(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Carnival Corp.’s planned $3 billion bond sale on April 1 is bound to make a fool out of someone. It’s just not clear whether it will be the investors buying the cruise-line operator’s debt or the company.

The case for investors looking foolish: Carnival’s ships are grounded, which of course cuts off its dominant source of revenue. The company’s share price has tumbled from $51 at the start of the year to about $14 as it expects a loss in 2020. Even if it manages to raise $6 billion through bond and stock sales as planned, analysts say that only gives Carnival an 18.5-month liquidity cushion to wait out the coronavirus-induced halt. That’s not much comfort, given that the bonds mature in twice that time and it’s anyone’s guess when — or if — the cruise business returns to normal.

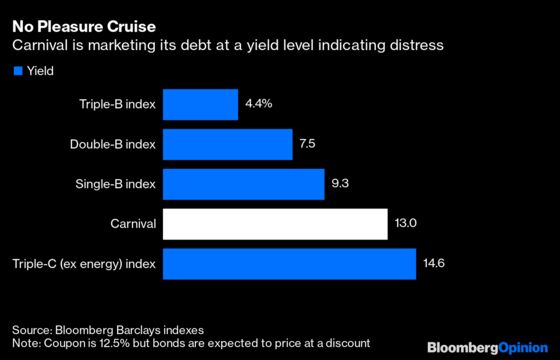

The company, on the other hand, is on the verge of paying vastly more to borrow than its triple-B credit rating would indicate. Bloomberg News reported Tuesday that Carnival’s three-year dollar bonds are being marketed with a 12.5% coupon and most likely will come at a discount, bringing the yield up to 13%. In early February, a triple-C rated company, Husky, issued debt at a similarly high rate. Obviously, it feels as if the entire world has changed since then, but even the average single-B bond yields just 9.35%, and the index never topped 12%, even in the height of the sell-off.

Effectively, Carnival is investment grade in rating only — markets consider it seriously distressed. Bloomberg News even reported that the deal is running off of JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s high-yield syndicate desk, citing people familiar with the matter.

Every once in a while, a single corporate-bond sale takes on outsized meaning about the state-of-play in credit markets and investor sentiment about the outlook going forward. Carnival’s offering will almost certainly be such a deal.

Carnival, quite contrary to its jovial name, made headlines earlier this year because its ships were basically what much of America has now become, only with virtually no refuge. As my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Timothy L. O'Brien reminds us about the Zaandam, a vessel run by Carnival subsidiary Holland America that’s been called a “death ship”:

Although the cruise ship is no stranger to viral outbreaks (two years ago, 73 passengers contracted a norovirus on a trip off the coast of Alaska), the Zaandam and other Holland America and Carnival ships have received high marks in recent sanitation inspections by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet reports have popped up regularly about other Carnival ships that don’t pass muster. (The parent company manages several brands, and the Princess lines have particularly weak health and sanitation records.) So how well prepared was Carnival for something as cataclysmic as the coronavirus?

Moreover, why did the Zaandam set sail on March 7? Well before then, two other Carnival ships had already become poster children for the coronavirus. On Feb. 4, the Diamond Princess was quarantined at a Japanese port after a former passenger tested positive for the virus. A subsequent test administered to that ship’s 3,700 passengers and crew turned up 700 infections; several of those people later died. As early as March 3, it was reported that passengers aboard a Grand Princess cruise in February had tested positive. That Carnival ship, returning from Hawaii, was then detained off the California coast for several days before docking on March 9 to prevent a further spread.

That doesn’t scream a company worth investing in, especially without signs of federal assistance. But notably, bond traders aren’t necessarily banking entirely on a quick rebound in the cruise industry. Carnival’s new notes will be secured by a first-priority claim on its assets, which should provide some ballpark estimates of a worst-case recovery rate. Still, it’s a tough sell to hinge an offering on liquidation value for a company operating in one of the industries facing the greatest amount of uncertainty.

Usually, this is how a deal with such a finger-to-the-wind yield level goes: Investors swarm to the offering and the yield comes down by 50 or 100 basis points, maybe even more. JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Bank of America Corp., which are managing the bond sale, have little incentive to float a coupon rate that was too low to easily clear the market. They want to drum up demand and showcase an oversubscribed order book.

These are not ordinary times, though. While I seriously doubt that Carnival would be willing to pay a yield even higher than 13%, it’s possible that the market just isn’t as receptive to hard-hit businesses as it appears. In that case, the offering could be delayed or downsized a bit. It’s issuing in both dollars and euros, potentially to reach a broader swath of investors and avoid such an outcome.

Unfortunately for Carnival, it needs the cash quickly. That’s hardly an ideal time to be borrowing. And it’s why 13% might be just the right yield for the company and investors alike to let go of their inhibitions.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.