Chile’s Problems Won’t Be Solved at the Ballot Box

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Investors in what has long been Latin America’s most stable economy should buckle up.

This weekend’s presidential vote in Chile looks likely to push into next month’s runoff a law-and-order candidate who admires General Augusto Pinochet and a leftist candidate harking back to Salvador Allende, whom the dictator overthrew in 1973. With moderates falling to the wayside, that outcome offers voters two radically different visions of the future, in a country still coming to terms with the double shock of 2019 protests and a pandemic. Voters will also elect parliamentarians, deciding just how much leeway to give the new leader. No one has the rulebook for what comes next: an ambitious new constitution intended to defuse popular anger will not be ready until well into 2022.

Chile, the world’s largest copper producer and a major lithium supplier, has for decades been a poster child for free markets and a haven in a turbulent region. Its sound macroeconomics and pro-business outlook have attracted more foreign direct investment as a percentage of the overall economy than higher-profile regional peers like Brazil. It has a lofty credit rating and one of the lowest levels of public debt among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a club of wealthier nations. Its Covid-19 vaccination campaign has been a success, and the government expects the economy to expand by more than 11% this year.

But the past is not necessarily prologue when voters demand change, the establishment has given way to centripetal politics and a new president and legislature will take over without clarity on the longer-term rules of engagement.

Clashes, even paralysis, seem inevitable in the near term, whichever front-runner pulls ahead.

Should ultraconservative Jose Antonio Kast prevail, his promise to cut corporate taxes and fiscal spending — doubling down on the country’s neoliberal credentials — sets up a clash with a lower house that a fragmented left looks likely to dominate. Vague plans to bring private capital into Codelco, the state-run copper behemoth, have already infuriated unions. Meanwhile, the other frontrunner, former student leader Gabriel Boric, backed by a coalition that includes communist allies, wants to raise the minimum wage and corporate taxes and replace the current private pension system, a pillar of Chile’s capital markets. His program is more of a European-style big-state than a Venezuela, but it’s still one he may struggle to fund or sell to investors, and which the right will fiercely resist.

Both sides have struck a more restrained tone as the race advances. Other candidates, like Christian Democrat Yasna Provoste, may yet break through. But the winner will also have to deal with a new constitution which could limit presidential powers and, if regional precedent holds, will almost certainly come with a long list of potentially unaffordable guarantees of socioeconomic rights.

Concern over spending — along with the prospect of further raids on the pension system to ease households’ economic pain — has already helped push up government bond yields and dragged the peso into the ranks of the poorest emerging-market performers. As Nikhil Sanghani of Capital Economics points out, fiscal policy is likely to remain loose whichever way the presidential race goes — whether with Boric’s larger state or, as is underestimated, with Kast’s promised tax cuts, which he may struggle to cover. And that’s before considering constitutional demands.

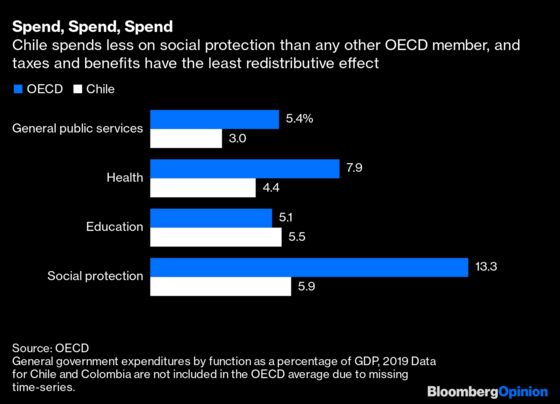

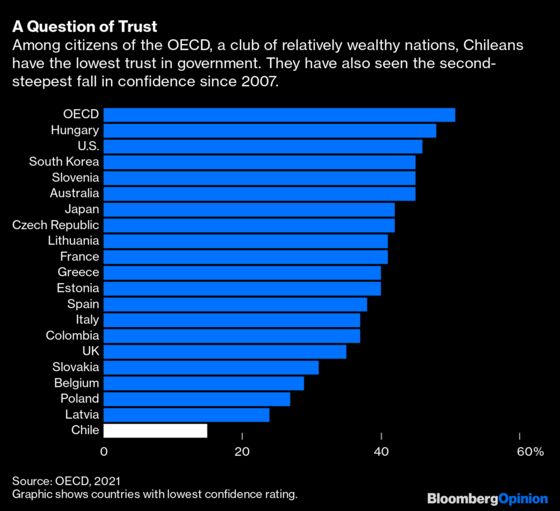

Chile’s aggressive neoliberalism created unacceptable inequality that the current tax and welfare system does too little to redress. Chicago-school economics brought faster growth and helped lower overall poverty, but fewer miracles than it is credited with; more than half of households are economically vulnerable, in part because higher-wage jobs are scarce, leaving much of the middle class dependent on precarious alternatives. Social mobility has faltered, and unhappiness with the quality of education, pensions and available healthcare is widespread.

Discontent, populism and politics pushed to extremes are not unique to Chile. The trouble is that adding to that mix the creation of a new constitution — drawn up by a gathering in which independents are heavily represented, after voters repudiated politics as usual — will not prove the institutional solution that some hope. Notwithstanding the problems with the previous iteration, with its roots in an autocratic regime, it’s unclear the benefits of starting afresh will outweigh the risks of a prolonged period of instability. In the near term, it will cast Chile into what Patricio Navia, political scientist and professor at New York University, described to me as a “valley of despair.” Writing a new charter, as he points out, comes with a high cost, given everything the country might lose.

Once written, by delegates chosen by less than half of Chile’s electorate, the document will have to be put to the public again.

None of this uncertainty necessarily condemns Chile to permanent structural deficits, or turns it into Argentina. A new social contract is urgently needed, public-sector debt levels are still manageable and the country’s neoliberal roots run deep.

But the risks around constitutionally mandated spending or even a larger state that crowds out much-needed private investment are real. Chile’s future may not be Venezuela, but it might resemble that of debt-burdened Colombia, or even Brazil: A little less miraculous.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.