Citi’s Problems and Solutions Look Suspiciously European

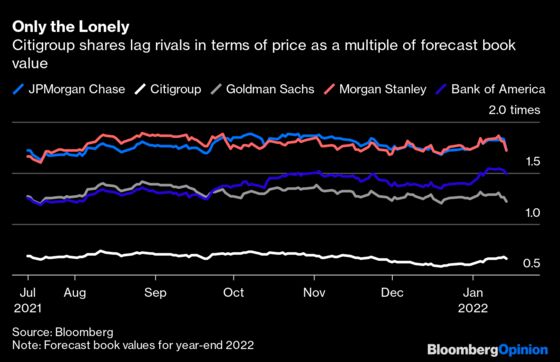

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Citigroup Inc. has long been valued like a European bank. Its British-born Chief Executive Officer Jane Fraser has reached for a European-style solution, but so far investors aren’t impressed.

The bank is on a mission to reshape its sprawling global businesses and make them simpler and easier to understand. It wants to invest in the parts of the bank that Fraser thinks can deliver the best returns and either sell or wind down those that can’t.

In reporting its full-year results on Friday, Citi also said it would change how it groups the results of the businesses it is focusing on to let its better-performing units show off their returns and separate the other stuff. That’s a very European move.

The overhaul accelerated this week after Citi put its Mexican consumer business up for sale and announced a deal to offload four Southeast Asian businesses for $3.6 billion. These moves followed the sale of businesses in Australia and the Philippines and a decision to wind down and close its Korean consumer arm.

But Citi’s share price fell more than 2% Friday, suggesting investors aren’t seeing a brighter future yet, although the added news that costs appear to be rising across the industry didn’t help.

Fraser wants to build Citi’s global private bank and wealth businesses outside the U.S. and at home, and these will sit alongside its U.S. consumer bank in the new reporting structure. The corporate and investment banking business remains much the same, but its numbers will be reported differently, split into banking, markets and services.

The idea with this sort of reporting rejiggering is to give investors a clearer idea of how good a bank they would own if it weren’t for weaker businesses dragging the good stuff down. They should then value the shares more highly even before the bottom line actually improves. Does it work? Ask investors in European banks and the answer will mostly be “no” — or at least not as quickly as executives would like.

Citi should free up a good chunk of capital once it gets out of the businesses it doesn’t want. About $12 billion of equity capital is tied up in the Asian, European and Mexican operations it is shedding and $2 billion more behind some legacy assets still left over from the 2008 financial crisis.

That would be good because Citi has less wiggle room on its capital than other big rivals. It did manage to buy back $7.6 billion worth of stock last year but has stopped repurchases while it adjusts to a new capital requirement for the industry. JPMorgan has bought back more than double that.

Underlying that is the problem of how to boost its returns. Analysts forecast that it will generate a return on equity of only 8% a year over the next three years.

Citi still has high costs related to meeting regulatory demands on risk, compliance and reporting; at the same time, costs are rising across the industry — led by higher pay for investment bankers. Meanwhile, revenue from investment banking and trading is likely to decline this year compared with the past couple of knockout years of activity boosted by government and central bank stimulus programs.

Citi wants to optimize returns in its markets business and win more clients among the rich entrepreneurs in Asia who might use its investment bank. Everyone thinks there are great profits to be had from both these efforts — but that’s why this narrative is so familiar and why so many banks are fighting to do exactly the same. In Asia especially, Citi could end up spending money that doesn’t generate the returns it desires.

Citigroup is the only large U.S. bank whose stock trades at a discount to its forecast book value for 2022: It is at 0.66 times, barely more than half the multiple of the next worst bank, which is Goldman Sachs at 1.22 times, according to Bloomberg data.

Investors are right to see a long, slow-going road ahead.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.