(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Dire as the coronavirus pandemic has become, it’s worth remembering that there are other severe public health threats that can’t be ignored. That’s a reason to applaud the Food and Drug Administration for issuing, even in this period, a tough new tobacco regulation that should save lives: It has required graphic warnings on cigarette packages.

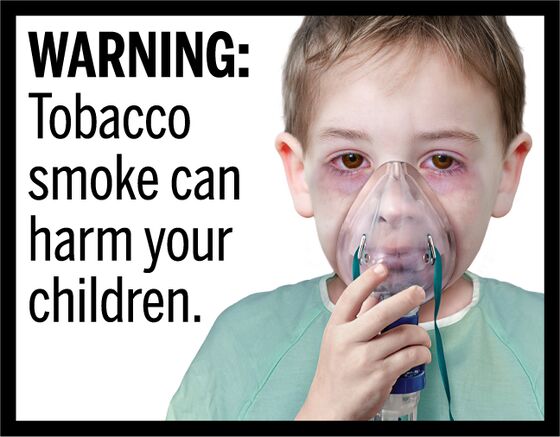

Whenever customers buy a pack of cigarettes, or stop to contemplate buying one, they will see one of 11 gruesome images, accompanied by a grim verbal message.

The image might be a woman with a large neck tumor, alongside these words: “Smoking causes head and neck cancer.” Or it might be a diseased lung, with these words: “Tobacco smoke causes fatal lung disease in nonsmokers.” Or it might be an obviously diseased body of a patient, with these words: “Smoking can cause heart disease and strokes by clogging arteries.”

The images cannot be small: “The new required warnings must appear prominently on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements, occupying the top 50 percent of the front and rear panels of cigarette packages and at least 20 percent of the area at the top of advertisements,” the FDA states.

About 480,000 Americans die each year from smoking-related causes. If that number can be cut even by 10 percent, it would be a spectacular achievement.

The new regulation ends a long saga. The current text-only warnings, in place since 1984, are bland. There is not much reason to think that they are doing any good. They were issued long before the explosion of modern behavioral research on how to trigger people’s attention about health risks by using arresting images.

In 2009, Congress enacted the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which mandated graphic warnings. The FDA issued the required regulation in 2011. But it was subject to a fierce challenge in federal court, with appellate judges ruling that the FDA had not established that its chosen warnings would actually save lives.

For the FDA, it was back to the drawing board – and slowly. It was not until 2018 that a federal court ruled that under the law, the agency couldn’t continue to sit on its hands. It had to take another crack at the problem, and do so promptly.

Last August, the FDA made its new proposal. The draft warnings were not quite as gruesome as those proposed in 2011, but they were in the same ballpark.

An important innovation, almost certainly adopted to reduce the risk of judicial invalidation, was that the agency did not claim to be able to quantify the number of deaths that its regulation would prevent. Instead, it chose to make the more modest claim that the warnings would promote “a greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.” There is every reason to think that the improved understanding will save lives.

Many observers applauded the FDA’s 2019 proposal. But in view of less-than-enthusiastic approach to new regulations by the administration of President Donald Trump, and the wide range of issues to which the FDA must attend, they were unsure whether the proposal would be finalized in a timely manner. It turned out that the agency acted expeditiously even in the midst of the coronavirus crisis.

As important as the new regulation is, it signals a broader point, especially when taken in the context of the coronavirus pandemic.

For applause-seeking politicians, it has been far too easy to call, in the abstract, for “deconstructing the regulatory state.” For mostly clueless observers in think-tanks, academia and elsewhere, it’s child’s play to cast contempt on the nation’s underpaid, expert bureaucrats and administrators, focused on public health and safety, as out-of-touch, or as obstacles to what really matters: free markets and business autonomy.

Deregulation can be a great idea, including in the area of medicine approvals, where the FDA should be removing “sludge” – and moving more quickly than it often has to allow promising treatments to reach the market.

But when tens of thousands of people are getting sick or hurt, and when their struggles and desperation are actually made visible, it looks less and less helpful – cruel, even – to celebrate a demoralized and hamstrung regulatory state, blocked from taking sensible steps to protect citizens.

Just for 2020, let’s stop calling it “the regulatory state.” Let’s call it “the protective state.” And let’s give it some running room.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Cass R. Sunstein is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is the author of “The Cost-Benefit Revolution” and a co-author of “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.