(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If the Trump presidency and Brexit convinced the European Union to start acting more like a sovereign power and less like a supermarket, Covid-19 has shown there’s a depressingly long journey ahead.

First there was fighting over protective medical equipment. Then the bungled start to its vaccine rollout. Now the scale of the bloc’s dependence on the U.S. and Asia in technology is being driven home hard.

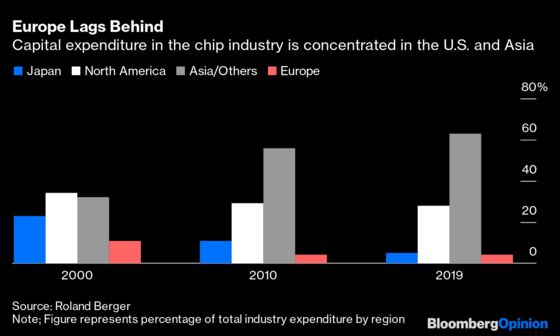

The semiconductor scarcity hitting global markets is a cruel reminder of how factories and know-how have left the continent. Meanwhile, the swelling market value of Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc., Netflix Inc. and Google-parent Alphabet Inc. shows where investors are placing future bets. U.S. tech’s total market capitalization recently surpassed the combined value of European stocks for the first time.

The EU dominates tech regulation, but that shows it’s better at defending its 400 million consumers than developing the new killer app. As France’s Emmanuel Macron said in December, the U.S. has the FAANGs and China boasts the BATX while the EU has its GDPR data-protection law.

To remedy the situation, officials in Brussels, Paris and Berlin have turned to industrial policy. Inspired by Airbus SE’s success in rivaling Boeing Co., state cash is being plowed into a sectors from electric batteries to cloud computing with the goal of creating pan-European champions. The latest endeavor is in chips, with the EU aiming to produce at least 20% of the world’s semiconductors by 2030 — double its current level — by using money from the bloc’s Covid recovery fund to build state-of-the-art factories.

However, the EU is lagging so far behind that the bloc is seriously in danger of missing yet another tech revolution.

Europe needs more than factories — it needs tech firms on home soil that would serve as customers, as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Alex Webb has argued. Otherwise, the result of this latest Airbus-style alliance with firms such as NXP Semiconductors NV and Infineon Technologies AG will be to better serve high-tech hubs abroad in the U.S. and Asia.

Cash is important, but so are the conditions that foster the innovative “ecosystems” the EU sorely lacks. According to entrepreneur Gilles Babinet, who advises the French government, the four key criteria are: Venture capital to fund ideas, universities to produce them, geographic clusters that attract deep-pocketed companies, and supportive politicians.

The EU is trailing in most of these areas: Its universities struggle to retain top talent, its venture capital pool is relatively small, and even with a new crop of billion-dollar startups there’s nothing to rival the likes of California or Shenzhen. Top-down policies are there, but not the seeds on the ground.

These are huge gaps to close for the new crop of Airbuses. The European electric-battery alliance comes after years of Asian dominance, and a new Airbus of cloud computing is disconnected from the reality of wealthy U.S. rivals like Microsoft Corp. and Amazon.

In an attempt to walk a middle path between the U.S.’s deep VC networks and China’s shamelessly statist approach, the bloc is failing at both. In 2000, EU leaders promised that by 2010 the bloc would be the most dynamic knowledge economy in the world. That didn’t happen, and China’s rate of innovation has increased five times as fast as the EU’s since 2012.

Europeans should go back to the drawing board and look not at Airbus, but ARM Ltd.

Crafted in Cambridge in the U.K., developed over decades and spun off with the help of Apple, ARM is a semiconductor designer whose technology is found in smartphones the world over. That made it an attractive takeover target, first by Japan’s SoftBank Group Corp. and now U.S. chipmaker Nvidia Corp. The pending deal is a “Sputnik moment”: ARM’s European customers fear that terms of access will be worse if a U.S. rival takes control of the company. Antitrust regulators are investigating.

This shows the double weakness of Europe: A lack of innovation centers that produce companies like ARM, and also of incentives that would help them scale up and compete on their own. Instead, too many promising tech firms are taken over by foreign companies. The sale of Germany’s robotics firm Kuka to Chinese investors is a good example. Strasbourg-based researcher Eric Rugraff says historically the EU’s approach to foreign takeovers has been an “open door policy.” New screening policies will help block sales of strategic tech, but it’s late in the game.

The original Airbus worked in its own way because all the pieces somehow fit together despite political meddling. Without more focus on encouraging innovation rather than ordering it up, another Airbus will be one too many.

Baidu Inc., Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Tencent Holdings Ltd. and Xiaomi Corp.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the European Union and France. He worked previously at Reuters and Forbes.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.