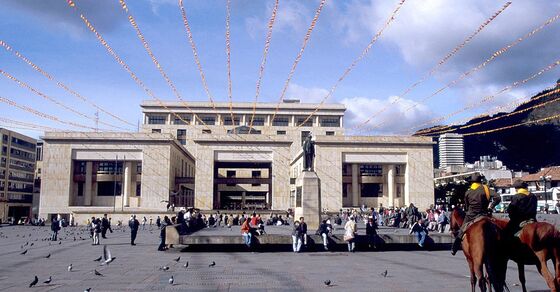

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There is perhaps no greater success story in the world over the last three decades than Colombia. To see this, just stand in the middle of the Plaza de Bolivar in the center of Bogota.

In 1988, when I first visited the country, there was a gaping hole along one entire side of the square. That was where the Palace of Justice had been, before guerrillas entered, killed some supreme court justices and took other hostages, prompting a confrontation with the army that left about a hundred dead and the building a smoking wreck. Traffic was acutely congested, in part because traffic lights were smashed so that fragments of green glass could be sold as emeralds. Much of Colombia’s territory was in the control of either guerrillas or paramilitaries, fueled by all-powerful drug cartels. Violence was endemic.

Returning to the square last month, I found a new and elegant Supreme Court building where that wreckage had once been, part of an ambitious urban regeneration that has created a vibrant cultural quarter. Other changes: Traffic moves smoothly — at least by the standards of a large Latin American city — through green streets, and Bogota is at last about to build a metro (the second city Medellin, once notorious for the drugs trade, already has one, built as part of an even more remarkable renaissance). The new rapid-transit line will transport a growing middle class accustomed to much the same standards of living that people expect in North America into a downtown of glistening and modernistic skyscrapers.

The changes are the outward signs of a remarkable transformation. Colombia is now established as a middle-income country, growing faster than any other major economy in Latin America. With a population a bit larger than Spain’s, it also is now South America’s second-biggest economy, blessed with relatively stable politics, natural resources, proximity to the U.S., and a Pacific coast which eases trade with Asia. The currency is stable. And while the three zeros at the end of all the nation’s banknotes are a reminder of serious inflation in the past, it has never lapsed into hyper-inflation, and — alone among major Latin American economies — has never defaulted since the second world war. Most important, the savage war that dragged on for decades, one of the bloodiest that the Western Hemisphere has ever witnessed, appears at last to be winding down. The largest guerrilla group has handed in its weapons, and an uneasy peace is holding in much of the country. The homicide rate is less than half its horrific level when I last visited. And Colombians can begin to enjoy themselves. Thirty years ago, the most famous Colombian was Pablo Escobar; now that title belongs to Shakira.

Having come so far, however, Colombia is finding it hard to proceed much further. It wouldn’t be the first country to fall into the “middle-income trap,” and it is dogged by the familiar problems of Latin America, as well as lingering issues from its own troubled past. It is deeply unequal. Rural Colombia, which bore the brunt of the violence, remains untouched by the improvements that have blessed the cities. Cocaine production is higher than ever. And while an influx of refugees from the economic disaster in neighboring Venezuela has stimulated the economy, it is also destabilizing and increases social tensions.

The last few months in particular have seen street protests against the deeply unpopular right-wing president Ivan Duque. Those demonstrations have been mild in comparison with Chile, the far more prosperous and formerly politically stable nation to the south. But they share a common cause which has alarmed Colombia’s political elite. Namely, there are grave doubts over whether the carefully constructed but unduly complicated pension system will actually deliver a secure retirement. Pensions aren’t growing sufficiently, and don’t cover enough people. This highlights another obstacle to Colombia’s development.

With political stability and the rule of law now largely in place, Colombia should have all the preconditions to create the deep capital markets that can fund further growth. But in practice, those markets aren’t growing, and it is hard to see how they can. Only about six large companies trade with significant regular volume on Bogota’s stock exchange. There are just four private pension funds, dominated by two. They hold sway over Colombian stocks, and tend to buy and hold, limiting liquidity still further. The IPO market is moribund, leaving wealthy Colombians who have built a business with little or no incentive to take it public. The debt market is more active, but dominated by a few big issuers with strong credit ratings who tend to crowd out smaller, more entrepreneurial borrowers.

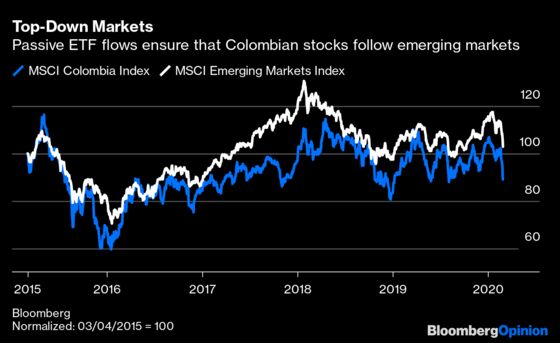

If that weren’t enough, the way international finance now operates has created extra barriers to development. Most money for Colombian equities is invested through passive exchange-traded funds, which mostly track indexes of emerging markets as a whole, or Latin America. Thus demand for Colombian equity often depends on events in Brazil or Mexico — or even China. The ETFs in practice simply hold two or three Colombian stocks, and buy or sell them occasionally in response to changes in sentiment toward the region as a whole — and every gyration in MSCI’s emerging markets index is immediately matched by a move in the Colombian index.

While equity finance is dominated by index-providers’ decisions, debt is driven by credit-rating companies. Colombia is now an investment-grade country, a remarkable achievement given its recent history. But it is only just into investment-grade territory. A downgrade by any of the three main rating agencies could force highly regulated overseas pension funds to drop their Colombian bonds.

Despite its achievements, then, Colombia still lacks the conditions to create powerful capital markets, while modern finance is structured in such a way as to make international capital excruciatingly hard to come by. And so as much as Colombia is a success story — and it is — it is also a vivid illustration that the division between governments and markets is a false dichotomy. Building a stable and growing economy with strong institutions won’t cause markets to take root on their own. That requires difficult reforms at home, and a profound re-think of the way the developed world does its international investing.

As it stands, an obvious compelling investment opportunity is going begging. At one level, that missed opportunity jeopardizes the stability of an increasingly important strategic partner to the U.S., which provides a crucial pressure valve for the instability in Venezuela. At a human level, it brings the likelihood of yet more avoidable misery for a population that has suffered too much already.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.