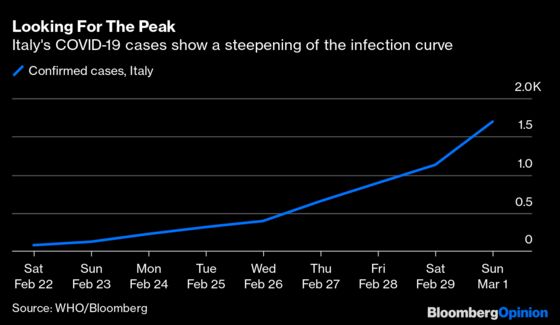

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The daily counting of new coronavirus cases has become a grim fixture for politicians, investors and the public. The latest figures suggest the infection is past its peak in China, where cases appear to have plateaued. But it’s spreading fast elsewhere. Italy, which emerged as the epicenter of the virus in Europe last month, posted a 50% jump in confirmed cases on Sunday to 1,694 — more than any other country bar China and South Korea — while France’s rose 30% to 130. Swathes of Northern Italy are in lockdown, while France has banned big public gatherings and advised against la bise.

But this critical indicator is starting to look pretty vulnerable to changing testing methods and the nudging of politicians.

In Italy, the government is starting to wonder how much of the country’s case increase is due to potentially over-zealous testing. Italy has tested more than 10,000 people so far, including people with no actual symptoms. That’s about 10 times more than in neighboring France, where the criteria for testing cases is much stricter. Italy is also officially reporting data from local regions before full confirmation from central authorities. This all looks too hasty, and even harmful with “too much testing,” according to Walter Ricciardi, a World Health Organization official and adviser to the Italian government. Carriers of Covid-19 who are asymptomatic might recover on their own — and Rome no longer wants them on the books. From now on tests will only be conducted on people with symptoms, in a bid to contain what the government calls a media “infodemic” that’s hurting Italy.

It may seem odd to want to test less — the more we know about a disease, the better — but the Italians have a point. Testing resources are by definition scarce, and some kind of prioritization makes sense to try to separate genuine “super-spreaders” from “super-worriers” who clog up waiting-rooms. Clearly, when dealing with a disease that has a stealthy incubation period around two weeks, being asymptomatic is no guarantee against infection. Still, the WHO in February advised that people with symptoms “spread the virus more readily through coughing and sneezing” than those with none.

The challenge when politicians start to intervene in data collection of this kind is keeping public trust intact. If Italy’s rate of new cases starts to fall, will that be seen as a result of epidemiology, or new methodology? In France, where there’s a strict lid on testing, people with symptoms who aren’t eligible for tests (because they haven’t traveled to places like China) are openly questioning whether the restrictions are designed to keep case numbers down. The Louvre Museum’s closure this weekend happened on the demands of its employees, not its management. Clear communication is vital.

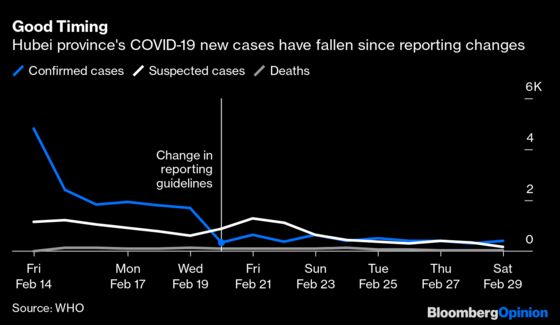

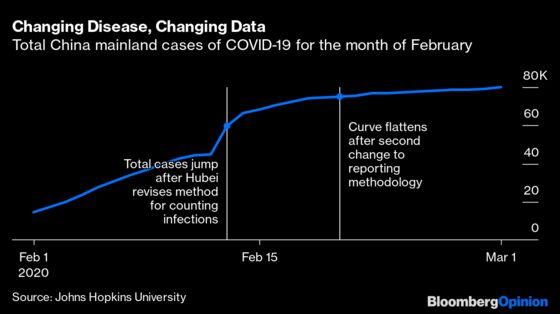

This is made harder when testing methods change dramatically, as has been seen in China. The chart below shows the daily change in COVID-19 cases reported by Hubei province, widely acknowledged as the original epicenter of the outbreak. The declining rate of cases is part of what the WHO has described as post-peak virus behavior, suggesting the worst is over after tough quarantine measures. But it also coincides with a change in national state guidelines on Feb. 20 asking for a simplified case count.

That change was the second in a month for China. On Feb. 13, COVID-19 cases in Hubei province surged 45% to almost 50,000 after a revision in reporting methods. A decision was made to do more clinical diagnosis via lung scan, rather than just via specialized laboratory test kits. The measure was praised by experts as a way to respond to a lack of testing capacity. But the subsequent switch on Feb. 20 has left some wondering how much of the ebb and flow of the epidemiological curve is really about the disease, or promoting a narrative that it’s being successfully controlled. (China has in the past admitted to underreporting data, such as during the SARS outbreak in 2003.)

Epidemiologists are used to statistical noise. Professor Jennifer Nuzzo, of Johns Hopkins University, says that while the methodology changes in China have been puzzling, much can be deduced from the virus’s geographic spread, speed of transmission and severity of symptoms. Paradoxically, an underreporting in cases can be a good thing, as it suggests the true mortality rate — deaths as a proportion of total infections — is lower than the current estimated level of 2%.

But the more governments give the impression of seeking to nudge the infection curve, the likelier people will turn to other sources. That’s already happening in China: The firm RS Metrics is using satellite imagery to monitor the gradual return to normality for industrial activity in Hubei, while travel agency Tongcheng-Elong Holdings Ltd. is pointing to a rise in flight searches on its platform for the holiday season as an optimistic sign the worst is over. Maybe it is. But even in our numbers-driven world, it looks like the COVID-19 infection curve is serving up confusion as much as clarity.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Brussels. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.