China’s Energy Crisis May Be the Birth Pangs of a Better Grid

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Never let a good energy crisis go to waste.

That’s been the maxim of lobbies on each side of the climate debate as power prices have spiked and blackouts spread from Australia, to Texas, and the U.K. in recent years. Those who rightly wish to speed the transition away from fossil fuels see the failure of largely thermal-powered electricity networks as a spur to remake an energy system that’s already failing. Those who want to impede that progress see it as an opportunity to smother renewable power before it grows any bigger.

That battle is now playing out in China, where a swath of provinces are contending with power rationing after the price of coal spiked. Thermal generators have switched off rather than lose money selling power at regulated tariffs, leading to production halts at aluminum smelters, textile plants, and soybean processors. In Liaoning province, a traditional industrial powerhouse east of Beijing, even traffic lights and homes have lost power for brief periods.

It’s likely that the coal faction will win the first round of this fight. At bottom, the current crisis is a fuel shortage. China still has ample generation on tap, at least on paper. Its mostly coal-fired thermal power plants have been running at barely more than half capacity all year, a mild improvement on recent history but still far short of levels they’d need to make a decent return. The problem is that with strong power demand, hydroelectric dams underperforming, and the first cold snap of winter coming early, there’s simply not enough black rocks around to power their turbines.

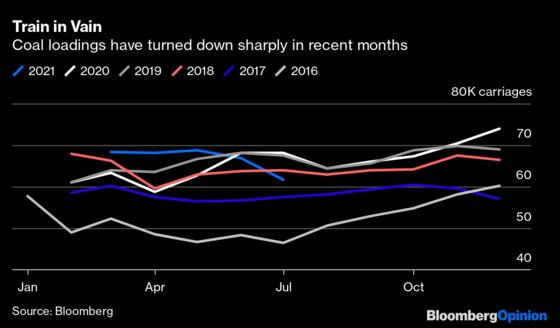

At China Shenhua Energy Co.’s Huanghua port, volumes in August were down 2 million metric tons from the same period a year earlier, a 10% decline. China Coal Energy Co.’s production was also 10% lower from a year earlier, representing a 1 million ton drop. Loadings of coal onto rail carriages, after starting the year strongly, plummeted as the summer wore on, and in July hit their seasonally lowest levels since 2017. All this at a time when electricity demand has been growing at its fastest pace in a decade.

Still, the fact that an energy crisis is happening in China at all is, in its way, a positive sign. In the past, the first instinct of government would be to bail out the state-owned generators who are losing money on 1,377 yuan ($213) a ton coal and keep prices to industrial users artificially low, according to David Fishman, a manager with Lantau Group, a Hong Kong-based energy consultancy. With the travails of China Evergrande Group indicating that Beijing is turning off the money tap, that tendency is receding.

Electricity price suppression is a reason that China is one of the world’s least energy-efficient major economies. Allowing costs to rise should help factories be more thrifty in their power usage. “End users have to get used to the idea they have to pay more for power,” says Fishman.

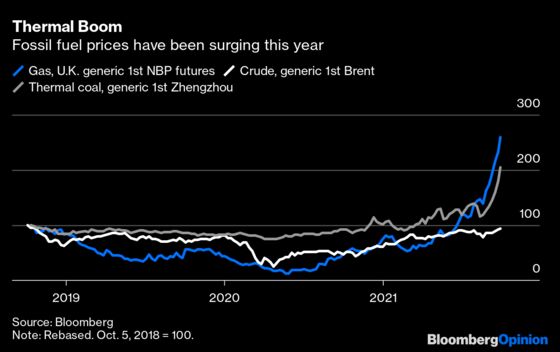

For now, the quickest way to prevent the current situation escalating any further as the temperatures plummet in northern China will be to do what the price signal of that $213 coal is indicating — dig up and burn more fossil fuels. The governor of Jilin province, one of those hit by the cuts, made exactly that appeal on Monday. That will have knock-on effects around a globe that’s fighting for every scrap of hydrocarbons right now, with Brent crude above $80 a barrel and U.K. natural gas above 2 pounds a therm.

Given how rapidly the world needs to be reducing carbon-intensive energy over the coming decade, that likely shift is grim news. Yet there’s a silver lining that will be easy to overlook in the coming months: What the world is short of is ultimately not coal and gas, but energy. In the short term, fossil fuels are likely to be the quickest ways to bridge the power gap — but in the long term, the market is going to seek the cheapest alternative. Almost everywhere in China and around the world, that is now renewable.

The most striking sign of where this is heading can be seen in the way that the economic planners at the National Development and Reform Commission are rethinking their rules on the power industry. For the past five years, this has been guided by the so-called “dual control” system — hard targets issued to provinces to limit energy consumption and increase energy efficiency. Despite good intentions, those controls have failed to incentivize sufficient renewable generation.

That may be changing. In revised guidance on the rules issued earlier this month, renewable power will be exempt from the consumption caps, while major energy-hungry projects must receive approval from Beijing before going ahead. That will make it far more attractive for provinces to build extra wind and solar parks, where they’ve hitherto been held back for fear of breaking their energy consumption limits. “China is transiting from an energy intensity target to a carbon intensity target,” says Yan Qin, an energy analyst with Refinitiv, a financial data business.

Energy modelers have long complained that the recent pace of renewable build-out, while astonishingly rapid, is woefully insufficient to turn the corner on emissions. China’s next five-year plan envisages building barely half of what’s needed to halt the rise in power sector emissions. The current surge in thermal power prices may be precisely the catalyst to unlock those necessary investments.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.