(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In the past, China Evergrande Group has always been able to wiggle out of trouble. In turbulent times, billionaire founder Hui Ka Yan would turn to his tycoon friends to prop up his stocks and bonds. The persistent support they’ve provided — buying up Evergrande debt — is why the developer is also Asia’s largest dollar junk bond issuer.

Hui’s pals were at it again earlier this week. As the real estate developer’s bonds tumbled to record lows, CST Group Ltd. said in a filing that it had bought $11 million worth of Evergrande bonds on the open market. Billionaire Cheung Chung Kiu — one of Hui’s buddies in what’s called the Big Two poker club — has a stake in CST. Last September, during another credit crunch, the investment firm bought Evergrande bonds as well, helping to stabilize a market that had grown jittery over another bad turn in the property developer’s fortunes.

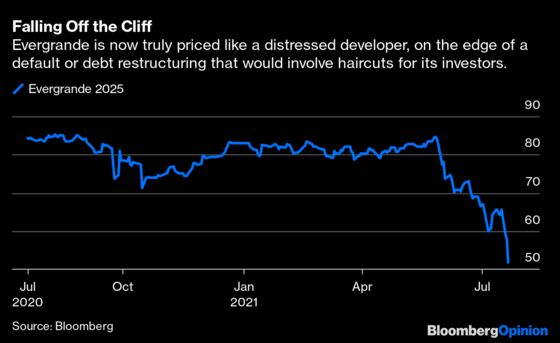

Friends may not be enough now. This credit crunch is a lot more severe. With Evergrande’s 2025 dollar bond trading at only 50 cents on the dollar on Wednesday, it’s clear investors are already pricing in a potential default. Furthermore, fresh revelations this week have called into question how much cash Evergrande really has on hand to cover bonds that are coming due. The endgame is near.

First, Evergrande is going to have a harder time converting apartment sales to cash. Like other property developers, it’s benefitted from a practice common in China called pre-sales: Consumers pay the full price of homes before they are built, handing over a lump sum and mortgage borrowing. In theory, there’s an escrow account to ring fence client money; but, in practice, developers have often tapped into these payments early, especially when they don’t have any other channels for funds.

On Monday, Shaoyang, a fourth-tier city in Hunan province, called out this practice. The city government said it had halted sales at two of Evergrande’s residential projects. Out of 290 million yuan (nearly $45 million) in Evergrande home sales made this year, only 106 million yuan appeared in the designated escrow account, the city complained. Shaoyang reversed its decision only after Evergrande wired 128 million yuan into the account and promised the rest when banks release their mortgage loans. In other words, Shaoyang said: Put the money where it belongs, or stop selling property.

Evergrande’s certainly not the first to have trouble with pre-sales. Last year, distressed luxury villa developer Tahoe Group faced pressure from hundreds of pre-sale customers who feared projects in Beijing and Shanghai might never be completed. Now, Evergrande’s liquidity issues are affecting its customers in Hong Kong. On Wednesday HSBC Holdings Plc, Hang Seng Bank, the Bank of China’s Hong Kong unit, and the Bank of East Asia stopped providing mortgages to people who want to purchase Hui’s yet unfinished residential developments in the city.

If other cities in the mainland emulate Shaoyang, Evergrande will have to finish its projects quickly, and deliver the keys to consumers before getting paid. This, in turn, means Evergrande will have to work harder obtaining construction loans from banks, as well as smoothing out increasingly tense relationships with its suppliers. Both will be tricky. A few skittish banks have already decided not to renew their loans to Evergrande. The developer has missed a few payments on its commercial bills, a form of short-term payables to suppliers.

Meanwhile, how much cash does Evergrande really have at its command? China Guangfa Bank Co., a regional bank in Guangdong province, asked a court to freeze a 132 million yuan deposit held by the developer. The fear is that other banks and trust companies will also rush to stake a claim to Evergrande’s liquid assets.

The September scare was triggered by a purported letter to the government that pleaded for permission for a backdoor listing in Shenzhen to avoid a cash crunch. Evergrande said the letter was fabricated and was able to regain its footing after Hui convinced his pre-IPO investors — his long-time pals and suppliers — to take as equity about two-thirds of 130 billion yuan in hybrid securities due in January 2021.

This time, however, the credit scare is convincing banks and local governments to withdraw their support. How will Hui defuse this bomb? His poker club friends are, at best, stabilizing agents in Hong Kong’s capital markets. They can’t help with his business operations in the mainland.

With bankers and suppliers getting skittish, Hui will have to network among a much broader circle, perhaps proposing partnerships with fellow developers or even with state-owned enterprises — not the most selfless of allies. Whether or not he gets out of this bind will depend on Hui’s reputation. He’ll need more than friends.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.