This Week May Turn the Tide on Two Centuries of Emissions

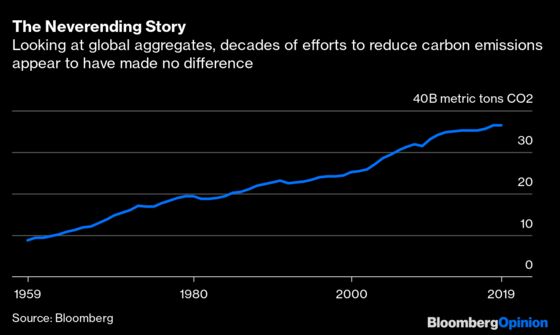

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Looking at the way the world’s carbon emissions have risen in recent decades, it’s tempting to believe that increasing pollution is an ineluctable law of nature.

That’s by no means a heretical view. Vaclav Smil, the Czech-Canadian energy analyst revered by Bill Gates, has often pointed to the growth in pollution since the 1980s as evidence that a transition to cleaner forms of energy will inevitably come too slowly to save the world from disaster.

“During those decades of rising concerns about global warming the world has been running into fossil carbon, not moving away from it,” he wrote in one 2019 study. Climate scientist Ken Caldeira made a $2,000, 10-year bet with energy analyst Ted Nordhaus in January that 2019 wouldn’t prove the peak of global carbon emissions.

On global aggregate numbers, it’s hard to gainsay that conclusion. Over the decade through 2018, emissions increased by 12%, or 4.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide. A decade or so of further pollution at that level will eliminate all possibility of avoiding catastrophic warming.

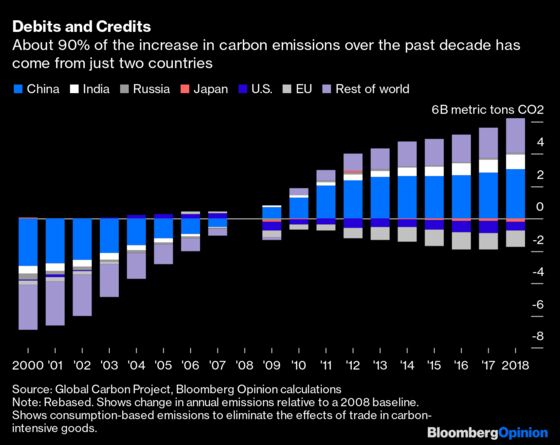

Break out the numbers by country, however, and a very different picture emerges. Some 89% of the additional greenhouse gases came from just two countries: China, which alone accounted for 69% of the increase, and India. Emissions from the EU, Japan and U.S. fell, and by 2018 were lower than they were in the 1990s.

That’s why the climate and energy plans that will be presented in China’s 14th Five Year Plan this week represent the most important policies being made anywhere in determining the fate of the planet. If they live up to the promise of President Xi Jinping’s pledge to reduce the country’s emissions to net zero by 2060, we may have to start lifting our expectations of what’s possible in terms of decarbonization.

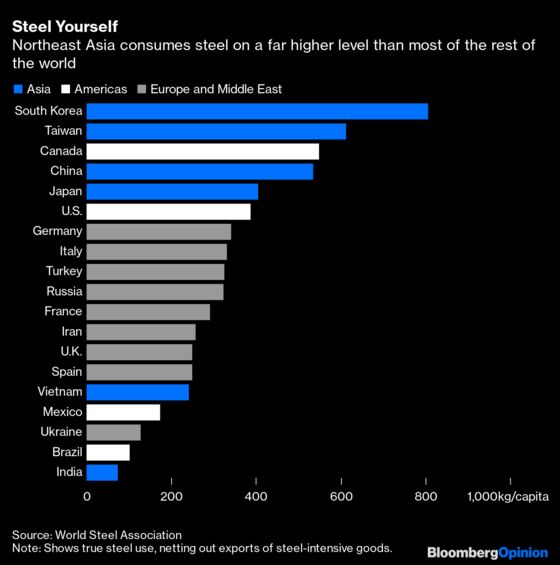

The unprecedented scale and carbon-intensity of China’s boom has served to obscure much of the progress made elsewhere in the world over the past decade. To name just two products, the country now makes more than half of the world’s steel and (in a parallel first pointed out by Smil) consumes about as much cement every two years as the U.S. did during the 20th century.

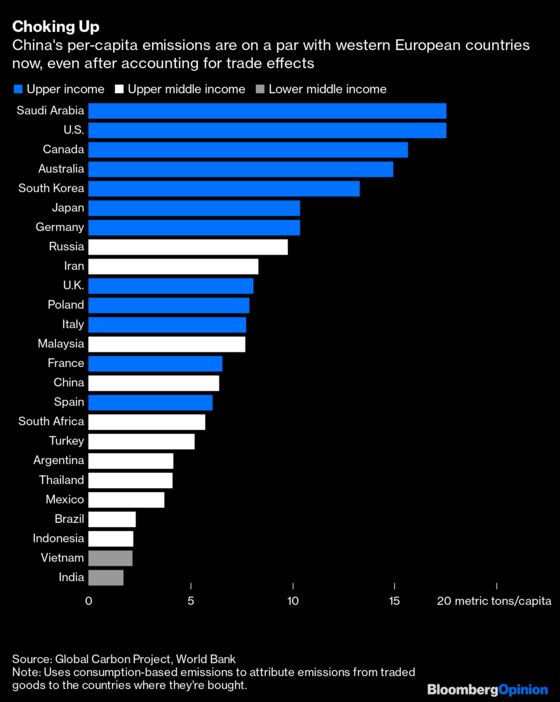

The days when China could argue that those numbers were huge only because its population was large, or that they were necessary to catch up with richer countries, are now in the past. Even if you adjust for the effects of trade by using consumption-based emissions — so that, for example, a laptop made in Chongqing and sold in Toronto counts toward Canada’s carbon budget, not China’s — its per-capita emissions these days are on a par with most western European countries.

In terms of infrastructure, too, the construction boom of the past decade has left China with a public capital stock that’s larger on a per-capita basis than Germany, South Korea or the U.K. The population of China still trails rich countries by income and welfare protections, not to mention human rights. When it comes to the high-emitting business of pouring concrete and rebar, however, it’s as rich as any country on earth.

That’s not really meant as a criticism of the energy-intensive development path taken by both China and India — just an indication of how transformative a turn toward greener growth would be, not only in emerging Asia but for the world. When these nations embarked on their current expansions, the idea of becoming wealthy without catastrophic carbon pollution seemed unfeasible. In the words of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, poverty was the greatest polluter — implying that a country couldn’t be free of both scourges. Now renewables are the cheapest source of power almost everywhere, Gandhi’s successor Narendra Modi is promising to build 450 gigawatts of renewable power by 2030, and emissions-reducing growth is the explicit target of the Chinese government.

It’s still unclear whether the final document presented to the National People’s Congress will live up to the hope of Xi’s net-zero promise. As we’ve argued, a target announced in December of building 1,200 gigawatts of wind and solar by 2030 would be inadequate to stop the rise in China’s emissions, and is substantially less than what the renewables industry claims to be capable of building.

At the same time, there have been signs that ambition is being quietly stepped up. A high-level audit into the country’s National Energy Administration last month criticized its failure to rein in coal generation in unusually forthright terms. A circular issued by the governing State Council last week promised a “noticeable improvement” in environmental development by 2025, without offering many specifics of what that would constitute. In India, too, a study of the power system by think-tank the Energy and Resources Institute concluded there’s no economic case for building more coal-fired generation.

We’ve not really prepared ourselves for what the world will look like when China and India switch from being headwinds slowing down global decarbonization, to tailwinds accelerating our path toward zero. Even the emissions cuts chalked up in rich countries in recent years have been far too slow. But as the costs of renewable power fall with each passing year, those reductions will grow deeper, and spread further around the world. There will be a titanic battle over the coming decade to start reversing two centuries of carbon addiction. This week could be the moment when we finally start to turn the tide.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.