Chinese Investors Are Playing a Game of Hot Potato

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The star that burns the brightest may also burn out fastest. Investors tempted by the blazing debut of China’s new tech board should bear that in mind.

The first 25 companies to start trading on Shanghai’s Star market posted an average gain of 140% on Monday. The value of shares that changed hands surpassed 48 billion yuan ($7 billion) – about 13% of the total trading volume on Chinese exchanges, which contain more than 3,800 listed securities and have a combined market capitalization of more than $6.6 trillion.

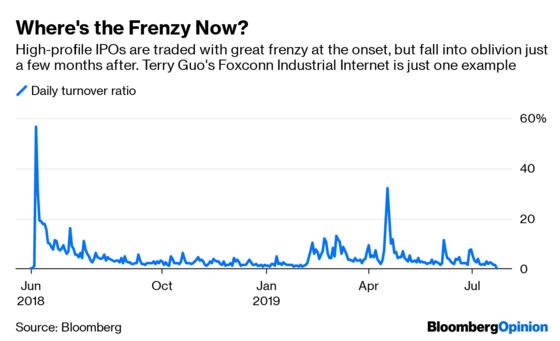

To some extent, this shouldn’t be a surprise. Playing IPO stocks is a national pastime in China. After Terry Guo’s Foxconn Industrial Internet Co. made its debut in Shanghai in June 2018, as much as 55% of the semiconductor manufacturer’s shares traded daily. Seen in that light, Monday’s 80% turnover ratio for Star stocks isn’t that remarkable – companies on the Nasdaq-style board are much smaller than the $35 billion Foxconn unit.

For the Star board to be a long-term success, it needs to maintain that level of liquidity. China’s track record on this front isn’t good, though. After a frenzied start, trading in newly listed shares tends to collapse.

There are many examples. Daily turnover for Foxconn has evaporated to about 2%. Shenzhen Mindray Bio Medical Electronics Co., which withdrew its U.S. listing to return home to China, has seen trading dwindle to minuscule levels since a high-profile IPO in October.

It’s worth asking why Chinese investors love to bet on newly listed stocks, a practice known as “da xin.” IPOs have been subject to an unofficial valuation ceiling of 23 times earnings, regardless of how fast companies are growing. That’s meant systematic undervaluation and a one-way bet when they come to market. But the price-earnings cap has been removed for the Star market, which follows the U.S.’s registration-based model. So why are investors still piling in?

The sad reality is that China’s stock market isn’t a good place for long-term investing. Unlike the U.S., where investors can reliably expect a 5% cash yield from dividends and share repurchases, buy and hold is a losing strategy. Over the past 12 years, investors get back only 38 cents for every dollar they give to companies, data provided by Citic Securities Co. show. China Inc. isn’t into cash rewards.

In other words, companies treat public investors as free ATM machines. So for investors to make money, they have to punt on share-price gains. “Da xin” is essentially a process of passing hot potatoes to the next investor.

The Star board, the brainchild of President Xi Jinping, is considered a key policy in China’s new supply-side reform. In Beijing’s view, insufficient market-based financing has contributed to China’s ballooning debt problem. Two-thirds of corporate financing comes in the form of bank loans. The Star board is intended to spur direct financing, where companies raise money from investors through corporate bond and stock offerings.

It’s not the first such attempt. The ChiNext board in Shenzhen started almost a decade ago to provide an alternative fundraising venue for smaller firms. It’s since fallen out of favor. China’s stock market will need more fundamental change if Shanghai’s Star is to avoid the same fate.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.