(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Class hasn’t had enough attention in the drive for workplace equality. Perhaps thanks to a British preoccupation with this topic, the U.K. arm of accounting giant KPMG is addressing the deficit. The firm has been analyzing its workforce by nosing around what employees’ parents used to do for a living. It’s a legitimate inquiry. The tricky issue is what to do with the answers.

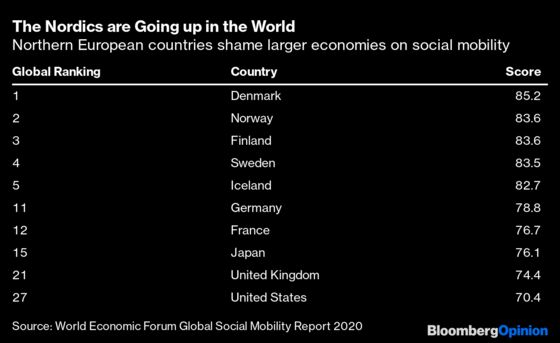

Socioeconomic status matters to diversity initiatives. The U.K. and U.S. perform poorly in global social mobility rankings. Data suggest it’s generally hard for many people in supposedly advanced economies to break out of the socioeconomic circumstances in which they grew up.

Businesses can’t pretend this is an issue for government alone. The education system is not the leveler it should be. Even possessing a degree doesn’t automatically unlock social mobility, and employers can perpetuate inequality in the way they hire and promote staff.

The onus on the oligopolistic financial sector is greater still. Its high pay contributes to broader income disparities. If the opportunity to make big bucks isn’t seen to be available to anyone with talent and drive, lawmakers will ask why some parts of financial services are allowed to run a semi-closed shop, and government will make life harder through regulation and taxation.

KPMG LLP has particular reason to address a socioeconomic skew in its workforce. The British firm audited collapsed construction company Carillion and stands accused of misleading the U.K. accounting watchdog. This raises doubts about the strength of its culture and capacity for internal challenge.

The organization has published workforce class composition since 2016, but it’s now setting a target that working-class representation across director and partner grades should be 29% by 2030. Currently, the measure stands at only 21% for the entire firm, rising to 23% among partners. That’s barely more than half the level in the wider U.K. population. KPMG concedes its middle ranks are currently even less representative of society than its top tier. Clearly, it needs to do something to prevent the leadership becoming less diverse as the next generation steps up.

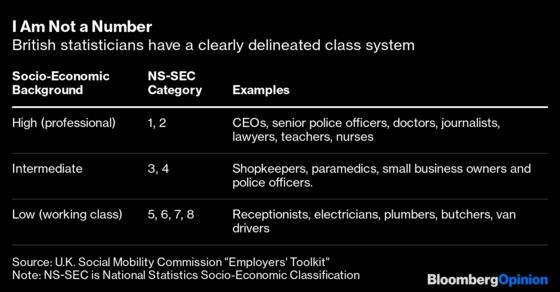

Setting targets, though, heightens the need for a robust methodology. KPMG’s approach is to ask staff to divulge the occupation of their highest-earning parent when they were 14. It then divides parents’ jobs into “professional,” “intermediate” and “working class” based on an established U.K. schema. This is far from a perfect measure of socioeconomic background, but it’s still a useful indicator. The question attracts high response rates and has fewer drawbacks than using types of schooling.

The auditor is also revealing class pay gaps (disclosure on pay disparities is mandatory in the U.K. only for gender). The median average remuneration of KPMG staff from working-class backgrounds is lower than those from professional backgrounds, the firm says. However, pay is slightly higher on a mean basis: Perhaps a handful of the partners who identify as working class are doing especially well.

Such disclosure is catching on: Rival PwC U.K. set out its socioeconomic pay gaps last week too.

But how to use the data? Sensibly, KPMG says the individual stats won’t be visible to hiring managers. This makes it more likely that respondents will answer honestly. It also removes the temptation to hire just to hit the target.

Things are also legally safer that way. Socioeconomic background is not covered by U.K. equality law. But a firm that uses it in hiring faces a legal risk, in theory, if failed candidates demonstrate they were subject to indirect discrimination. (The argument would be that class was closely correlated with a “protected characteristic” such as ethnicity.) Employers also face the iron law of the market: A perception of unfair recruitment practices could deter applicants.

The best application of such data is for personnel departments to ensure candidates are drawn from as deep a pool as possible, and to identify obstacles to promotion — as KPMG has committed to do. Headhunters scouting for middle-ranking roles will now be under more pressure to put forward broader slates. There should also be greater consideration of whether the stated qualifications for a job might in fact be excessive and needlessly narrow.

Of course, even without data, policies to promote social mobility make sense. Businesses should be offering work experience to schools in poorer areas, providing training and making managers accountable for casting wider hiring nets. But if you need to show the world these are working, only the data can prove it. Hopefully KPMG will do just that.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Hughes is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals. He previously worked for Reuters Breakingviews, as well as the Financial Times and the Independent newspaper.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.