Trump Has a Giant Wrench for China’s Auto Gears

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- To understand the untapped potential – as well as the dangers – of Donald Trump’s trade war with China, look at auto parts.

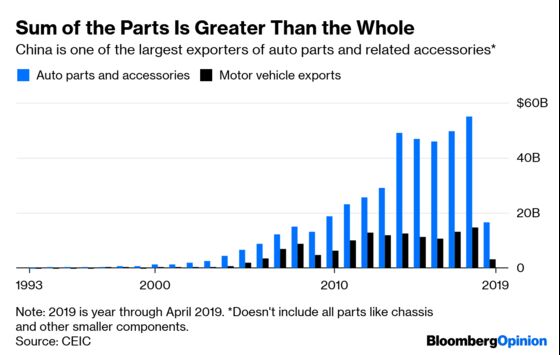

It’s a huge business, worth almost $400 billion globally. China exports more than $70 billion of car parts and accessories every year, about a fifth of which goes to the U.S. Hundreds of Chinese components, from door handles to steering systems, are embedded throughout American-made cars.

For a U.S. administration looking to exert pressure through tariffs, that might seem like a good place to start. Yet the sector is almost absent from the latest list of tariffs levied against imports from China, save for a few cheap products such as car-door hinges and radio receivers with clocks valued at under $40. Such low-margin parts are the least of China’s worries. Profits are increasingly concentrated higher up the value chain.

The sparing of auto parts shows the U.S.-China trade war remains far from an all-out conflict, illustrating how the optics of Trump’s tariffs are more alarming than the reality. There are high stakes in threatening disruption to the broader auto industry, as shown by the president’s decision this week to delay imposing tariffs on U.S. imports of parts and cars from the European Union and Japan.

China has been opportunistic in building up the industry. It reduced import tariffs on these goods last year, presumably as a show of goodwill but also because the value of U.S. auto parts exported to China is small. Chinese tariffs on imported parts went to 6%, from as much as 25% on body frames and 15% on axles. That’s helped to support manufacturers as auto sales drop and price competition intensifies. U.S. peers, meanwhile, are struggling with rising costs for raw materials (a result of Trump’s tariffs on products such as steel) and large-scale restructurings. In its latest round of tariffs targeted at the U.S., China excluded most auto parts barring a few items such as vehicle seats that are subject to the lowest level of duties at 5%.

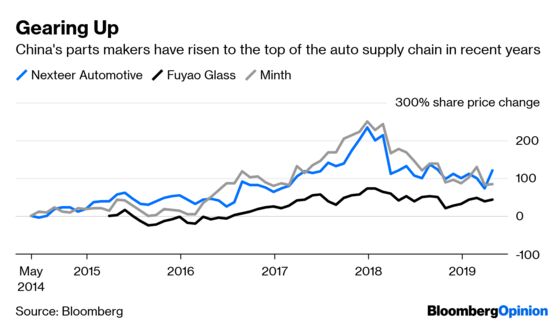

Sales to U.S. and other overseas car companies are a growing revenue stream for Chinese component suppliers such as Shanghai-based Huayu Automotive Systems Co. and Minth Group Ltd., which is based in the port city of Ningbo. Others, like Hong Kong-listed, Michigan-headquartered Nexteer Automotive Group Ltd., have operations in the U.S. and supply the likes of General Motors Co.

If Trump decides to target China’s auto parts industry, he won’t be the first. The sector is no stranger to trade crossfire, having been among the top targets for complaints at the World Trade Organization in the 2000s. The U.S., Canada and the European Union all filed cases at the WTO more than a decade ago. At one time, China’s tariffs on imported auto parts were so high that they could cost as much as a finished car if a manufacturer didn’t meet local content requirements. Other countries contended that this violated China’s WTO accession agreement.

China ultimately lost that dispute, its first such defeat at the WTO. However, it had already succeeded in changing the auto-parts supply chain, as carmakers switched to local component manufacturers and more foreign ventures set up in China. Those relationships weren’t reversed after the WTO ruling, with the country rising to become one of the world’s largest exporters of parts. More than a quarter of what it produces is shipped overseas.

In 2012, China faced another WTO complaint focused on export subsidies. The industry has managed to weather such challenges and keep growing, in contrast to the U.S., which has let its own auto-parts sector flail, as we explained here.

So far, the costs of President Trump’s tariffs on low-margin Chinese goods have been borne almost entirely by U.S. consumers, householders and importers, initial results from academic studies show. One paper estimated additional costs of $12.3 billion and a $6.9 billion decrease in real income in the first 11 months of last year. Domestic prices have risen and foreign exporters have absorbed almost none of the increase.

If Trump wants to attack an industry that actually matters to China, auto parts is an obvious target. The question is whether he’s willing to take the pain that this will mean for American carmakers and consumers.

--With assistance from Natalie Lung.

None of the tariffs go into effect immediately. From the U.S. side, there is a grace period of sorts based on a technicality (goods that left China and enter the U.S. before June 1 won’t be subject to the tariffs). China’s don't come into effect until June 1 and the commerce ministry has put in place a way to apply for exemptions. Essentially, despite the threats being lobbed between the U.S. and China, both sides have given each other time.

Completely knocked down and semi-knocked down parts kits.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.