(Bloomberg Opinion) -- More than a decade after Lloyd Blankfein, then-boss of Goldman Sachs Group Inc., claimed banks do “god’s work,” the finance industry still struggles to convince the public it’s a force for good.

A new chapter in this debate has erupted in Europe where hedge funds and national governments can’t agree on what constitutes “good” financial speculation.

Funds who bet that the price of emission permits would soar in Europe’s carbon market, the world’s largest, say they’re forcing polluters to decarbonize, thereby helping the planet. “Greed can be a wonderful thing when it works for the benefit of the environment,” Ulf Ek, founder of hedge fund Northlander Commodity Advisors told Bloomberg Markets in August.

Indeed, carbon is one of the world’s best performing commodities this year. EUAs (European carbon permits) have outperformed even bitcoin since January. The price has increased almost five-fold since a low in March 2020. On Monday, carbon for December delivery hit a record of more than 75 euros ($85) per ton.

Betting that pollution becomes more expensive is more socially acceptable than that other popular hedge fund strategy of scooping up unloved oil and gas stocks. Yet at a time when consumer electricity bills are rising and businesses are struggling with higher energy and carbon compliance costs, hedge fund windfall profits are politically incendiary. Why should they benefit from industrial companies and utilities that must actually hold and trade the permits to cover their pollution?

Calls for intervention to stem the influence of speculative traders in Europe’s carbon market have grown louder. Coal-reliant Poland reiterated last week that speculation must be curbed, while Spain warned in September that “a bubble on EU ETS is the last thing we need.” Denmark and the Czech Republic have made similar complaints in recent months, as have industry players.

The purpose of Europe’s carbon market “should be to combat climate change at the lowest possible cost instead of being a casino for hedge funds where a transfer of wealth from end-consumers to hedge funds is taking place,” Stromio GmbH, a German electricity supplier, warned in September.

Of course, there’s a long history of bashing financial speculators in Europe, and there’s no consensus about what, if anything, to do about it. The European Commission appears to want high carbon prices, as does Germany, where the new coalition government is considering a national carbon price floor.

But it’s unfair to single out hedge funds because so-called compliance entities — companies like utilities that are required to obtain permits for their emissions — also have big carbon trading desks. Plus, “speculators” pursue a variety of strategies: Some might use leverage and trade short-term while others have a multi-year buy-and-hold approach.

Recent fluctuations are certainly worth keeping an eye on — the price has surged more than one third since mid-October. “Industry can work with a high and stable carbon price, but excessive volatility caused by short-term speculation is potentially toxic as it clouds (carbon-abatement) investment decisions,” Jan Ahrens, head of research at SparkChange, a recently launched carbon exchange-traded commodity (ETC), told me.

However, Europe should resist tampering too much with a market that’s finally working as it’s broadly supposed to. The presence of financial investors helps ensure the market is sufficiently deep and liquid, notes BloombergNEF’s European carbon analyst Bo Qin. Ultimately, higher prices reflect how the continent is finally getting serious about cutting emissions: Europe has committed to slashing carbon pollution by at least 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels, and more industry sectors will have to buy carbon permits.

“The carbon market needs more capital to be employed in order to better reflect the true societal cost of emissions. The only way to attract large scale institutional money is by providing a market that gives the opportunity for profits, and we think that opportunity is there now,” Northlander’s Ek told me.

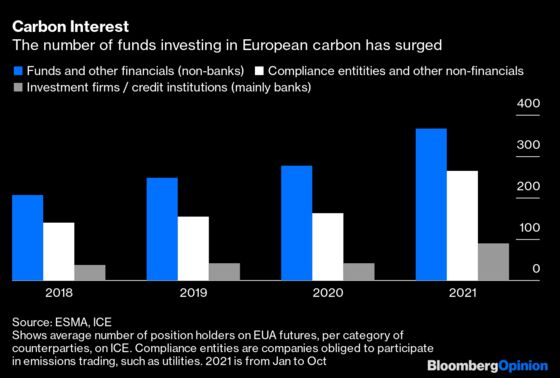

There’s no question Europe’s carbon market has suddenly become very interesting to hedge funds and the big commodity trading houses, as well as an increasing number of exchange-traded funds and ETCs that allow regular investors to gain exposure to the market.

After years of stagnation and low prices, the carbon market began taking off in 2018, thanks to reforms to mop up a huge oversupply of permits. Hedging by utilities and others has soaked up further excess supply — German power company RWE AG says it’s financially hedged out to 2030 — meaning the market has become much tighter. Some companies may also be hoarding permits in anticipation that prices might rise further.

The latest price rise, for example, has been triggered by soaring gas prices that temporarily encouraged utilities to burn more coal (for which they need to hold more pollution permits).

Although the number of funds active in the futures market has increased, they account for less than 10% of open positions in EUA futures. Earlier this month, a preliminary report from the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), commissioned at the behest of several concerned governments, attributed rising carbon prices to economic fundamentals and political decisions. It found no evidence of foul play by traders. A more in-depth study is pending.

“We’ve seen for a while now that this market doesn’t have an easy time finding an equilibrium when things get really tight. Those with a surplus just don’t want to sell,” says Trevor Sikorski, head of gas and carbon research at consultancy Energy Aspects.

“Prices are supported by fundamentals and therefore would have risen anyway, but there’s no question hedge funds add additional demand to the market,” says Bostjan Kovacevic, a trader at Belektron. “If a big player comes with plenty of cash it can disrupt market prices quite heavily in the short term.”

However, carbon needs to remain a credible market and hence any adjustments mustn’t be too heavy handed. Higher prices cause pain for some and result in windfalls for those who correctly forecast them, but that’s just how markets work. In the long run, higher carbon prices are exactly what’s needed to decarbonize industry and tackle the climate crisis.

This figure doesn’t include options. the annual double-sided value of trading in emission allowances and derivatives thereof was 687 billion euros, according to ESMA

Such options have embedded leverage, allowing speculators to stake a comparatively small amount of capital and obtain a potentially large holding.

The same is true of holders of call options who may buy the underlying allowances to drive the price closer to where the options are in the money

The EU can intervene if for more than six months the price is more than three times the average price of allowances during the two preceding years. It would then have to consider if the price is driven by fundamentals or speculation

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.