of unlikely events to happen concurrently. With data starting to come in from U.S. states that are reopening, it’s becoming clear that a swift return to the pre-coronavirus economy is unlikely.

Surveys are also gloomy. Just 31% of American adults would feel comfortable going to the movies in the next three months, according to responses from May 5-8 from Morning Consult. That’s little changed from 29% in the April 7-9 period. Feelings are about the same for concerts, museums, amusement parks, theater performances and the gym. The latest Small Business Pulse Survey from the Census Bureau showed that almost one-third of respondents expect it will take more than six months to return to normal levels of operation, and 6.2% believe their business will never get back to where it was.

As a general rule, I’d only start to worry about inflation if few others seem concerned about it. It’s worth watching to see if a consensus starts to build in one direction. Admittedly, the idea that price growth was an underappreciated threat was BlackRock Inc.’s rationale for calling it one of the biggest risks in 2020, and obviously that didn’t pan out. Still, after the latest CPI data, Rick Rieder, the company’s chief investment officer of global fixed income, said that “2020’s broad deflationary influences may well lead to higher rates of inflation next year,” adding that the market’s expectations for price growth close to zero are “unrealistic and excessively pessimistic.”

The longer something stays steady, the harder it can be to imagine what could push it outside the norm. That’s especially true for a prominent macroeconomic figure like inflation, watched by traders across markets. American households are signaling they don’t have a clue about what the pandemic will mean for future prices. How it shakes out could have significant consequences for the trajectory of any economic recovery.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.