America's Chicken Obsession Is Shifting to Dark Meat

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I sat down at an outdoor table at New York City’s Hudson Yards one bright May afternoon with a bag containing two of star chef David Chang’s entries in the fast-food fried-chicken-sandwich wars. They were both Fuku Spicy Fried Chicken Sandos, but with a crucial difference: one was made of thigh meat, the other of breast meat.

When Chang opened his first Fuku in 2015 at the site of his original, reputation-making Momofuku Noodle Bar in Manhattan’s East Village, it offered only thigh-meat sandwiches. Chefs and others who think a lot about food are nearly unanimous in their belief that dark chicken meat is juicier and tastier than white meat, and while Chang doesn’t always truckle to elite culinary opinion — witness his highly amusing pro-iceberg-lettuce Twitter rant that I had the honor of inspiring last fall — he is a self-proclaimed “dark-meat loyalist.”

But when Fuku expanded nationally last year, with delivery-only ghost kitchens in Baltimore, Dallas, Houston, Philadelphia and the Washington area, Chang & Co. seemingly wimped out. “As we have expanded outside our home market of New York City, our guests have asked for a white meat version, which ultimately inspired us to shift to a new sandwich recipe using chicken breast in 2020,” Fuku Chief Executive Officer Alex Munos recently told the trade publication Restaurant Business. The New York Fukus offer customers a choice, while outside the city Fuku is now an all-white-meat establishment. Which is why I trekked over to Hudson Yards, the new real estate development and high-end shopping mall on the far west side of Manhattan that is home to what is currently the world’s lone not-delivery-only Fuku, ready to eat a couple of fried-chicken sandwiches and expound on the perversity of Americans’ aversion to dark meat.

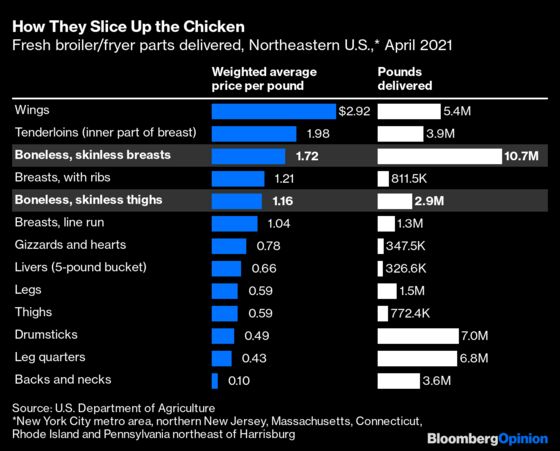

Yes, I, too, am a dark-meat loyalist. When I buy fried chicken, the pieces I want are the drumsticks and thighs. When I roast one it’s those plus the oysters or sot l’y laisse (a fool leaves it there), the nuggets of dark meat wedged into the chicken’s back next to the thighs that really are the best parts of all. When in preparation for my visit to Fuku I read Drew Magary’s early-2020 Eater essay arguing that the first major fast-food chain to use dark meat would win the fried-chicken-sandwich wars, I nodded in vigorous agreement. With the wholesale price of boneless thigh meat about two-thirds that of boneless breast meat in April, it seemed like a no-brainer.

Then I bit into the first of the sandwiches. I could tell immediately that it was made of thigh meat and thought, “this is pretty good.” The breast-meat sandwich, though, was a revelation — tenderer, crispier and more flavorful than its dark-meat counterpart. Its superiority probably had something to do with the 12 months that Fuku Culinary Director Stephanie Abrams spent developing it, and its 24-hour immersion in a habanero-pepper brine that seems to soak into white meat better than dark. It may also have been fresher: if customers are ordering more of the breast-meat sandwiches, they’re less likely to have sat around long before or after cooking. But I am now willing to at least contemplate that Chick-fil-A founder S. Truett Cathy wasn’t entirely wrong in opting for white meat in his trend-setting fried-chicken sandwiches, and that the nation’s fried-chicken-sandwich consumers aren’t necessarily missing out on a vastly superior alternative.

This is not, however, going to make me revise my opinion that dark chicken meat generally tastes better than white. And there are signs that, fried chicken sandwiches aside, my fellow Americans are finally beginning to come around.

How White Chicken Meat Triumphed

The modern chicken era in which Americans could eat their fill of cheap breast meat can be said to have dawned in 1923 when farmer Cecily Steele of Ocean View, Delaware, ordered 50 chicks to replenish her flock of egg-laying hens and was sent 500 by mistake. She decided to raise them for meat and sell them in Philadelphia as soon as they were big enough.

At the time, Americans ate about one-seventh as much chicken meat per capita as they do now, and almost all of that came from mature hens that had already been through a first career as egg-layers. That’s why Herbert Hoover supporters spoke in 1928 of “a chicken for every pot” — simmering a chicken for hours was one way to make it tender enough to eat.

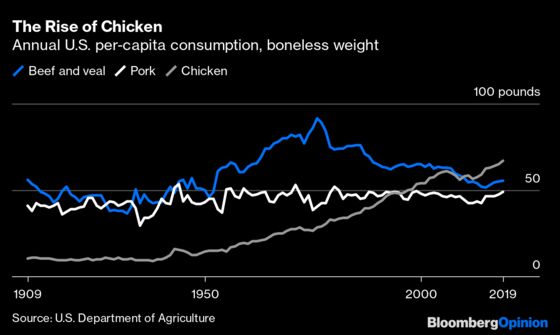

Steele’s young chickens were different and proved a big success. By 1926 she was raising 10,000 birds at a time, according to the National Chicken Council. Many imitators followed, and by 1952 such mass-produced young “broilers” had replaced egg-laying farm chickens as America’s main source of chicken meat. Generations of breeding have since resulted in broiler chickens that take less than seven weeks to reach an average live weight of 6.4 pounds, an unnatural amount of which is breast meat, supplanting beef and pork as Americans’ main source of meat.

Initially these broilers were sold whole, but profit maximization soon dictated a different approach as breast meat came to be valued more highly than the rest of the bird. One reason was the growing consensus among medical researchers in the 1950s and 1960s that consumption of darker, fattier meats led to heart disease. Another was the rise of a fast-food industry that for various reasons ended up favoring white chicken meat over dark. And yes, I guess it’s also possible that people genuinely thought breast meat tasted better, but I’m doubtful because (1) it usually doesn’t and (2) I’ve been reading the research into how consumer tastes are formed by marketing professors Bart Bronnenberg of the University of Tilburg in the Netherlands, Jean-Pierre Dubé of the University of Chicago and various co-authors, and buy their conclusion that people generally like whatever most other people around them liked when they were young.

The notion that red meat is worse for you than white meat has come under a lot of fire recently, with a team of researchers making headlines in 2019 with their conclusion that, after decades of studies, there isn’t persuasive evidence for it. There’s even less evidence that dark chicken meat is worse than white meat: it has more calories and fat per ounce, but that means it’s also more filling and less in need of, say, a cream sauce.

But the belief that white chicken was a superior, healthier product was still very much on the rise in the 1980s, which is when the fast-food industry began to fully embrace chicken. Kentucky Fried Chicken, which became ubiquitous in the 1960s, used lots of dark meat from the beginning for reasons of form as well as flavor — thighs and especially drumsticks are easier to eat with your hands than chicken breasts. But McDonald’s bone-free McNugget, rolled out nationwide in 1983, announced a new approach. (Chick-fil-A began breaking out of its initial home in shopping-mall food courts around that time, but remained a regional phenomenon.)

The original McNugget was not all white meat; it was an amalgam of breast meat, other bits of chicken and an array of other ingredients that later led a federal judge to dub it “McFrankenstein.” When Burger King unveiled its rival Chicken Tenders in 1986, it made a point of emphasizing that they were “real filets of all-white-meat chicken breasts, not formed bits and pieces of chicken like McNuggets.” And while McDonald’s didn’t switch the McNugget to all white meat until 2003, it was Burger King’s version that served as the template for the chicken fingers and chicken strips that became the fall-back food for picky eaters in restaurants and homes across the nation. If you don’t want to go the McFrankenstein route, chicken breasts are simply easier to slice into tenders/fingers/strips (and, for that matter, fried-chicken sandwiches).

Finding Somebody to Buy the Dark Meat

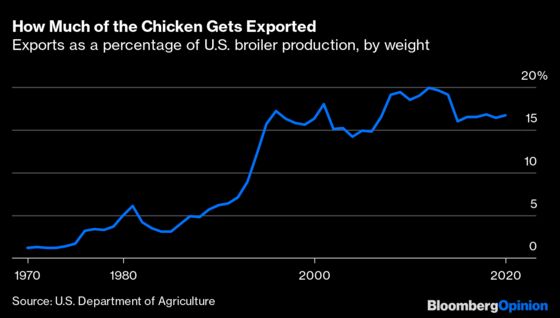

So as U.S. chicken consumption rose, the imbalance in demand for white meat versus dark grew as well. What to do with all that excess dark meat? Well, sell it to foreigners who hadn’t yet been talked into preferring white meat. (A colleague who grew up in India reports that when his mother brought home a chicken she would “chop it up ... and immediately give the breast meat to our dogs.”)

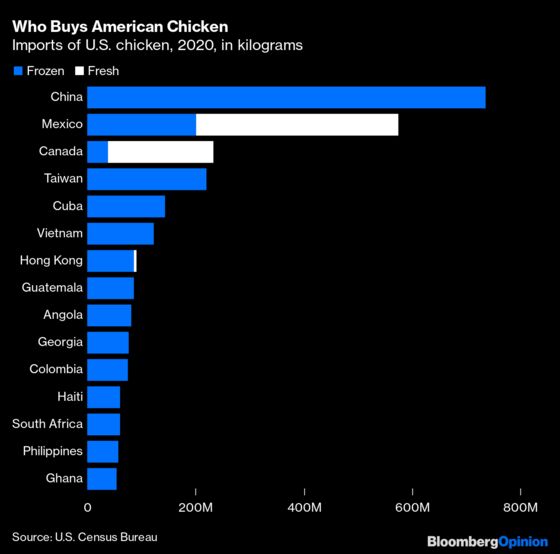

The first big overseas customer was Russia, which after the fall of the Soviet Union and subsequent partial collapse of Soviet agriculture imported huge quantities of cheap American chicken legs and thighs. Growing unease with depending on a geopolitical rival for sustenance led to the development of its own large domestic poultry industry, though, and Russia now exports about as much chicken as it imports, and imported none at all from the U.S. in 2020. China has stepped in as the top importer of American chicken meat, buying not just legs and thighs but also huge quantities of chicken feet (or “chicken paws” as they’re known in the trade statistics) that are consumed as dim sum and snacks. They accounted for nearly two-thirds of China’s chicken imports by weight from the U.S. in 2020 and 77% over the first three months of this year.

These recent figures are bit misrepresentative, in that China has also become touchy about American chicken, importing hardly any from 2015 to 2019 because of concerns about U.S. avian-flu outbreaks, which among other things caused billions of pounds of American chicken feet to be ground into animal feed or otherwise disposed of instead of exported. Western European consumers, meanwhile, are wary of the U.S. practice of disinfecting chickens with chlorine. The result is that a lot of America’s dark chicken meat ends up in countries not exactly known for their purchasing power, which implies that producers aren’t getting paid much for it.

Happily for the domestic chicken industry, Americans have begun buying more dark meat. “Deboned breast meat was really popular, and leg quarters pretty much a byproduct,” says veteran poultry economist Paul Aho. “What we’ve seen lately is deboned thighs have started to become more popular. People don't have as much fear of fat.”

This shift may have begun with the spicy Buffalo wing, which was invented in 1964 but went mainstream in the 1990s. Wings are technically white meat but served with the skin on they’ve got lots of fat, which is part of what makes them taste good. Thanks to the Buffalo wing, they have gone from cheap byproduct to the most valuable part of the chicken, with pandemic lockdowns sending demand and prices even higher. Leading purveyor Wingstop saw same-store sales rise 32% in the second quarter of 2020 and 21% for the full year, prompting multiple other restaurant chains to up their wing game. Even Chick-fil-A is adding wings to the menu at two new delivery restaurants it plans to open in Nashville and Atlanta. “Wing demand is extremely inelastic,” says Aho — if people want wings, they want wings, even if they have to pay extra.

Many restaurants do offer “boneless wings,” usually made of white meat, as an alternative, while Wingstop experimented last year with bone-in thighs seasoned like wings before deciding to stick with the tried and true. CEO Charles Morrison said in a February earnings call that the thighs will be “a product for the future” and that “dark meat in general” is “a great opportunity.”

Deboned thighs have been the main kind of dark chicken meat finding new restaurant uses lately. The product first became widely available in the late 2000s, and in 2008 and 2009 usually sold at a more-than-40% retail discount to deboned breasts. That gap has since narrowed, with boneless-thigh prices briefly exceeding boneless breast prices at several times over the past year. Aho says ethnic restaurants were among the early buyers, and Restaurant Business reports that chains from Chipotle Mexican Grill to Panda Express to Sweetgreen to Just Salad now serve deboned thighs too. Hot-dog chain Nathan’s Famous has recently opted to use thigh meat for its entries into the fried-chicken-sandwich wars, so we’ll see how that goes. Meanwhile, I cook up boneless thighs for dinner almost every week. They’re usually really good.

The biggest barrier to even more such thigh consumption seems to be the deboning process. Slaughtering chicken and slicing it into parts is largely automated in the U.S., which is why chicken didn’t face the same sort of supply shortages that red meat did early in the pandemic. But deboning is unpleasant, injury-prone manual labor, with thighs requiring more work for the amount of meat produced than breasts. Finding enough people to do this is a challenge even in a normal labor market, let alone the current very strange one, and while automated deboning is clearly the wave of the future it isn’t widespread yet. Shortages of deboned breast meat are currently making life difficult for some fast-food chains that serve chicken sandwiches and chicken tenders, but it’s not like deboned thigh meat is much more abundant.

Still, finding new ways to generate abundance is what the U.S. chicken industry has been doing for nearly a century. If we want more dark meat, we’re eventually going to get it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.