CLOs Cracked Like No Other Credit Market. So Now What?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Investors and strategists in the bond markets rarely, if ever, come out firmly against their own asset class. Rather, they opt to use language like “be selective,” “move up in credit quality” or “clean up portfolios.”

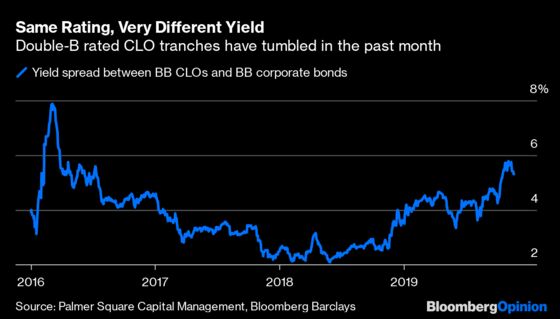

This is what’s happening now in the once red-hot market for collateralized loan obligations. In October, while U.S. stocks soared to records and high-yield bonds posted their fifth consecutive monthly gain, the pools of leveraged loans quietly faced something of a reckoning. Prices on double-B CLOs tumbled to the lowest in more than three years, according to data from Palmer Square Capital Management. In the span of about six weeks, their yields shot higher by 110 basis points while those on double-B corporate bonds dropped by 43 basis points, creating the widest spread between the two similarly rated assets since March 2016. Double-B leveraged loans themselves barely budged.

At first glance, this would seem to be an obvious buying opportunity. A double-B rating is below investment grade but doesn’t signal inevitable distress, after all. Of course, there’s a catch — and it’s a big one. The same capital structure that has long been cited as an appealing attribute of CLOs is now seen as a looming hazard for investors. The weakest leveraged loans are looking more vulnerable to default. If enough did so, that would threaten portions of the CLO debt stack, often starting with the double-B segment.

“Loans, as a whole, absorbed much of the public market lending excesses in recent years,” Citigroup Inc. strategists led by Michael Anderson wrote in a Nov. 15 report. “Loans financed over the past few years during extremely loose lending standards are beginning to season and reveal fundamental cracks. We expect that trend to continue. Consequently, we recommend investors focus on clean portfolios from stronger managers.”

Morgan Stanley, in a Nov. 19 report, drew a similar conclusion. “Our Leveraged Finance Strategy team is calling for leveraged loan defaults to double next year and for downgrade pressures to continue. Higher default rates will likely be accompanied by lower recoveries resulting from an increase in loan-only structures and weakening covenant quality.” In the bank’s base-case scenario for 2020, top-rated CLOs will outperform double-B rated debt.

There’s still a ways to go before those who have long predicted doom for CLOs are proved right. In many ways, this is all just another side of the consensus story in credit markets. The lowest-rated corporate debt has stumbled in 2019 as investors increasingly fret that slowing global growth will spell trouble for teetering companies. If a larger number of weak leveraged loans fail to pay, that would first choke off payments to holders of CLO equity, followed by the single-B CLO tranche (if there is one), then the double-B tranche, and so on.

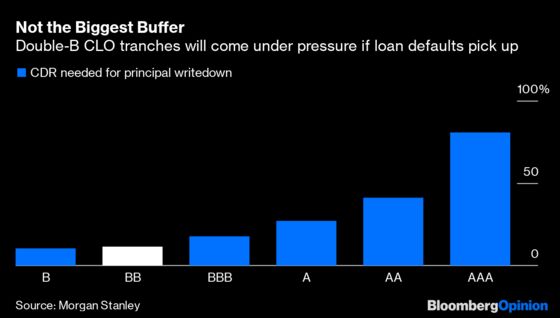

The pressing question for CLO investors is the magnitude of any shakeout. By Morgan Stanley’s calculations, it would take a so-called constant default rate within the pool of 11.5% over the life of the deal for the double-B tranche to take a principal writedown. By contrast, it would take a whopping 80.8% default rate for top-rated CLOs to take a hit. That huge buffer is why they famously never defaulted, even during the financial crisis.

I hesitate to draw parallels between weak leveraged loan covenants and poor underwriting standards for subprime mortgages in the mid-2000s because calling CLOs the next CDOs is too neat a comparison and unlikely to play out in reality. And CLOs are certainly nothing like the toxic “CDO-squared” structures, which created all sorts of now-obvious contagion risks. Plus, financial regulators are well aware of the boom in leveraged lending, and everyone from the Financial Stability Board to the International Monetary Fund to the Bank for International Settlements has said they’re monitoring the risks. If loan defaults start to pile up, few can feign ignorance.

However, subprime mortgage default rates are a stark reminder of what a true worst-case scenario looks like. According to a 2010 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 23.4% of subprime mortgage loans originated in 2004 defaulted within the first 21 months. That figure jumped to 31.7% for 2005 and 43.8% for 2006 before coming down to 32.2% for 2007.

Unless the U.S. falls into a deep and long-lasting recession, it seems highly unlikely that leveraged loans could even come close to reaching such lofty default figures. I buy the argument that the corporate debt is less concentrated in one specific area and therefore less prone to widespread collapse. And there’s obviously a difference between weaker loan covenants and some of the outright fraud perpetuated during the subprime crisis.

And yet a low-double-digit default rate doesn’t feel impossible, which helps explain the sell-off in double-B CLOs. Fitch Ratings said in a note this month that loans on its troubled-loan watchlist made up 6.2% of the overall CLO portfolio at the end of the third quarter, up from less than 5% three months earlier. In at least some pockets of the leveraged-loan market, things are starting to become dicey.

Morgan Stanley’s report makes clear what’s at stake for investors in the coming year. The bank’s base case calls for a modest 0.75% excess return in 2020 for double-B CLOs. However, its bullish case sees a 25.75% gain for the debt, while the bearish case would produce a 9.25% loss. That’s a wide range of outcomes. “If sentiment on corporate credit materially improves, we think high-beta CLO BBs offer more upside than any other investment in the securitized products space,” the strategists wrote.

Is that a risk worth taking? Judging by last week, at least some investors are betting the sell-off went too far, with the yield on double-B CLOs falling by the most since May.

But nothing has changed fundamentally as of late. Bond investors are still shying away from the riskiest credits, even with the widest spreads in 11 months. The economic outlook calls for slow, unspectacular growth, and news that “phase one” of a U.S.-China trade deal could be pushed off until next year doesn’t help matters. It’s not exactly a robust environment for shaky companies.

So in that sense, it’s understandable why CLO investors are getting picky. It’s not time to bail on the structures entirely, but seeking higher ground might not be such a bad idea when the potential wave of defaults is just starting to form.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.