(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Countries and companies across the globe are finally getting serious about climate change. For Latin America, this quickening green transition could attract hundreds of billions in investment, help spur an economic recovery and let nations leapfrog technologically. What’s needed is a policy U-turn, particularly in Brazil and Mexico, its two biggest economies. If their leaders don’t get out of their own way, the region will be left behind.

Dozens of nations have shored up commitments to slow rising temperatures in the run-up to November’s next United Nations climate change conference, COP26, in Glasgow. Europe and the U.S. have pledged to halve or more their emissions over the next decade. Emerging economies have promised to trim future emissions and step up adaptation by redesigning cities and rethinking agricultural practices.

The public spending needed to fulfill these commitments is on the rise, as the EU, U.S. and China put up money for more solar plants and wind turbines, electric charging stations and energy efficient buildings. Globally, tax breaks for coal and other fossil fuels are winding down while support for carbon border adjustment taxes grows.

Companies are getting into the act. Microsoft Corp. plans to remove more carbon than it emits every year; Walmart Inc., pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca Plc, France’s TotalEnergies SE, and Mastercard are among the many already working toward net zero emissions over the next couple of decades. Laggards face the threat of shareholder revolts: Exxon Mobil Corp.’s recent travails with hedge fund Engine No. 1 point toward more high-profile board shakeups by climate activists. ESG funds are some of the fastest growing pots of money around, already totaling some $1.7 trillion. BlackRock Inc. and other big investment players plan to favor environmentally friendly firms in their everyday portfolios, bringing trillions more into play.

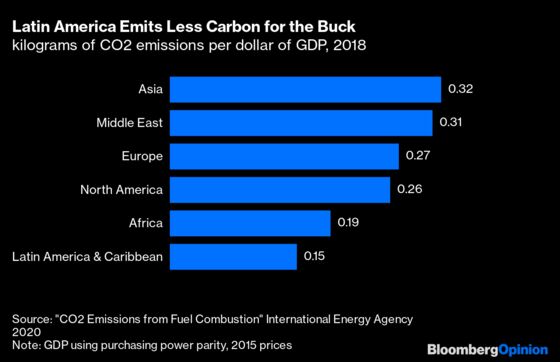

Latin American nations could capitalize on this fast-paced transition. The region starts with one of the cleanest energy matrices around, almost half of its electricity coming from green sources. It has huge solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal potential, from the Atacama Desert of Chile to the windswept sertao of northeast Brazil and the gales off Colombia’s northern shores, from the rain-drenched forests of Costa Rica to the volcanic ranges running through Mexico and Central America. It is also home to shale gas reserves that could bridge the transition from oil and coal to renewables. The economic promise reverberates beyond energy: Latin America’s low emissions and future clean energy potential should entice global manufacturers and services providers looking to meet their climate pledges.

Yet a virtuous circle of climate-friendly investment, jobs and sustainable economic growth looks less likely every day. As the world’s green shift accelerates, Latin America’s two biggest economies have gone in reverse. Mexico is doubling down on a fossil-fueled future. The Lopez Obrador administration has moved against renewable energy, sending wind and solar generators to the back of the electricity supplier line, raising both prices and pollution. Oil drilling and refining dominate the government’s capital outlays. And it has all but abandoned previous international climate pledges. These moves box out international investment in energy. And sooner rather than later, they will make it hard for Fortune 500 companies — among them, General Motors Co., Toyota Motor Corp. and Ford Motor Co. — to come or even stay in Mexico as its energy gets dirtier, costlier and less reliable.

Brazil, too, is out of sync with global trends. Carbon emissions have skyrocketed under President Jair Bolsonaro as his administration has enabled, if not encouraged, the Amazon’s deforestation by slashing watchdog budgets, undermining investigations and not even bothering to collect fines. In 2019, he withdrew Brazil’s offer to host the UN climate conference, undercutting the prominent global role Brazil once played in these negotiations.

Bolsonaro’s anti-environment stance has already taken a financial and economic toll. Several Nordic investment funds, comprising hundreds of billions of dollars, have divested. Textile manufacturers, including the maker of North Face, Timberland and Vans shoes, have stopped sourcing leather from the nation. And Brazil’s behavior has paralyzed the ratification of a EU-Mercosur free trade agreement that has been 20 years in the making.

Argentina’s financial woes and political shenanigans make it hard to attract money to exploit some of the world’s largest shale gas finds, and many ESG funds are already turning away from the idea of betting on such bridge fuels to a cleaner future. At the extreme, of course, is Venezuela, where investment is hard to entice, especially for the conventional fuels they are shilling.

There is still potential. Chile has set its sights on carbon neutrality by 2050; local and international money is pouring into new solar and wind generation projects and the electrification of public transportation. Colombia’s state-owned energy company, Ecopetrol, is planning for a less carbon-intensive future. Five Latin American nations joined U.S. President Joe Biden in April at his “Leaders Summit on Climate” (though some presented more convincing plans than others).

Latin American nations need trillions for infrastructure and other basic services to jump-start their economies and satisfy the aspirations of hundreds of millions of citizens. Even before Covid-19, public sectors couldn’t meet this demand. The trillions of dedicated dollars searching the world for green returns could fill much of this gap, with Latin America enabling these investors to do good and do well. And by bringing environmentally focused money and technologies to economies starved of both, this sustainable turn could help “crowd in” other foreign direct investment as it entices manufacturers and service industries trying to fulfill their own green bona fides. The money is attainable. But the policies need to change. And that will take pressure.

Local corporate heavyweights need to catch up with their own climate pledges and push their political leaders to follow suit. The Brazilian agricultural sector is starting after being shunned in some international markets, but needs to pick up the pace and pressure on its presidential advocate. In Mexico, international companies should push harder for change before deciding to scale back or just pull out.

The Inter-American Development Bank, U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, and other international financial institutions and programs can swell that chorus when they engage with the region’s governments and through their on the ground funding.

Civil society needs to raise its voice. In Mexico in particular, the environmental movement was undercut as a supposedly leftist president systematically gutted protection efforts and climate goals. It needs to reconstitute itself as opposition, and hold the enablers of Lopez Obrador’s misguided policies to account.

The good news is that Latin Americans care deeply about climate change (far more than Americans). Savvy politicians will find votes are to be gained by doing their part to slow the rise in global temperatures. If these forces bring political and policy changes, Latin America can have a better shot at a wealthier and more sustainable future.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shannon O'Neil is a senior fellow for Latin America Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.