(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The welter of economic data released by China on Monday should put paid to any lingering notions that the government’s plans for a nationwide property tax are going anywhere quickly.

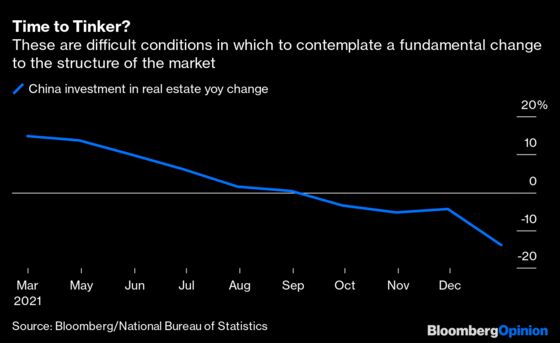

Conditions in the real estate market look increasingly challenging. Home sales slumped almost 20% from a year earlier in December, declining for a sixth month. Property investment fell 14%, and financing received by developers dropped by the most in more than seven years, Bloomberg News reported. Figures released last weekend showed new-home prices in 70 cities slipped for a fourth consecutive month.

Overseas investors are already acutely aware of the widening distress. Credit concerns have spread to a lengthening list of developers since China Evergrande Group was declared in default last month. Offshore bonds issued by Chinese developers have shed $82 billion in market value and more losses and defaults are likely unless the government eases property policy aggressively, according to Bloomberg Intelligence credit analyst Andrew Chan.

The signs of a shift are already here, though they’re incremental for now. The People’s Bank of China cut its key interest rate for the first time in almost two years before Monday’s first-quarter gross domestic product report. Regulators are encouraging financially stronger developers to take over weaker players, and prodding banks to finance such acquisitions. They have also urged banks to boost real estate lending and eased mortgage rules, while city governments are bringing in their own measures to support demand. If not looking to engineer a revival, authorities are at least intent on halting any downward spiral.

There’s never a good time to start radical reshaping of an industry that’s indispensable to a country’s economic model — even when such change would be unquestionably advantageous for fiscal health and social stability in the long run. That’s why the renewed push for a property tax, signaled in May last year as part of President Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” campaign, always warranted a dose of skepticism. The tax has been debated for more than a decade, but it has gone no further than limited trials in Shanghai and Chongqing that make insignificant revenue contributions.

Last May, the chief financial impediment was that the tax would mean tinkering with the foundations of an epic bubble that has helped to turbocharge China’s growth and wealth creation for decades. Now that the long real-estate boom is, arguably, starting to implode, authorities have little choice but to shift their priority to managing the process and restoring stability.

That’s without even factoring in the predictable political opposition to the tax, inevitable in a country where so many people, including Communist Party members, have so much of their wealth tied up in property ownership. By October, when the National People’s Congress passed plans for an expanded pilot program, it had already been scaled back to 10 cities, from a reported 30.

Even that more modest target may now be in doubt. “Now may not be an appropriate time to launch the trials as the economy and the real-estate market are both under pressure,” Liu Jianwen, a Peking University professor who is legal adviser to the Finance Ministry and legislative adviser to the NPC standing committee, told Bloomberg News this month.

Don’t expect the program to be abandoned completely. Too much political capital is tied up in it. Xi will seek a precedent-breaking third term as China’s leader at a party congress later this year, and his common prosperity drive is a signature initiative. It’s more likely to end up as a kind of Potemkin tax, existing in name and standing as evidence of the government’s determination to address inequality, while shorn of any scale or revenue-raising capabilities that would meaningfully affect the market.

A popular saying among Brazilians battered by perennial economic disappointment is that theirs is the country of the future — and always will be. In the same spirit, China’s property tax is earning a reputation as the great fiscal reform that never arrives.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matthew Brooker is a columnist and editor with Bloomberg Opinion. He previously was a columnist, editor and bureau chief for Bloomberg News. Before joining Bloomberg, he worked for the South China Morning Post. He is a CFA charterholder.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.