The Big Question: Can the U.S. Prevent Another Crisis at the Border?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This is one of a series of interviews by Bloomberg Opinion columnists on how to solve today’s most pressing policy challenges. It has been condensed and edited.

James Gibney: President Joe Biden has suspended construction of the Trump administration’s border wall, but he’s also called for strengthening the border by improving technology and infrastructure at and between ports of entry. As the commissioner of Customs and Border Protection from 2010 to 2012, and the chief diplomatic officer at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) from 2012 to 2017, you know just how hard it is to deal with various threats — from terrorism and drug smuggling to irregular migration and now, pandemics. Is the U.S. Southwest border more secure now than it was four years ago?

Alan Bersin, Inaugural North America Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars: The principal reason why the issue of border security has been so contentious over the last generation of American politics is that we haven’t ever really agreed on what a secure border is. What does it look like? How is it measured? What dimension of security are you considering?

Regarding counter-terrorism, there’s been remarkable success since 9/11 in preventing the entry of terrorists into the country, through the use of big data and cross-border work with Canada and Mexico. With respect to unlawful or irregular migration, when President Barack Obama left office in 2017, we had reached the lowest level of irregular migration in decades. That then increased dramatically after President Donald Trump’s second year in office. Subsequently, the Trump administration substantially curbed irregular migration, by forcing—largely through threats of punitive action—Mexico and the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras to contain migration flows heading north. The imposition of public health controls during the pandemic then essentially halted the movement of migrants altogether across the border. The Biden administration’s approach to migration management likely will echo what occurred during the Obama years, for good and ill.

JG: What about on the narcotics side?

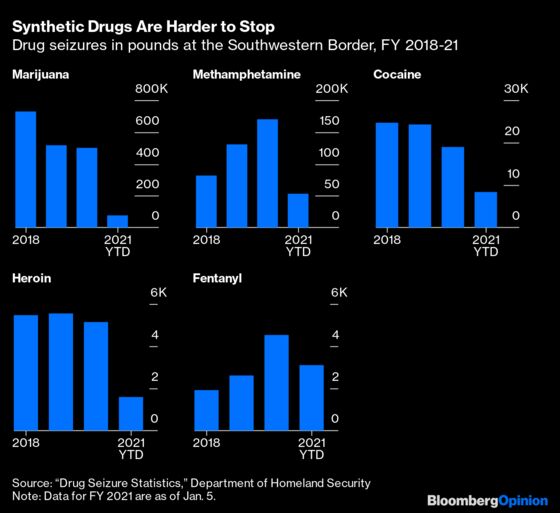

AB: That’s been the gaping hole in the border for the last 30 years that I’ve been watching it—and arguably, ever since President Richard Nixon declared the so-called war on drugs in the late 1960s. This vulnerability is driven by an insatiable demand for narcotics in this country. Year after year, despite increases in quantities of drugs interdicted, we never achieve a satisfactory effort to limit narcotics movement through the border, let alone seal it entirely. President Eisenhower used to say that when you can’t solve a problem over a long period of time, make it bigger. With regard to narcotics enforcement, we should look to levers of policy that are not at the borderline, and reconsider how we respond to drugs as law enforcement and public health issues. I think we’re in store for that kind of a reassessment as to how best to protect our people from the ravages of narcotics. We’ve lost the war on drugs in the way we’ve been fighting it for five decades and should own up to that fact. The deadly flow of synthetic drugs and precursors from China and India, often through Mexico, have only underlined this reality.

JG: So many people have seized on the border wall over the last four years as a symbol of what should or shouldn’t be done. Should some construction continue? Are there investments in barriers or technology and infrastructure that could make a significant difference that haven’t been made?

AB: For all the money and rhetoric that’s been spent and spilled on walls, only seven miles of new wall have been built during the past four years. Everything else done during the Trump Administration actually has been repairing or replacing existing barriers. This strikes me as consistent with the valid strategic role of barriers and fences—which is, to move cross-border traffic to areas where it can be detected and apprehended or interdicted more efficiently.

JG: Another critical issue is the development of a reliable entry-exit tracking system, something that Congress first mandated about 15 years ago. Will we have one by the end of Biden’s term?

AB: One significant area of progress at CBP during the Trump years has been the development and deployment of facial recognition technology. This addresses a problem that has bedeviled implementation of a viable entry-exit system for decades. Customs and Border Protection has introduced it in airport inspection facilities across the country and updated the database, enabling the use of big data to expedite travelers through checkpoints. This is going to become a major tool of border management once we can expand its effective use at land border ports of entry alongside airports.

JG: You recently wrote that “nation-states cannot successfully manage migration at the borderline of their territorial boundary itself. This boundary, the ports of entry situated on it, and the corridors between them are increasingly the last line of defense, rather than the first line of defense they traditionally have been considered.” What does a strategy that incorporates this redefined conception of a border look like?

AB: We need to move away from viewing borders solely as lines on a map or in the sand dividing one nation from the next, and analyze them as well from the standpoint of constant, often instantaneous, flows of goods, people, cargo, ideas, images—and electrons—that characterize the global era. We have to secure those flows moving toward the borderline by enlisting time and space, dealing with the issues as early in time before they arrive at the borderline and as far away geographically from the borderline as we can. In the case of irregular migration, for example, you shouldn’t wait for someone to come to the borderline to claim asylum or enter illegally. Instead, you should work as far away as you can to deter and prevent unlawful activity, partnering with Mexico and the countries of Central America to do so.

JG: What happens when your partners are problematic? Some of the things that Mexico’s President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has done, especially in recent months, suggests that the Biden administration is going to have some challenges ahead of it.

AB: Action by Mexico was the key to containing irregular migration flows from Central America during the Trump administration. The change in power in Washington has placed that relationship under the microscope. Lopez Obrador was slow to recognize Biden’s election, and the dispute over the arrest in Los Angeles of Mexico’s former Defense Minister for his alleged ties to drug cartels, and his subsequent release by the U.S. as a result of intense Mexican pressure, has jeopardized law enforcement cooperation going forward.

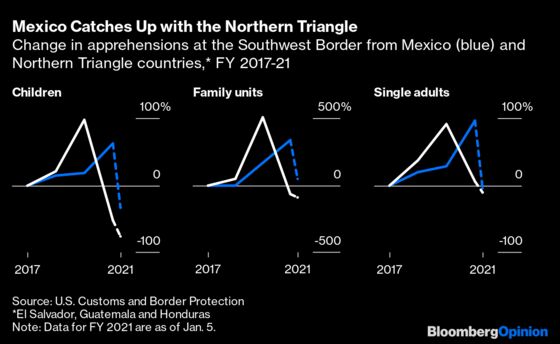

Nonetheless, Mexican cooperation on migration is likely to continue. First, after declining in recent years, more than half the migration now arriving across the border illegally is Mexican, given rising violence and the contraction of Mexico’s economy during the pandemic.

Second, something remarkable has happened in Mexico. As the Lopez Obrador administration moved to control Central American migration flows, contrary to what many Mexican opinion leaders and intellectuals thought, Mexican public opinion largely supported strict enforcement. Mexicans increasingly recognize that their country needs to control and discourage the flow of tens of thousands of irregular migrants through its territory. That shift will make bilateral cooperation easier over time with the United States.

JG: The Biden administration has put out a rough framework for working with Central America. To what extent will these initiatives differ from those that Biden helped launch as Obama’s vice president?

AB: One of the problems with the Obama administration’s development approach to Central America was that it was centered on traditional State Department programs — gang control, domestic violence counseling, etc. Don’t get me wrong: All of this is laudable. But this approach is long term and incremental and not going to change societies that are wracked by injustice, controlled by oligarchic families, and thoroughly corrupt for the most part. These governments are quasi-states rather than sovereign powers capable of protecting their populations.

If you don’t take on those fundamental issues, you won’t have much chance of developing those economies and protecting those societies and, therefore, countering the push factors that are driving people out of the Northern Triangle countries toward the United States.

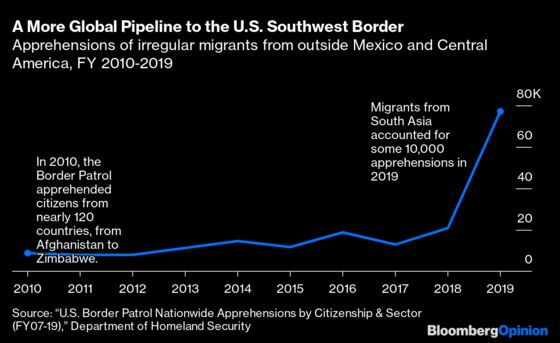

JG: One other problem that gets less public attention is the growing transit of irregular migrants via South America and up the isthmus to the U.S. southern border. How do you deal with that?

AG: Unless dramatic steps are taken, this “extra-continental” flow is going to add to a migratory problem that will explode into front-page news in the second quarter of this year and complicate Biden’s effort to deal with the pandemic, revive the economy and heal the political divisions that plague our country. In addition to the Mexicans that are coming in numbers that we haven’t seen since 2015, we’ll see a resumption in Central American migration, which is now about 36% or 37% of total apprehensions at the Southwest border. Mexicans are at 53%. The remaining 10% or 11% of irregular migration is what you were referring to. The largest group are Haitians, but it includes a wide range of people from outside the Western hemisphere, arriving from Africa or Asia.

Right now, the Title 42 health prohibition on admissions to the U.S. via ports of entry on the borders with Canada and Mexico remains in effect. That means that the way in which migrants will try to enter this country will be by crossing illegally with the help of smugglers. The only way you can deal with that issue is through cooperation with the transit countries, starting with Colombia and Ecuador at a distance, but then in Panama and up through Central America into Mexico. We have to build up regional mechanisms that haven’t been operating, in part because of the pandemic, but also because the Trump administration approach was based more on coercion and cruelty rather than cooperation.

JG: And even if those prohibitions are lifted, there will still be huge problems at the border because of the swamped and dysfunctional system for processing asylum cases, right?

AB: If you have tens of thousands of people at the border, even if you process them more effectively, you do not have the ability to detain them under governing judicial decisions and policies. This problem emerged at the end of the Obama administration, and nothing was done in the last four years to address its underlying causes. We need to reform the asylum system, which is not likely in the short term because of congressional impasse. But we also should be looking for alternatives to having large numbers of people come to the border, claim asylum and then be paroled into the country because of the lack of an effective immigration court system. The immigration system is broken to be sure, but no part of it is more broken than the asylum system.

JG: In effect, you’re talking about setting up processing centers in transit countries or source countries?

AB: Exactly, and create safe zones and places where people can be protected if they’re in need of protection. Those zones would also eliminate the incentive to abuse the asylum system by smugglers and by migrants who are leaving their countries primarily for economic reasons. But you need well-organized and resourced processing centers. The in-country Central American migrant processing program put into effect by the Obama administration took two-plus years to process applications. That can’t compete with a smuggling organization that promises to get a migrant to the border in four to six weeks.

JG: Let’s talk about a group of people who are responsible for dealing with this problem—your former colleagues at Customs and Border Protection. When you took the job as commissioner of CBP in March 2010, what was the biggest challenge you faced?

AG: In those days, it was counter-terrorism. We had the Christmas Day attempt to blow up a Northwest Airlines flight by the so-called “underwear bomber,” the Yemen parcel bomb plot, and other terror attempts. But even then, we also had the continued movement of irregular migration, mostly Mexicans coming up through the Arizona corridor, and we also were working hard to get trade issues back onto the agenda of Customs and Border Protection.

During the Trump administration, the Department of Homeland Security in effect was converted into a migration-only agency. All of its other missions were mostly ignored to focus on stopping legal and illegal migration into the United States. This politicization has done harm to the institution in many ways. It’s undermined what we thought had been accomplished in terms of professionalization across the board. So the first challenge is to restore the idea that partisan politics plays no part in law enforcement—at the border or anywhere else—and to remedy the huge deficit in public trust with CBP. The large majority of CBP officers and Border Patrol agents will respond, I believe, to a call to principle from a new committed leadership.

The second big challenge is that within 90 days or so, we will be facing a border crisis. We’re going to start to see smugglers bringing tens of thousands of Central Americans, in addition to Mexicans and Haitians and extra-continental migrants. Last month, we saw 78,000 apprehensions at the Southwest border. That’s far beyond what we have seen since May 2019 when the Trump administration did start operating away from the border to control migration. It was much higher than what we saw at the end of the Obama administration. If January was 78,000, we’ll likely see 90,000 to 100,000 apprehensions by the end of February 2021. We’re not prepared for that. Given the other challenges facing our country, whether with the economy, public health or politics, it’s going to be a messy time at the border.

JG: So what’s your bottom line? What should the U.S. do to improve security on the Southwest border?

AG: In terms of looking at border security as migration management, there are two critical dimensions: First, in the short-term, get your messaging correct. If you’re not very clear, smugglers will misinterpret and migrants will hear what they want to hear. The second is coordination with Mexico. We have to be sure that the essential steps that Mexico has taken will continue, or we will face the same flood of migrants at the border that we saw during the Trump administration in May 2019.

In terms of narcotics and border security, the immediate step is to improve our technology: better hardware for scanning and detection, but also the use of big data and artificial intelligence, and machine learning to target high-risk shipments. And in the longer term, we can’t solve the problem of narcotics without better public health strategies.

None of these problems can be dealt with unilaterally, much less just on our physical borders. We have to build up our relationship with Mexico, as well as a multilateral effort to promote change in Central America, develop regional systems to deal with asylum and migration enforcement, and step up our law enforcement cooperation beyond the borderline to beat the criminal groups that thrive on the market for drugs and illegal labor here in the United States and drive so much of the violence in Mexico.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

James Gibney is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. Previously an editor at the Atlantic, the New York Times, Smithsonian, Foreign Policy and the New Republic, he was also in the U.S. Foreign Service from 1989 to 1997 in India, Japan and Washington.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.