Biden’s Green Power Plan Is Good for Solar and Also … Bankers?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Democrats on Thursday night unveiled a key part of the climate agenda embedded in President Joe Biden’s proposed $3.5 trillion Build Back Better package. Here are some initial observations on the Clean Electricity Performance Program.

It’s complicated: The CEPP is sort of like a federal clean energy standard, forcing suppliers to raise the proportion of low-carbon power in the mix over time. Because it’s being pushed through budget reconciliation, though, the process is rather involved.

Essentially, electricity suppliers must raise the share of low-carbon power by 4 percentage points each year from 2023 through 2030. If they do that, then for 2.5 percentage points of that, they are granted $150 per megawatt-hour (except in 2023 itself, when it’s 1.5 percentage points). Fail to reach the 4 point threshold and they must pay $40 for each megawatt-hour missed.

This looks designed to augment existing state incentives rather than be a blockbuster replacement. That $150 should be thought of in the context of new clean-energy sources that run for a couple of decades or more; they aren’t getting that much per megawatt ad infinitum, as the baseline resets every year.

Having seemingly decided as a nation not to do the decent thing and just price the stuff we want less of (carbon), such convoluted carrots and sticks are what we get instead, and this is why we can’t have anything nice.

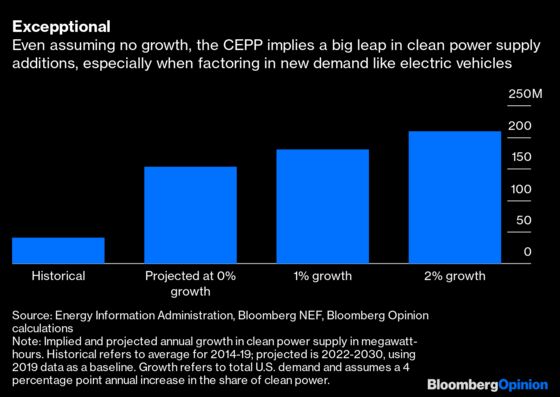

It’s ambitious: To say the least. Retail sales of electricity were about 3.8 billion megawatt-hours in 2019, of which 37% would meet the CEPP’s definition of “eligible clean electricity.” Using that as a baseline, and assuming no growth in demand, would mean adding an extra 150 million megawatt-hours of clean power supplied every year through 2030, taking the proportion up to almost 70%. By way of comparison, the average annual increment for the five years through 2019 was about 41 million megawatt-hours, inferred from Bloomberg NEF data.

Remember, though, that Biden’s agenda is predicated on electrifying most activities, such as transportation, so it implies overall demand rising rather than flatlining (it increased by just 0.2% per annum in the five years through 2019). The expanding baseline would make those 4 percentage points even more ambitious.

It’s terrible for coal, not great for gas, so-so for nuclear, spectacular for renewables: The CEPP defines clean power sources as emitting no more than 0.1 tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent per megawatt-hour. That is roughly a tenth of coal’s emissions intensity and one-quarter to one-third that of a combined-cycle natural gas power plant. Seems like the sort of thing that would give Senator Joe Manchin pause.

Moving on, it’s unlikely to spur investment in new nuclear plants. A grant of $150 per megawatt-hour on the first year’s output isn’t nothing, but it doesn’t transform a project supposed to last 30 years or more and with an estimated levelized cost that starts at $189 per megawatt-hour, year in, year out. Moreover, it’s highly doubtful you would get a single electron from a new nuclear plant this side of 2030, when the program ends.

That said, it could help keep existing nuclear plants open. That’s because closing one would then mean having to replace a big chunk of low-carbon generation even before trying to reach the 4 percentage point threshold to avoid penalties. The CEPP would act as an extra nudge alongside state-level incentives to keep reactors running, such as those that passed the Illinois House Thursday night.

Yet the current situation in California should temper enthusiasm. Besides the potential supply-chain pressures, building that much renewable capacity that quickly would require a concomitant leap in the deployment of batteries. And as the country’s de facto green leader is demonstrating, if those are slow to show up, then the fall-back involves burning a lot of natural gas to keep the lights on. Resolving that inherent tension inside of less than a decade is a monumental challenge.

It’s pretty good for bankers? As with all aspects of Biden’s climate plan, I tend to think the speed of the journey matters more than the ultimate destination. This is about harnessing and encouraging the existing shift in mood and, especially, investment flows toward a greener energy sector.

For example, the same day the CEPP dropped, a company that stores energy via the wonder of lifting and dropping giant lumps of concrete announced it would go public via — what else? — a SPAC, valuing it at $1.6 billion. One can only assume investors speed-read the description about blocks suspended on chains and thought this was a crypto play. In any case, that’s the mojo Biden’s after as he eyes future elections. This is less about getting to X percent of clean power in 2035, more about making sure his opponents can’t slam on the brakes in 2025.

Beyond the hosepipe of volume this would direct to equity and debt desks, the M&A types might benefit, too. When NextEra Energy Inc. reportedly made an offer for Duke Energy Corp. last year, one rationale was that NextEra could decarbonize Duke faster and cheaper than the company would on its own. In theory, the sweetener of the CEPP’s grants, rewarding rapid increases in renewable power deployment, might warrant such a deal being revisited.

Hugh Wynne, an analyst with Sovereign & Sector Research, raises an interesting wrinkle here, however. Since any CEPP grants awarded must be spent “exclusively for the benefit of their customers” — isn’t every utility dollar spent thusly? — state regulators may not allow a return on such investment. Wynne sees a potential parallel with the way investments funded with deferred taxes don’t earn a regulated return.

That said, avoiding the penalty may offer enough incentive to buy a carbon-heavy rival and speed up their emissions efforts. And given the grants can be invested in rebates to customers or further clean-energy projects (batteries?), regulators may look more kindly on such deals. If the physical infrastructure of the grid transforms at anything close to the pace envisaged by this plan — assuming it's enacted, of course — then the corporate landscape is bound to change, too.

This is inferred from Bloomberg NEF data for electricity generation (rather than sales)in 2019 of about 4.1 billion megawatt-hours, of which about 1.5 billion was derived from sources with emissions of 0.1 tonnes or less of carbon dioxide-equivalentper megawatt-hour.

This assumes the 4 percentage point increase in eligible clean power supply is met each year through 2030 and doesn't take account of potential penalties paid.

This capex estimate is derived from Bloomberg NEF's Energy Project Valuation Model, assuming a 100 megawatt tracking solar project taking two years to develop and build and beginning operation in January 2022. Does not include development costs. The grant assumes a 20-23% capacity factor and that the project qualifies for the full CEPP grant, adjusted by a factor of 0.625 (which is 2.5 divided by 4, to take account of the proportion of incremental clean power that gets paid).

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.