Casinos’ Bugsy Siegel Problem Never Really Went Away

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Las Vegas Strip was built by a mobster. It took a billionaire to tame it.

That’s a paradox that’s been at the heart of the casino industry since its inception. Almost everywhere they exist, casinos depend on special licenses from the government that require them and their executives to follow high standards of probity. The nature of the gambling business, though, makes them highly vulnerable to criminal activity. Both licensees and licensors are all too willing to turn a blind eye to those risks in their pursuit of the profits and tax revenue that high rollers can bring in.

The latest casino business to get enmeshed in those contradictions is Crown Resorts Ltd., built and 36% owned by Australian billionaire James Packer. The company, worth A$12.6 billion ($9.8 billion) at its peak in 2014, is now valued at not much more than half that after a government inquiry found it was unfit to hold a gaming license because it had “enabled and facilitated” money laundering connected to its Melbourne and Perth casinos. Chief Executive Officer Ken Barton resigned Monday after the report questioned whether it should be allowed to hold a license for its Sydney gaming floors while he remained as a director.

The inquiry, by retired judge Patricia Bergin, lays bare the queasy gray area between rectitude and criminality that still pervades the industry, abetted by the willful ignorance of corporate and governmental figures.

The core risk for casinos is that they deal with vast sums of cash in ways that often make the sources and destinations of funds hazy. As with banks — a sector that’s also faced problems with money laundering in Australia in recent years — that makes them an ideal conduit for criminals who want to legitimize ill-gotten gains.

Preventing that sort of activity requires constant vigilance, paranoia about internal procedures, and the willingness to turn down profitable business if you can’t clear it through compliance. It’s abundantly evident from the litany of lax and shameful conduct detailed in Bergin’s report that Crown’s internal culture couldn’t have been more different.

There’s another sort of laundering at work here, though — not that of money, but of reputations.

Bugsy Siegel, an associate of Al Capone and Meyer Lansky, was the driving force behind the early development of Las Vegas’s casino industry. In those days, you’d shake up a casino’s management not by getting a judge to issue a damning report, but by ordering a gangland hit, like those that took out Siegel and his successor Gus Greenbaum.

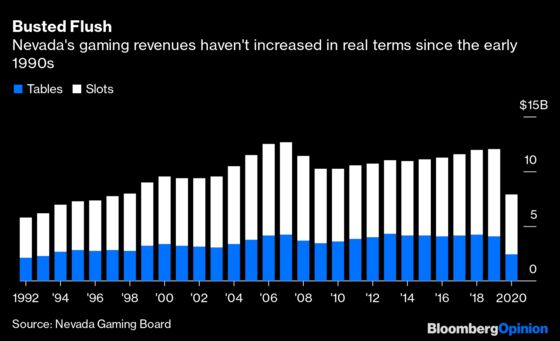

Vegas only shook off its seamy image after 1967, when oil, movie and aerospace tycoon Howard Hughes began to buy out many of the city’s biggest resorts, attracted by their abundant, utility-style cashflows. The city now makes more money from conferences, exhibitions and mass-market tourism than from gambling revenues, which haven’t increased in real terms since the 1990s.

Still, money laundering never really went away. U.S. casinos report about 50,000 instances of suspicious activity every year; listed companies include the risk of prosecution over such activities in their standard boilerplate of business risks disclosed to investors; and laundering investigations and legal settlements are more or less a regular cost of doing business.

In Australia, the Howard Hughes role is being filled by Crown’s James Packer. After inheriting the media empire of his high-roller father Kerry and selling up to switch into the gambling business, Packer had legitimate wealth and was presumptively deemed a fit and proper holder of a casino license. The problem, however, was with Packer’s connections in Macau — especially Stanley Ho, who built up that city’s gambling industry but was barred from doing business in Australia and the U.S. due to his alleged connections to organized crime.

Melco Resorts & Entertainment Ltd. — the vehicle through which Crown got a slice of Macau’s City of Dreams and Studio City casinos — is headed by Ho’s son Lawrence. It also appears to be owned in part by Great Respect, a trust of Stanley Ho in the British Virgin Islands. As late as 2019, Packer’s family company agreed to sell a 20% stake in Crown to Melco, in spite of assurances given in return for the Sydney casino license that it would be kept apart from associates of Stanley Ho.

There have been no allegations of mob links for other members of the Ho family, including Lawrence. Stanley Ho’s offspring still dominate Macau’s six casino licenses. His daughter Daisy Ho is chairman of SJM Holdings Ltd. and her sister Pansy Ho has the second-largest stake in MGM Resorts International’s local casino. A 2009 report by New Jersey’s Casino Control Commission ordered MGM to sever its ties with Pansy if it was to retain its stake in Atlantic City’s Borgata casino, citing her relationship with Stanley and inheritance of his wealth. MGM instead put the American resort into a trust and later successfully appealed for the decision to be overturned, arguing that Pansy Ho’s share in the Macau venture had shrunk and her relationship with her father had deteriorated.

The essence of money laundering is all about putting enough obscure steps between a criminal venture and a legitimate investment that the funds are cleansed of the taint of crime. It’s not so different with the reputational laundering that happens in the casino industry.

In Bergin’s report into Crown, the key recommendation is that the board and senior management must be replaced, an act that would leave its capital intact. The CEO is now gone; and Crown’s forward price-earnings ratio is not far below its highest levels on record . That suggests investors don’t expect a separate ongoing investigation by Australia’s money-laundering agency to levy too high a penalty, either.

If they’re right in that bet, Crown will end up cleansed of scandal and free to continue its lucrative business. Howard Hughes could scarcely conceive of a bolder second act.

Based on its blended forward 24-month price-earnings ratio. We've chosen a longer period to reduce the influence of Covid-19 on the valuation.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.