The 52% Shortfall in Britain's Coronavirus Count

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- How many people in the U.K. have died from the coronavirus? It’s a bleak question with many answers — too many, considering the importance of this number for an anxious public, for politicians trying to craft a strategy and for financial markets seeking guidance.

The U.K.’s official daily Covid-19 death count was 12,868 as of April 14, which on the surface would suggest a more benign outbreak than in Italy, Spain, France or the U.S. But this is a number with a big problem: It only counts deaths in hospitals of people who tested positive for the virus. It fails to capture other sources, such as deaths in nursing homes, where elderly residents are particularly vulnerable and where staff lack adequate equipment.

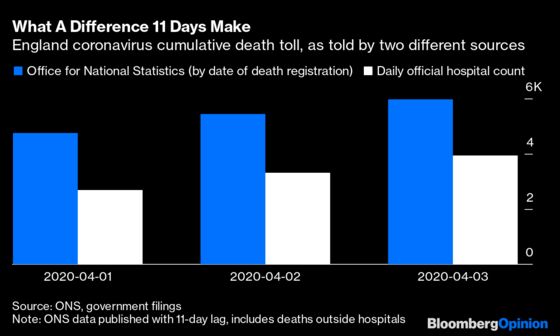

Another way to try to capture the size of the virus crisis is to look at all death certificates, and tally up those that mention Covid-19. That data is compiled by the Office for National Statistics and it gives a more complete picture, albeit with an 11-day publication lag. The latest snapshot, covering the period through April 3, shows 5,979 coronavirus deaths registered in England, the part of the U.K. with the heaviest toll. By contrast, using the official daily hospital count, England’s deaths as of that date totaled 3,939. That’s a gap of 2,040, or 51.8%. The difference had been even wider, at more than 60%, earlier in the month.

Now there are worries that even death certificates aren’t capturing the scale of the human tragedy unfolding in care homes. A lack of testing means cases might be going unreported, and the strain on the system may be leading to errors: A whistleblower this week told Channel 4 News that some doctors simply weren’t registering suspected coronavirus deaths. Care homes are starting to try to fill the information vacuum themselves, with media on Wednesday reporting industry estimates of 1,400 deaths in England. That’s far higher than the 217 nursing-home deaths recorded by Office of National Statistics up to April 3.

Given the issues of credibility and public confidence that are at stake, especially considering Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s recent brush with the virus, there is an obvious incentive for the British government to make an effort to include nursing-home data in the daily count — which is what care organizations explicitly want. Yet that still hasn’t happened. The challenge, apparently, is balancing speed with rigor. “We just need to be absolutely clear that the cause of death that is attributed is correct and that is what takes time on the death certificate to get right,” explained one official recently.

Is this such a hard trade-off? Other countries have managed it. Germany reports all deaths that tested positive for coronavirus on a daily basis, as does Ireland. Undercounting is still a risk everywhere, but the obvious vulnerability of nursing homes has become impossible to ignore. France, which initially had the same methodology as the U.K., changed its daily count on April 2 to include care homes — and it doesn’t require that every person be tested in order to be included in the statistics. This has had a big impact on France’s numbers, with nursing homes accounting for 38% of total deaths, but the benefits of transparency are worth the cost of an optical bump in fatalities.

Even as it keeps to its own statistical path, the British government is happy to compare itself with its European neighbors, while studiously avoiding any discussion of methodology. When Health Secretary Matt Hancock recently compared the U.K. death rate with Italy’s and Spain’s, he said Britain’s count had been inflated by its larger population. Johnson’s Twitter account regularly publishes a “global death comparison” chart directly comparing Britain’s hospital tally with counts from countries such as France that are more complete. Yet if France actually used the same methodology as the U.K., the number of its deaths would suddenly shrink to 10,643, from 17,167. Imagine the outcry.

This isn’t just an issue of bad data, even if the coronavirus crisis has more than its fair share of that. It’s also about the human cost of “airbrushing” deaths. It’s an emotional subject for relatives forced to be apart from their loved ones even as they die, and a source of general anxiety for people asked to give up their freedom to fight an invisible enemy and save lives. If the information governments feed their citizens on a daily basis becomes a source of distrust, there will be repercussions down the road. The U.K. should proactively ensure that doesn’t happen.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Brussels. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.