China’s Macau Crackdown Attacks the Symptoms, Not the Cause

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In many ways, it’s surprising the crackdown didn’t come any earlier.

After attacks on Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and Didi Global Inc., effeminate actors and online gaming in pursuit of the austere spirit of President Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” goals, it was only a matter of time before the decadent opulence of China’s sin city came under scrutiny.

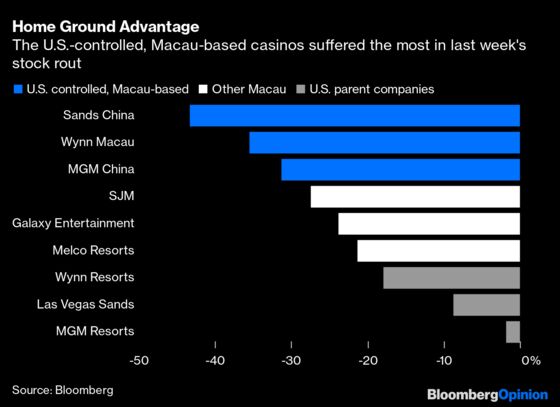

Macau will increase supervision of casinos and the junket operators that help finance high rollers, the nominally self-governing territory announced last week. That could have a devastating effect on the world’s largest gambling destination, where players lost some 292 billion patacas ($36.5 billion) in 2019 and three of the six casinos are controlled in part by U.S. gaming giants Las Vegas Sands Corp., Wynn Resorts Ltd., and MGM Resorts International. Shares collapsed last week, with Sands China Ltd. losing nearly half its value.

The announcement feels very much like a rerun of events in 2014, when a crackdown on official corruption in the early years of Xi’s reign forced casino operators to scale back plans to lure VIP gamers betting tens of thousands of dollars per hand and move to mass-market gambling instead. Casinos have spent most of the intervening period climbing out of the crater brought on by that action, with net income of the six licensees rising to about three-quarters of 2014’s total in 2019. Then Covid hit. With this latest setback, you might think the casino operators are all out of chips.

Even so, anyone who believes the changes will bring more order to China would be mistaken. There’s little evidence that nearly a decade of Xi’s anti-corruption drives have had much effect on the billions of illicit yuan oiling the wheels of society, most of it without going anywhere near the gambling industry. Registered corruption cases involving party officials have increased more than four-fold over the decade through 2010.

That figure may be tainted, both because it could reflect more robust enforcement and because such cases are often more about politics than graft in China. Even so, other measures point in the same direction. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators suggest corruption levels were around the same in 2019 as they were when Xi came to power in 2013, putting the country on roughly the level of Brazil or Kazakhstan — neither a byword for honest governance — and well behind the likes of India, not to mention every developed economy.

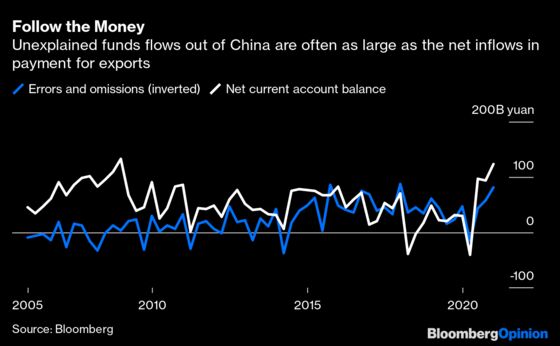

More telling is a look at the country’s balance of payments. “Errors and omissions” — the number required to reconcile the movements of goods, services and income in the current account with the financial transactions in the capital and financial accounts — are often seen as a proxy for dark-money capital flight out of China. They’re the shadow left when officials move their wealth out of Beijing’s reach. With Macau seen as one of the chief conduits of such illicit transfers, it’s precisely that sort of activity that the crackdown might aim to prevent.

In truth, though, errors and omissions have boomed under Xi, from 87 billion yuan ($13.5 billion) in 2013 to as much as 219 billion yuan in 2016 and 168 billion yuan even last year, when international travel and the opportunities it brings for cross-border flows were severely restricted. The value of such untraceable sums is frequently greater than the net balance of all goods and services traded by China. If the country is living in a new era of austerity and probity, it’s hard to know what’s fueling these flows.

That’s reason to suspect that Macau’s latest crackdown will have a worse bark than its bite. Macau’s pact with Beijing is like a plusher version of the social contract the Chinese government has with its own people: Accept the ultimate authority of the Communist Party, and you can earn the sort of income that’s turned the city into a jurisdiction richer than Norway or the U.S.

Of the key measures being proposed — tighter supervision of day-to-day operations, more control over dividend payouts, and increased local shareholdings — only the first does much to affect cross-border movements of money, which had more or less regained their 2013 level before the pandemic. The latter, if anything, suggests an excellent opportunity for connected locals to buy into lucrative businesses at a fire-sale price. And all just in time for the renewal of major casino licenses due next year, likewise a perfect moment for Macau’s government to take its own larger share of winnings.

That’s the impression you’d get looking at the performance of share prices, too. Sands China has arguably done more than any other operator to embrace the post-2014 move to mass market tourism, with vast indoor shopping malls at its Venetian and Parisian casinos. Despite that, its shares suffered the most, along with the other U.S.-controlled gambling companies. Local rivals fared far better.

Separating local sheep from foreign goats isn’t the hallmark of a government determined to stamp out graft. Quite the opposite.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.