Climate Change Is Happening. We’ve Got to Pay More to Adapt.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Global warming is here and the world is not ready.

The need to adapt to a transforming climate used to be seen as a distraction from the more urgent goal of preventing change. Today, it’s clear adaptation can no longer wait. Floods, droughts, severe hurricanes and a heat dome in the Pacific Northwest this year alone have been a reminder that reality is already expensive and unpredictable, and getting more so. Both mitigation and preparation require attention to avoid increased hunger, insecurity and mass migration.

A United Nations report released last week during the Glasgow climate talks said adaptation costs in developing countries were now five to 10 times greater than the current amount of public finance being invested. The gap is widening as costs rise, and could hit as much as $500 billion a year by 2050 for those same emerging economies, facing the greatest burden relative to their resources. It’s climate justice at its most basic.

So why are we not investing more to help the whole world to cope?

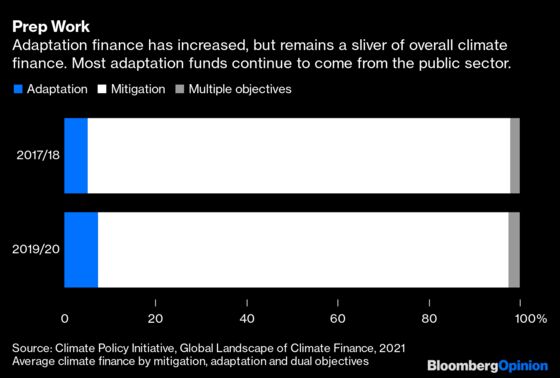

Accord to the Heinrich Böll Foundation, out of $3.4 billion in spending approved last year by major multilateral climate funds and spent across 151 countries, $1.6 billion went to mitigation projects and just under $900 million spent on projects that tackled both mitigation and adaptation. Less than $600 million was approved for adaptation projects alone. Or consider the funds promised by the rich world to developing nations: Not only is the figure falling short of the $100 billion-a-year target, but only a quarter went specifically towards adaptation. Too much of that, meanwhile, is still provided as loans, which indebted countries can ill-afford. Preparation makes up an even smaller percentage of overall global climate finance.

Clearly, the best way to deal with heavier rainfall and rising sea levels is to decarbonize and avoid these outcomes altogether. But even under an optimistic scenario where net-zero emissions are reached by around 2050, we can expect significant changes, and the countries least equipped to deal with the consequences — from sub-Saharan Africa to Pacific islands — will suffer most severely. Some of the damage, and this new uncertain existence, is now locked in. It’s true that the International Energy Agency, which before Glasgow had put the world on track for 2.1 °C of warming, has now said increased pledges around the summit could reduce that to 1.8 °C. But that’s dependent on promises — and is still a temperature level that brings major climate risks.

There have been improvements. The United Nations says close to 80% of countries have embraced at least one national-level adaptation planning instrument, whether it’s a strategy or a law. But climate change is outpacing preparation, funding is insufficient and data on both risks and plans is incomplete. Covid-19 was a missed opportunity, with only a fraction of the trillions spent in fiscal stimulus globally going towards adaptation.

The fundamental problem here is an obvious one. Mitigation projects, whether it’s solar panels or electric buses, have a longer track record, are often larger and easier to fund with loans provided by multilateral institutions or commercial funds. Adaptation, by contrast, tends to involve smaller projects, a perception of low or no returns and the greatest need is in developing nations with more limited capacity to attract the necessary cash. So what can be done?

First, we need to understand that adaptation is a cross-border issue, not a domestic one, as Georgia Savvidou at the Stockholm Environment Institute, who contributed to this year’s UN Adaptation Gap report, explains. The Paris Agreement adopted in 2015 recognizes this. Set against mitigation, drought-resilience in sub-Saharan Africa or protection from rising sea levels in Palau may be seen as a local problem — and yet the knock-on effects from climate-induced crop failures, shortages and population movements will indisputably touch everyone.

Then, we must acknowledge that private capital is essential. Commercial investors are already increasing their currently paltry adaptation role as geospatial technology and climate insurance attract attention — but they remain far less interested in the poorest nations. That means development banks and bilateral donors need to up their game, de-risking projects — the cost of capital rises with climate challenges — with guarantees or first-loss capital.

They can provide technical assistance to help make adaptation-focused projects attractive, even simply by packaging several together, and they can help governments overcome capacity limits. Savvidou and researchers at the Stockholm Environment Institute and University of Cape Town studying climate finance in Africa between 2014 and 2018 found that disbursement ratios for adaptation funds — the amount actually paid out — was less than 50%, compared with nearly 96% for development finance overall.

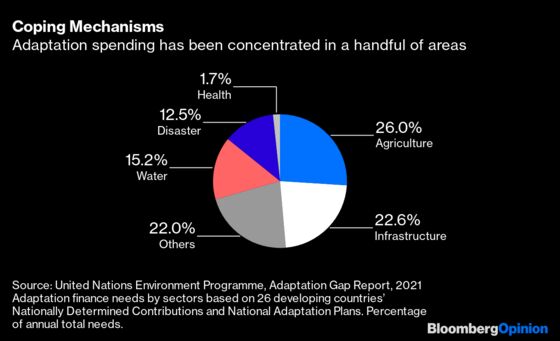

But it’s also true that not all projects will be bankable in the same way. Agricultural projects might be, but not restoring coastline vegetation — even if such adaptation projects often have mitigation benefits too. That requires a significant increase in grants, which added up to just over a quarter of overall public climate finance in 2019, according to the OECD. Debt reduces the fiscal space to cope; grants tend to be more easily disbursed, reaching the least developed. Using climate funds more effectively will help with that too.

Finally, there’s a need to define adaptation more clearly, and to take a wider view. The lion’s share of funds today are allocated to a handful of areas like water and agriculture, but overlooks vital climate-change basics like health or education. A healthier, educated population is more resilient. More attention needs to be paid to multipliers too, like ensuring women play a role in every project.

Climate catastrophes are here. Prevention is overdue.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.