Xi’s Coal Pledge Is Climate Followership, Not Leadership

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As a second act, it doesn’t quite match up to the promise of the original.

At last year’s United Nations General Assembly, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised to reduce his country’s emissions to net zero by 2060 and hit peak pollution by 2030. That was a genuinely striking commitment from a country that had long chafed at pollution controls. At this year’s meeting, he pledged to end the financing of coal-fired power stations overseas. That will have more of an immediate effect — but unlike last year’s announcement, it’s a fait accompli in all but name.

That's because the dwindling pool of countries still prepared to accept Chinese funds to build coal-fired power have been quietly quitting the field for some time, driven as much by the vanishing commercial appeal of solid fuel as by any climate commitments.

This doesn’t diminish the importance of the announcement. Just a few years ago, the idea of an end to new coal plant construction was seen as a provocative, even improbable idea. In 2015, the International Energy Agency expected demand of 5,814 million metric tons for 2020 — already a 500 million ton downgrade from its previous forecast. In practice, it was 5,168 million tons, and is only expected to revive to 5,308 million tons in the wake of the pandemic this year. That pace of decline needs to accelerate dramatically over the next five years, rather than slow to a halt as the IEA currently predicts — but the end of Chinese coal finance will play a major part in that process.

Commercial finance has long since backed away from building new coal-fired power. Rich countries are already turning their thermal boilers into scrap at a furious pace, with nearly a third of the U.S. coal fleet retired since 2011. The remaining growth markets are in emerging economies where private lenders are more reluctant to fund any projects, let alone polluting generators that make little commercial sense and may take decades to pay off their debts.

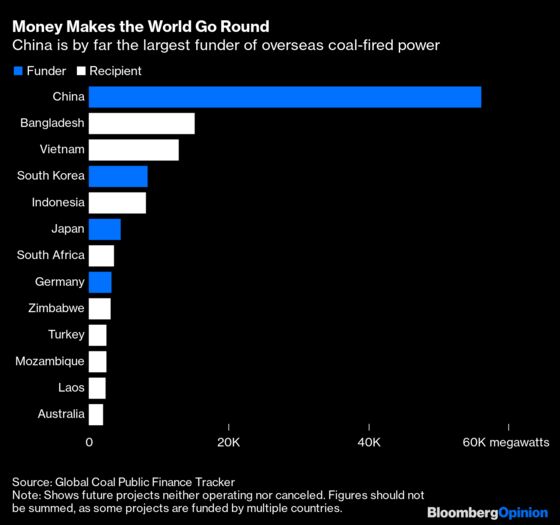

With the withdrawal over the past year of South Korean and Japanese state financing for such projects, China has been left as the only game in town. Leaving aside one 600-megawatt plant with South African backing in Botswana, all of the 63,115MW of plants under development identified by the Global Coal Public Finance Tracker database depend on those three countries. Only those generators already under construction are likely to ever be switched on, leaving about 40,000 megawatts facing cancellation. That’s equivalent to switching off Germany’s remaining coal fleet at a stroke.

In truth, the writing has been on the wall for some time for many of the largest recipients of Chinese coal finance. Bangladesh in June formally canceled 10 coal plants it had under development, totaling 8,451MW, while Pakistan — one of the largest recipients of China’s Belt and Road funding, much of it for developing coal-fired power — last December announced it wouldn’t build any more solid fuel generators. The Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia have made similar announcements over the past year, rounding out the list of Asian countries that were set to see the largest amount of overseas-financed coal development. It’s a lot easier to announce the end of funding for a technology when there are no customers for it in the first place.

The reasons for those cancellations have only a little to do with climate commitments. Emerging economies have long hewed to Indira Gandhi’s maxim that poverty and need are the greatest polluters: Rich countries, responsible for most of the fossil carbon already in the atmosphere, should be the ones to worry about the climate; the rest of the world just needs cheap electricity.

What’s changed is that coal is no longer a reliable path to that goal. Even if you set aside the near-term damage that fossil fuels do to public health and the long-term risks of a warming planet to countries that are already over-exposed to heat and extreme climatic events, coal simply doesn’t stack up economically. New renewables are competitive with even existing fossil-fired power in countries representing nearly half the world’s population, according to BloombergNEF; in countries accounting for 91% of electricity generation, wind or solar is already the cheapest option for new power plants. That's exacerbated by the fact that the key determinant of coal power costs is fuel, a volatile commodity that is currently changing hands for roughly three times the price those estimates are based on. If you want cheap power, these days you need renewables.

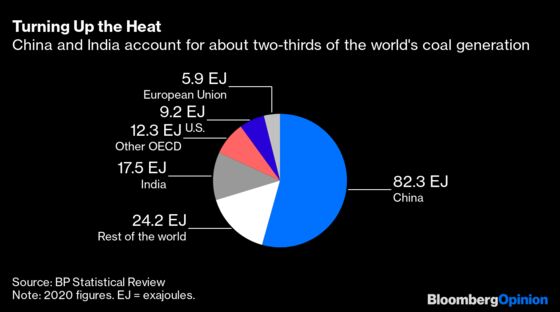

The elephant in the room is what’s happening on Xi’s home turf. China and India are the real markets to watch to gauge the future of solid fuel. Largely self-sufficient both in finance and in mineral reserves, their coal fleets account for about two-thirds of consumption worldwide and are deeply embedded in social and political structures that pass the environmental and fiscal costs on to consumers. Thermal power is clearly struggling in both markets, but neither has made the sort of near-term phaseout plans announced in richer economies. Elsewhere, too, the past year’s wave of coal cancellations has seen emerging economy governments largely maintain their commitments to gas-fired power, rather than switch wholesale to zero-carbon generation.

Still, with Xi’s announcement, a vision of development that began in the British industrial revolution — with coal as the indispensable fuel to kickstart industrialization and growth — looks ready to be buried. A cleaner future beckons.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.