(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Andrew Yang, a former technology entrepreneur now running for president, has a compelling theory of what’s wrong with America. What he lacks is an equally compelling plan to address it.

Yang’s theory is essentially that Silicon Valley, by offering huge salaries to attract the best and brightest from cities large and small, is strangling the rest of the country. Actually, it’s even worse than that: Once they get to Silicon Valley, they set about creating technology that destroys jobs in their former hometowns. Yang is deeply worried, he says, about automation, and that led him to his most attention-grabbing proposal: something he calls the Freedom Dividend, a $12,000 annual grant to every American over the age of 18.

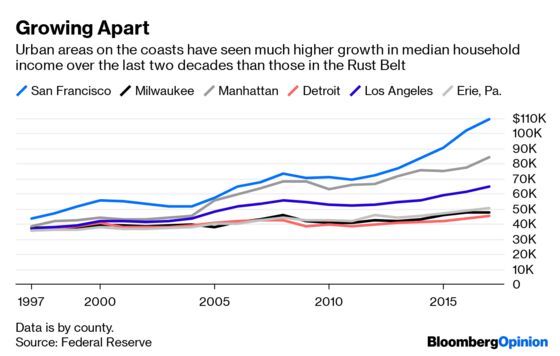

Yang is correct that, outside of high-skilled urban areas, wage gains and employment opportunities for many Americans have been frustratingly hard to come by. He’s also right that the persistent loss of manufacturing jobs has its origins in Silicon Valley and other places in the U.S., mostly on the coasts, with a large proportion of highly educated workers.

The problem, however, is not automation. It’s fragmentation. The U.S. economy is becoming increasingly geographically segregated, and economic policy that’s right for high-income urban areas is problematic for the rest of the country — and vice-versa.

Many areas of America, the Rust Belt in particular, would benefit from simulative economic policies such as lower interest rates and a weaker dollar. But those policies drive up asset prices and tend to produce bubbles in urban clusters. In the late 1990s, it was the dot-com bubble. In the mid-2000s, it was the housing bubble. When these bubbles popped, they produced huge losses in manufacturing jobs.

For the last several years, the Federal Reserve has been trying (and mostly succeeding) to chart a middle path — allowing the economy and employment to grow while also keeping watch for any possible bubbles.

But there is a fundamental tension between these two goals, and it has caused the U.S. job recovery to be slower than it might have been. This same tension also exists in the Eurozone, where the European Central Bank resisted adopting policies to repair the economies of peripheral countries such as Spain and Greece for fear of overstimulating the economies of the core countries such as Germany.

There is a solution to this type of problem: robust internal migration. If workers can easily move from low-income areas to higher-income areas, the tension is alleviated. In both Europe and the U.S., however, the workers who most need to relocate — those with few skills or job prospects — have the hardest time doing so.

In Europe, the barrier is often language. In the U.S., the barrier is often housing.

A combination of zoning restrictions and rent control make it hard for low-skilled workers to move to metropolitan areas such as Silicon Valley, New York or Boston. Zoning restrictions prevent the construction of multifamily apartment buildings, while rent control encourages landlords to turn apartments into condominiums. The result is that it is nearly impossible for new residents to find affordable housing.

In short, the problem isn’t so much that the best and the brightest are moving to Silicon Valley, as Yang says. It’s that they’re the only workers who can afford to. If lower skilled workers could also move, then employers in the rest of America would probably face a labor shortage and have to raise wages.

Now that the economic expansion has gone on for more than 10 years, wages are finally starting to rise. Yet this fundamental tension between high-income urban clusters and the rest of America persists. And when the next recession occurs — and it will — these geographic fissures will widen: Urban areas will recover relatively quickly while the rest of America won’t.

Yang is correct that the U.S. needs to act now to ease the tensions brought by economic fragmentation. And a freedom dividend would, theoretically at least, make it easier to for Americans to move, since it could be used a housing stipend.

But the underlying problem — restrictive local housing regulations — would remain. Among the more than 100 proposals on his campaign website, only one concerns zoning, and it is two paragraphs. That’s inadequate. Elizabeth Warren, Julian Castro and other Democrats have more substantive plans. Republicans also need to be more engaged, since free-market solutions, like permitting the construction of more market-rate apartments, will require Republican support.

Affordable housing may seem like a blue-state issue, but it affects the entire U.S. economy. It’s crucial that all Americans work together to solve it.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Michael Newman at mnewman43@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith is a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina's school of government and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.