(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Defenders of free markets have always portrayed them as rife with healthy competition. Striving to outdo each other in providing high-quality products to consumers at ever-lower prices, according to this narrative, companies only profit from the hard work they do and the risks they take. This means that corporate profits should grow roughly at the rate of the economy as a whole. As for stock prices, they can grow faster than profits if investors’ appetite for risk increases, or if interest rates go down.

But skeptics of modern capitalism have an alternative narrative. Too many businesses, they say, extract value from the economy rather than add it. Using monopoly power, or favorable treatment from conflicted or ideologically friendly regulators, big corporations raise prices, push down wages and squeeze their suppliers to the benefit of their shareholders. Economists call this sort of value extraction economic rent.

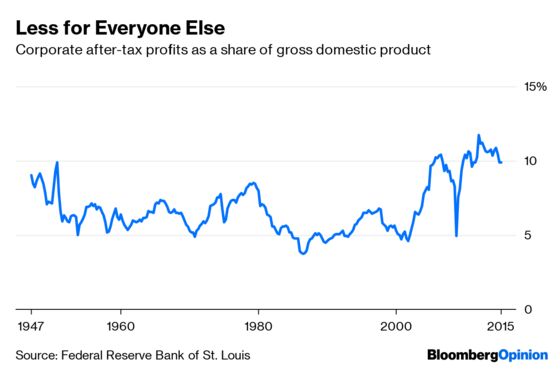

This is an important and timely debate, since during the past 15 years, corporate profits have taken in a historically large share of the value produced by the U.S. economy:

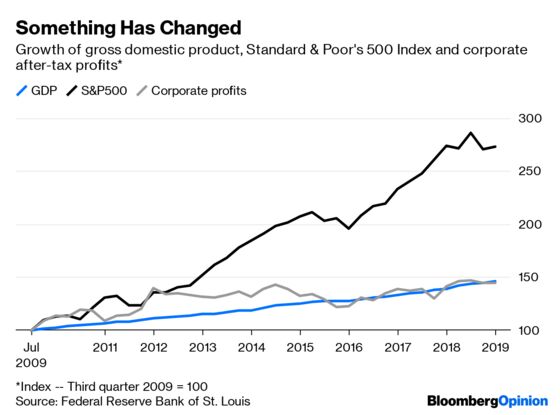

And in recent years, stock valuations have increased faster than either profits or the economy itself:

How much of this increase in market value was due to rent extraction, or to the expectation of future rent extraction? Economists Daniel Greenwald, Martin Lettau and Sydney Ludvigson believe they have an answer: Most of it. In a recent paper, they built a model of the economy in which the value created by businesses could be arbitrarily reallocated between shareholders and workers. They found that redistribution from workers to shareholders accounted for 54% of increased stock wealth. Falling interest rates, rising investor appetites for risk and economic growth comprised the remaining 46%.

Greenwald et al.’s result should be taken with a grain of salt, since it’s highly dependent on the assumptions of a very specific model. But their finding is consistent with evidence by economists Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman showing that labor’s share of income has declined all over the world. It’s also consistent with work by economist Simcha Barkai, who found that business profits have increased much faster than the value of the capital they own. When all of these different models find a similar result, it suggests that their conclusions are not completely illusory.

But this leaves the question of how shareholders have managed to extract increasing rent from the economy. In a healthy economy, competition should get rid of rents, because new companies will enter the market and vie for a slice of that pie, offering lower prices and higher wages until the rents mostly disappear. In some industries, like semiconductors, this still happens.

But in most industries, economists Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon believe, this process has broken down. In a new paper, they attempted to measure how much new business entry responded to the market opportunity available in an industry. Gutiérrez and Philippon used a measure called Tobin’s Q, which represents the ratio of a company’s market value to the book value of the company's assets. When Q is high, it should mean that new competitors have an opportunity to come in and take some of the profits in that industry, thus reducing existing companies’ price premium and bringing Q down. Indeed, the authors found that this was common up until the late 1990s. But after 2000 -- right around the same time that profits started to rise to unprecedented levels -- the relationship broke down. High Q levels no longer seem to attract new market entrants.

This might happen if returns to scale are increasing -- for example, if online companies such as Facebook and Amazon have network effects that keep out smaller competitors. But Gutiérrez and Philippon estimate that increasing returns to scale aren’t correlated with the breakdown of the relationship between Q and new business entry, casting doubt on this explanation. Instead, the authors point the finger at increasing regulation. They found that the higher the volume of new regulation in an industry -- measured by analyzing the text of the Code of Federal Regulation -- the less new entry is driven by high Q. They also found that lobbying expenditures in that industry are correlated with increased regulation, higher profits and lower entry. Unsurprisingly, they found that lobbying and regulation tended to keep out smaller companies to the benefit of larger ones. Gutiérrez and Philippon’s result fits with a similar 2016 finding by law professor James Bessen (though it contradicts a 2018 result by economists Nathan Goldschlag and Alex Tabarrok).

So it’s possible that big companies are increasing their market power by using lobbying to capture politicians and regulators. If this is true, it’s very bad news for free markets and capitalism. It would validate the claims of Senator Bernie Sanders, the socialist presidential candidate who has blamed corporate interests for the woes of American workers. Why exactly big companies and their lobbyists might have become more successful in bending regulation to their will since 2000 is still a mystery, but it’s a phenomenon that deserves more attention and investigation. The future of capitalism could be at stake.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.