(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Foreign investors aren’t particularly fond of the Chinese government lately. They’ve lost billions of dollars since Beijing started its crackdown on the country’s tech and real estate stars. But let’s look at the bright side: China was cleaning up companies with flimsily structured asset — stocks and bonds that investors shouldn’t have had in their portfolios in the first place. Beijing may seem not to care how much money you’ve lost but, believe me, the Chinese authorities are doing you a favor.

There are two ways that most foreign investors get into mainland companies: Offshore dollar bonds or stocks listed in New York or Hong Kong. Beijing’s recent regulatory campaigns were mostly a big whack at these overseas securities for many reasons, but most importantly because the Chinese companies adept at raising billions of dollars offshore also tend to be financial houses of cards.

Often incorporated in Cayman Islands, hot tech names listed in New York and Hong Kong raise capital offshore but do not own their mainland operating units outright. The relationship with the onshore money maker is often contractual — and it can be broken. When things turn sour, foreigners get minimal protection — and little to no chance of getting any of their investment back.

How do you even value these kinds of companies when they get distressed? Investors are now learning to look only at their offshore assets — not just the shiny mainland Chinese ones on the covers of the sale brochures.

Take China Evergrande Group, Asia’s largest high-yield dollar bond issuer. Its bonds are trading for as little as 45 cents on the dollar and its ratings have been slashed. Investors are now trying to figure out its endgame: whether it will have to go through debt restructuring, bankruptcy, or liquidation.

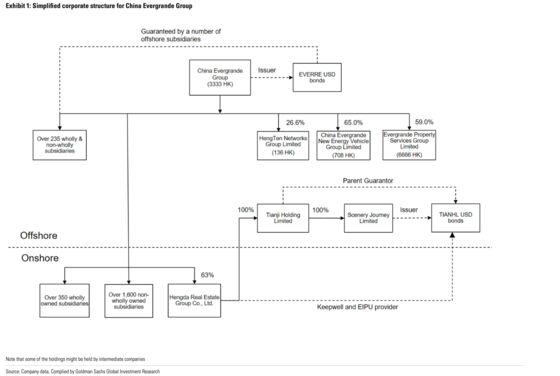

The real estate developer tapped into the offshore dollar bond market in two ways. Most of its bonds, or $17.3 billion outstanding as of 2020 year-end, were issued by the offshore parent, which is incorporated in Cayman Islands, with guarantees from a number of offshore subsidiaries. The rest, or $6.1 billion, were issued by an offshore special purpose vehicle, owned by its main onshore real estate unit, Hengda Real Estate. Rather than an outright guarantee, these bonds only have keepwell clauses — essentially gentlemen’s agreements. Hengda is the Chinese pinyin translation of Evergrande.

How much money can foreigners claw back? Forget about squeezing anything out of the conglomerate’s mainland holdings. Credit analysts are now looking only at Evergrande’s offshore assets — among them, the EV and property management units listed in Hong Kong as well as a stake in internet firm HengTen Networks Group Ltd, according to Goldman Sachs Group in an August 7 note. Bloomberg Intelligence’s Patrick Wong has raised the possibility that Evergrande’s residential projects in Hong Kong may be disposed of, too.

In other words, if you as a foreign investor bought into Evergrande, you didn’t really buy into China’s second largest real estate developer. Instead, your money is in an investment company with a few buildings dotted across Hong Kong. As for the bonds issued by the Hengda special-purpose vehicle, good luck arguing in mainland courts on the validity of those keepwells.

Even with all that, Evergrande’s investors are fairly lucky. Billionaire founder Hui Ka Yan has over the years developed substantial economic interests offshore and so his company’s bonds are worth something to overseas investors if things go wrong. In the worst case, foreigners can force Evergrande to liquidate its equity holdings, or its Hong Kong properties, even if at fire sale prices. In an exchange filing in Hong Kong, Evergrande said it was in talks to sell stakes in its EV and property management unit. No concrete plan or formal agreement has been entered into.

The hot new tech brands can’t provide investors anything comparable. They are asset-light overseas; and the money they raise in foreign markets is often funneled back to China for business development. Net cash position is the key metric to look at, but you also have to figure out how much of it is held abroad. For foreign investors, the recovery rate can be as little as zero for outfits like New Oriental Education & Technology Group Inc. or TAL Education Group — the for-profit education companies that Beijing has ordered to become nonprofits.

One example with a glimmer of hope is the disgraced coffee chain operator Luckin Coffee Inc., which entered bankruptcy in the U.S. Its onshore business operations seem to be doing just fine, hitting store-level profitability for the first time last August. So, if Luckin somehow re-lists in New York, its bond investors, as well as those who trade its shares on pink sheets, may be able to get some recompense, even reward.

China still has a formidable capital and legal firewall, so it’s very important to remember the difference between offshore and onshore. A company can have the most amazing money-generating machine in mainland China, but the offshore parent — the one that many investors bought into — is often just a shell. The parent will play nice only if it wants to raise more money down the road.

The mainland stock and bond markets are more difficult to access, but foreigners will have greater protection there. The Chinese government is quite serious about instilling market discipline and good corporate governance. It does want investments from overseas — as long as it’s not the hot money that swirls around chasing short-term gains. So, if you do manage to get yourself onshore and you lose money, go complain to the securities regulators. They know how to make companies behave.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.