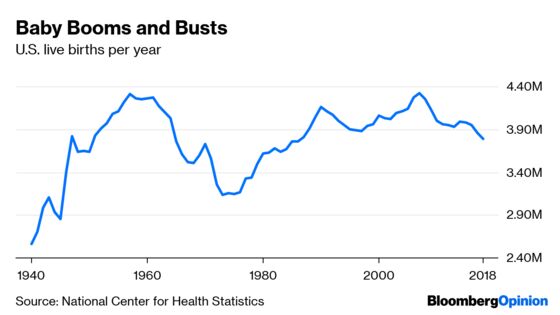

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The decline in births that began in the U.S. in 2008 has already been long and deep enough that it’s going to shape the country’s future in a big way.

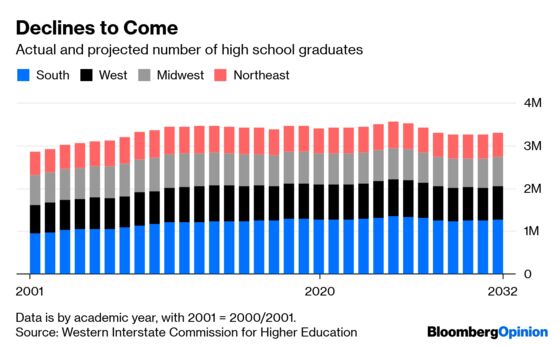

This drop is not nearly as sharp or as deep (yet) as the one that followed the baby boom of the late 1940s to early 1960s. But it will change things, and the changes will become apparent first at educational institutions. The number of public-school kindergartners in the U.S. began falling in 2014, and that decline — offset modestly by immigration — will continue to work its way through the K-12 system in the coming years. By the second half of the 2020s, colleges and universities should start feeling it.

These looming declines have already occasioned much discussion and concern in higher-education circles. Still, forecasts based on demographics don’t always pan out. The even-sharper birth declines of the 1960s and 1970s led not to the college enrollment bust that many had feared but to moderate increases as enrollment rates leaped higher, spurred in part by a rising wage premium for college graduates. In 1980, 49% of high school graduates went directly to college; by 1997, the rate was 67% — about where it is now. Then, in 1989, economist and former Princeton University President William G. Bowen published a now-infamous forecast that rising enrollments due to the big rebound in births in the 1980s would along with several other factors result in “substantial excess demand for faculty,” especially in the humanities and social sciences, starting in the late 1990s. Bowen and co-author Julie Ann Sosa were right that post-secondary enrollment would rise: It went up 45% from 1997 to 2011. What they didn’t foresee was that colleges and universities would react by shifting much of the teaching burden onto a new underclass of adjunct professors, some of whom had been lured into academia by the promise of the Bowen report.

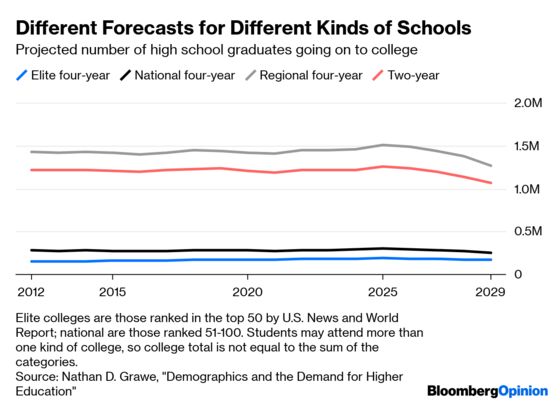

Nathan D. Grawe, an economics professor at Carleton College in Minnesota, doesn’t want anything like that on his conscience. “The late 2020s look to be a very poor time to be seeking a teaching post in higher education,” he warns in his book “Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education.” He also suggests that pressure to get rid of faculty tenure protections will intensify in the 2020s. But most of the book (and the accompanying available-to-all dataset) are devoted not to such pronouncements but to a wonderfully transparent exploration of what we do and don’t know about the likely college students of the 2020s. It was published early in 2018, but I only found out about it a couple of weeks ago; the demographic trends haven’t shifted much since 2018 and I think Grawe’s projections deserve more attention than they’ve gotten. So here goes:

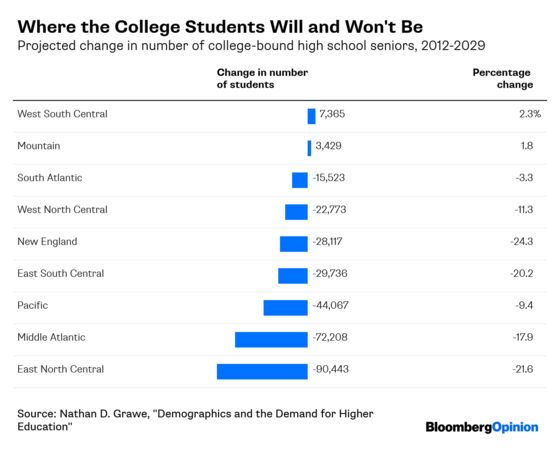

Even amid a forecast of big national declines in the number of college-bound students, some parts of the country should see increases. Grawe bases this not just on raw population numbers but on what he dubs the Higher Education Demand Index, which he constructed mainly by taking demographic data from the 2011 American Community Survey conducted by the Census Bureau and then using National Center for Education Statistics’ 2002 Education Longitudinal Study, which has followed a group of students who were high school sophomores in 2002 and seniors in 2004, to estimate the likelihood that students from different backgrounds will attend college, and what kind of college.

Among other things, this approach paints a very different future for elite colleges than for community colleges. All can expect enrollment declines in the late 2020s, but the elite schools (the top 50 in the U.S. News and World Report rankings) will probably have more potential students than they do now, while the national ones (the next 50) will see only modest declines. So it looks like it won’t get any easier to get into Harvard. Sorry, kids! Meanwhile, the nation’s two-year colleges are facing a potential 13% decline in demand from the 2012 baseline, and those in the hardest-hit census subregion, the East South Central (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee), face a 29% decline.

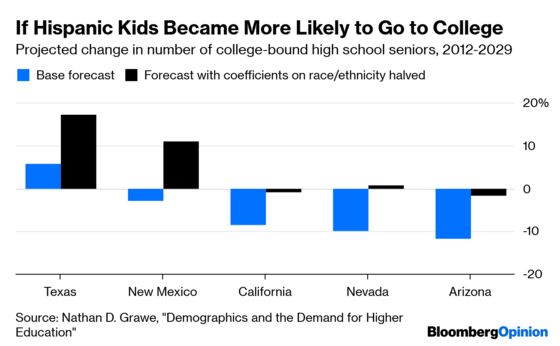

Despite all this, the overall college enrollment rate, which has actually slipped a little over the past decade, is not forecast to rise in the 2020s. The main reason: A growing percentage of high-school graduates will be Hispanic, and in the 2002 longitudinal survey that informs Grawe’s forecasts, Hispanic kids were much less likely to attend college than others, all else being equal. This could change, so Grawe also generated alternative forecasts in which Hispanics and other racial and ethnic groups made up half of their projected gap in college enrollment rates relative to Asian Americans, the group with the highest enrollment rate. That had some pretty dramatic effects on the forecasts for the five states where Hispanics make up the highest share of the population.

Grawe also generated forecasts in which the effect of parental incomes was halved, with similarly salutary results. Demographics doesn’t have to be destiny here — in the 1980s, remember, a big rise in college enrollment rates offset a big decline in the college-age population. A full repeat of that is unlikely, but this does seem like a moment when leaders of community colleges and regional four-year schools in particular should be exploring all possible ways to make their offerings more relevant and affordable for those on the fence between attending college or not.

Another priority should be keeping those already in college from dropping out. In a remarkable interactive graphic, David Leonhardt and Sahil Chinoy of the New York Times showed how widely current graduation rates vary even among colleges with similar student populations. Grawe sort of wishes he’d made this a theme of his books, too. “Higher retention is obviously helpful as institutions wrestle with their budgets,” he emailed, “but it also serves higher education’s mission to enable student success and to train the next generation of skilled workers required by industry.”

In the not-too-distant past, the U.S. higher education system faced a flood of new students, and didn’t handle it particularly well — especially after state and local governments slashed funding in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. As has been the case in so many ways: Tough luck for the millennials. The forecast enrollment drought to come, then, might at least be a chance to do right by a new generation.

With whom I worked on Princeton's college newspaper. She at least did end up in a tenured academic job, albeit not in the humanities or social sciences but in medicine.

The areas in the chart are census divisions. If you're curious which states belong to which divisions, here's a map.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.