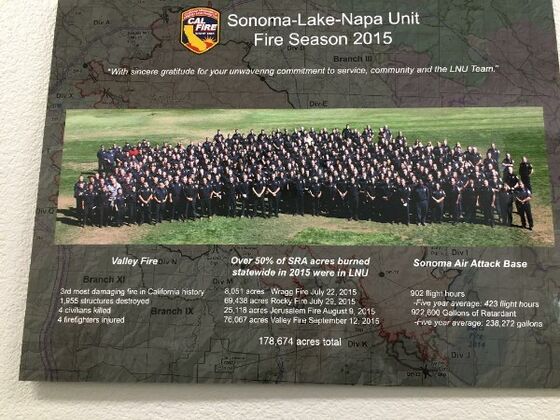

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Down the hall from Tom Knecht’s office in St. Helena, hanging on a wall near the reception area, is a memento from the Before Times: an official photograph of several dozen California firefighters in their dress blues, commemorating the 2015 fire season.

It was a memorable year for the Sonoma-Lake-Napa unit of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, commonly known as Cal Fire. The Valley Fire of September 2015 was the kind of experience that firefighters talk about for years, a “once-in-a-career event,” said Knecht, the unit’s division chief.

The fire traveled 11 miles in about 12 hours and burned 76,000 acres, destroying almost 2,000 structures, killing four people and putting four firefighters in the hospital for weeks. It was “the single most devastating thing the unit had ever seen,” Knecht said. “We thought, ‘We really need to remember this because this will never happen again.’”

Two years later, in October 2017, the Tubbs Fire ripped through Lake, Napa and Sonoma counties. Aerial images of the conflagration appear supernatural. It was the most destructive fire in California history. The next year the Camp Fire destroyed the town of Paradise, to the north, with a speed and intensity that seemed apocalyptic. Then the Kincade roared through in 2019, marking a new worst for Sonoma County.

The worst was still to come. A series of fires swept wine country beginning in August 2020, engulfing the region in smoke and flame for weeks. Residents who had survived the serial calamities of the past half-decade swore they’d never seen anything like the fires last year. Vineyard owners with expansive views of some of the most storied agriculture in the world could barely see past their swimming pools. Vineyard workers gagged just standing still.

In the American West since 2000, an area larger than California has burned. In California in 2020, more than 4 million acres burned. In wine country, according to the Santa Rosa-based Press Democrat, in the past six years there were 23 major fires totaling nearly 1.5 million acres, “the equivalent of 130% of Sonoma County.” Sonoma County is larger than Rhode Island.

The fires threaten both a way of life and a thriving, much-admired industry. Napa wine alone injects about $34 billion into the U.S. economy. Now the Michelin-starred life of Napa Valley, a rarefied micro-culture marked by affluence, natural beauty and the aesthetic alchemy that transforms farms into terroir, and grape juice into something else altogether, has been shaken. Relentless drought and fire have drawn down the wine industry’s boisterous confidence as surely as they’ve sapped the region’s water supply.

“Everybody in this industry knows somebody who ran for their life or who was directly affected, lost their home,” said James McDonough, founder of Wren Hop Vineyards in Sonoma. The wine industry in Napa, with about 45,000 acres under cultivation, lost an estimated $2 billion last year. Across Napa and Sonoma, wineries burned. Vineyards were scorched. Inventory was destroyed. Smoke ruined much of what remained.

This year, meanwhile, has been the hottest and driest yet. The air is like a desert breeze, leaving a sandy tickle at the back of the throat. The body requires constant hydration. Everyone dreads the impending return of fire season, which used to coincide with harvest in the fall. Now, some fear that the notion of a season is itself a relic of a bygone era when fire could still be contained.

***

The best agricultural land in California’s San Joaquin Valley can go for as much as $40,000 an acre. In Napa, prime agricultural plots cost more than 10 times that. Few start a vineyard in Napa or Sonoma to get rich; the margins in the wine business can be tough. The typical order of things is to get rich first, then realize a long-held dream of buying a vineyard. Some owners are dilettantes. Some are multinationals. Others come to wine country to learn and work, applying the same energy, ambition and competitiveness to winemaking that they used to power success in other fields. Many stay — entranced by the land, the work, the culture, the wine.

Soil, like expertise, is part of the equation. But the region’s temperate climate is key to its status as one of the greatest wine regions of the world. According to Napa Valley Vintners, the dry, Mediterranean climate that defines Napa prevails over just 2% of the earth’s surface.

The grapes that make the world’s greatest wines, said Eric Sklar, a co-founder of Alpha Omega winery in Napa, “grow in a very narrow band of latitude around the northern hemisphere, and the same around the southern hemisphere. Tuscany, Bordeaux, Burgundy, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, so on. Those grapes like very specific climate, which is hot, dry summers, plenty of water in the winter to refill the water table, and they like cool nights.”

Driving north on Silverado Trail, from the city of Napa to Calistoga, you can see the complex world that climate, artistry and entrepreneurship have built, where an ancient art rooted in soil is marketed, three-quarters of a liter at a time, to affluent consumers. Wine tourists dip in and out of vineyards for tastings and tours, or roam the two-lane roads in rented convertibles.

Nearing Calistoga, however, peripheral vision begins to cause discomfort. The withered leaves on that tree. That curiously disfigured branch. A blackened tree stump. Eventually, the charcoal-colored flora is too pervasive to ignore.

The driveway to Jones Family Vineyards, off Silverado Trail, is unmarked. But the scars of last year’s Glass Fire are visible every inch up the long, narrow driveway. Blackened trees lie horizontal across the ground, like felled warriors, on either side of the drive. A battle was lost here.

At the top of the drive is enough room to park beside an unblemished home, spared by the flames. Rick Jones was a McKinsey consultant and a supermarket executive before emigrating to Napa. He bought this land in 1993 and established his estate wine brand with his daughters in 1996. They produce fewer than 1,000 cases a year. Like many small operations in the valley, Jones Family Vineyards has cultivated a direct-to-consumer business for its sauvignon blanc and cabernet sauvignon, the latter of which currently sells for $150 a bottle.

The fire consumed about one third of the vines on the property, which has a commanding view of the Napa Valley and a more intimate perspective on the hillside destruction below the house. “We lost the first six or seven vines in every row down here,” Jones said, pointing to a slope beneath his home. “It’s unclear what will be the productivity of the vines.”

When you add up the fire damage to the 10-acre vineyard, Jones said, it reaches the high six figures. “We’re going to have to bear all the cost,” he said.

***

Fire, however, is not the primary source of wine industry pain. Smoke is. Vineyards that were miles from flames saw crops destroyed by smoke, which clings to grape skins and induces chemical changes.

Smoke taint produces toxic compounds. “Smoky-type compounds can affect vines at different growth stages,” writes Richard Carey in Wine Business. The danger grows as veraison — the ripening of the grapes — progresses. Yet even when you’re hunting for it, evidence of smoke taint can be hard to discern. To defend against the smoke’s toxic compounds, a vine “adds a sugar-type molecule to the offending compound, and that turns it into an innocuous, non-aromatic version,” Carey writes.

The industry is undergoing a crash course in the chemistry of smoke. Pre-fire and post-fire consulting and related services are robust growth industries. Testing labs were so backed up last fall that they couldn’t handle demand from frantic winemakers.

There is much still to learn. Grapes that test free of smoke taint can nonetheless produce wine that tests positive. And the exact quantity of taint that a vintage can survive is a matter of science, expertise and guesswork. “There’s so little that’s known about it,” said Joe Reynoso, a former derivatives trader who in the mid-1990s bought the Sonoma vineyard where he now produces Crescere Wines.

Much of the 2020 vintage in Napa and Sonoma was destroyed by vintners who couldn’t trust their own grapes. “At our co-op winery, we were supposed to bring in 1,500 tons of fruit,” Reynoso said. “We brought in 500.”

James McDonough, whose Wren Hop vineyard in Sonoma produces pinot noir, said smoke taint doesn’t produce a cozy “toasted marshmallow” affect. “It tastes like an ashtray.” When McDonough’s 2020 grapes were tested for smoke taint, they exceeded the recommended threshold. “For the first time, we were forced to surrender the crop due to smoke taint and high threshold detection,” he emailed. “Textbook bust.”

The pervasiveness of smoke and flame has not aided the wine industry’s standing with insurance companies, which was already a little dodgy owing to the vagaries of ultra-premium-priced agriculture. “There’s a crisis now among winery owners, because so many of us have been denied coverage with no alternative,” Reynoso said. California’s FAIR plan, an insurer of last resort, doesn’t cover many wineries, though legislation is moving to make it more accessible to the wine industry by covering “agricultural infrastructure.”

It’s not hard to see things from the insurers’ perspective. Napa and Sonoma winemaking are in the crosshairs of chronic drought and recurring mega-fire. An industry that depends on a carefully calibrated climate, adequate water supplies and complex soil composition is undergoing severe change. Last year was catastrophic. The current year looks frightening. It would be hard to make a case that everything is fine.

***

I am standing on Crystal Springs Road, just off Silverado Trail, repeating variations of the same dumbfounded query: How?

This area was already burning when Cal Fire set up a command post here on the morning of Sept. 27, 2020, when the Glass Fire roared down the hills toward Silverado Trail. (The fire is named for a nearby road.) Fire swept both sides of the road here, scorching trees and shrubs on one side, a field on the other. Justin Benguerel, a Cal Fire battalion chief, is trying to help me understand how a flaming ember could have been ejected from a nearby hill and sent sailing clear across Napa Valley on a hellfire of wind.

The valley is about 5 miles wide at its widest part, but perhaps only a mile wide here. Still, a mile seems a long way for an inflamed piece of wood to travel in the air. If the ember were small enough to travel that far, wouldn’t the rush of wind, and the duration of the flight, extinguish it? If it were big enough to remain flammable, wouldn’t it be too heavy to travel such a distance?

The morning of the Glass Fire, when Benguerel and his colleagues noticed that another fire had started a mile or so to their rear, they assumed it had ignited independently. “Some of our colleagues, myself included, could not wrap our heads around it,” Benguerel recalled. “We had about 30 minutes of denial.” They eventually concluded that the fire in front, and the fire behind, had the same source. (A subsequent Cal Fire investigation confirmed it.) The wind was so intense, and so hot, that a fire brand from the hill in front had shot all the way across the valley, where it ignited a fraternal blaze on a hill opposite. The discovery presaged a grueling battle, in which fire repeatedly leapfrogged those fighting it.

Some locals believe not only that Napa is hotter and drier than it used to be, but that the Diablo winds, which flow from the Sierra Nevada mountains in the east and arrive hot and dry in wine country, have gotten stronger and more sinister. Craig Clements, director of the Fire Weather Research Laboratory at San Jose State University, is skeptical. “Overall, we haven’t shown that the winds are increasing,” he said in a telephone interview. While recent years have seen more “wind events,” he said, “there’s also more focus on it because of the public-safety power shut-offs and the recent big fires.”

Fires at the scale and intensity that California has been experiencing create their own weather. A chimney effect feeds air into the fire, producing a feedback loop of intensifying heat and energy. The result can be a “fire whirl” or “fire tornado” capable not only of cooking an automobile like a flame-grilled burger, but actually flipping it too.

Fire research and management has become as topical as grape varietals in wine country. University departments in fire science are expanding. Natives who knew nothing of the subject a decade ago now routinely describe brush and vegetation as “fuel” while assessing the strategies and shortcomings of Cal Fire, one of the most experienced fire-fighting forces in the land.

***

Lisa Micheli is president and CEO of the Pepperwood Preserve, a 3,200-acre science project in Sonoma where scientists study climate, drought and fire. The preserve’s location is fitting if not exactly felicitous; Pepperwood has burned twice since 2017.

Micheli, an expert in hydrology and climate, has turned Pepperwood into a laboratory of regional climate change. “We instrumented the heck out of the preserve,” she said. Pepperwood has 22 weather stations to monitor micro-climates on the site, along with 77 soil sensors at various depths. Altogether, the preserve generates about 350 streams of data.

Pepperwood is a microcosm of an environment under siege. “When you get into fire modeling, you have to basically characterize the landscape condition. There’s two parts of that: There’s the fuel, and there’s the dryness of the fuel. Then there’s the wind. Then there’s the ignition, which is kind of the Russian roulette of the equation,” Micheli explained.

With less moisture in the landscape, fires ignite more readily. With more fuel, they burn faster and hotter. Firefighters speak of wildfire climbing a “ladder,” igniting low-lying brush and then jumping to small trees before ascending a Douglas fir or other tall conifers. The result is a giant wall of advancing flame.

The Tubbs fire of 2017 followed roughly the same path taken by a previous fire, the Hanly, in 1964. But between 1964 and 2017, development expanded dramatically as the wine industry, tourism and residential construction boomed. The differences between the two fires are notable.

The Tubbs was faster, and far more destructive. The Hanly Fire destroyed 108 homes. The Tubbs destroyed 4,651. While there were no fatalities from the Hanly Fire, at least 22 died in the Tubbs Fire.

Even amid drought, most fires are ignited by humans. Yet there is broad consensus that climate change is lending a hand. Long before the serial fires began in wine country, a 2003 report from the American Meteorological Society stated: “Despite pervasive human influence in western fire regimes, it is striking how strongly these data reveal a fire season responding to variations in climate.”

Many who spoke to me in Napa and Sonoma advocated prescribed burns, the practice of intentionally burning target areas. The goal is twofold: to enhance the health of the surrounding forests by clearing out junk growth, and to defend human habitats by eliminating nearby fuel. It’s hard to accomplish this over millions of acres, some of which contain residences. But the practice has a long history.

Researchers have concluded that prescribed burning was practiced for centuries by native tribes in both southern and northern California. “John Muir thought he was looking at a wilderness when he got here,” Micheli said. “He wasn’t. He was looking at a tended garden.”

Europeans banned native burning practices and introduced invasive grasses that are more flammable than native species. “What the eradication of fire does to this landscape, which is a fire-adapted landscape, is it allows the forest to become much denser,” Micheli said. “It allows Douglas fir in particular to invade our oak woodlands and our chaparral. It’s very hard to kill an oak, or redwood, with fire. It’s very easy to kill a Douglas fir with fire.”

A changed landscape is now being worked over by a changing climate. “This sort of hyper-arid, drought-dominated, high-fire regime is completely in line with what we projected,” Micheli said, “and it's happening where we projected it could happen.” Micheli says climate modelers had envisioned that such an environment might well prevail by the year 2100. They did not, however, expect to be living in it themselves in the year 2020. “We’re looking 2100 in the eyeball right now,” she said.

***

The problem in Napa and Sonoma is primal: too much fire, not enough water. Wine country has the misfortune of being in the avant garde of climate stress. (It may not always be drought; there’s actually a possibility that the region might evolve to become wetter than in the past.) But the wine industry, and the region it dominates, is wealthy, powerful and highly sophisticated. It can draw on enormous assets, including passionate support from millions of wine consumers. Climate policy takes place at state, national and international levels. But if there’s a local way to ease the existential bind, this place, so rich in natural gifts and human resources, might have tools to find it.

To succeed, the region will have to manage the conflicts that ensue from scarce resources. Napa County was sued this year by a group claiming the county was permitting too much groundwater to be pumped from wells, thus preventing the water from seeping back into the Napa River, where fish and other life are threatened. The California State Water Resources Control Board in June ordered reductions in the amount of water pumped from the Russian River, which flows by some of Sonoma’s most famous vineyards.

Vintners say that Cal Fire should devote more energy to preventing fires, rather than fighting them after they start. Cal Fire points out that it has limited human resources confronting millions of acres of dense tinder. Meanwhile, Cal Fire leaders express aggravation with vintners who hire private firefighters to protect select properties without coordinating with Cal Fire. And just about everyone gets angry at one or another of the multiple state and local agencies that heavily regulate land use in wine country.

Many conflicts are byproducts of individual, social or political efforts to meet the crisis. I encountered raw emotion during my conversations in Napa and Sonoma, but never apathy. And to a remarkable degree, the partisan war over climate change is mostly irrelevant here. The wine industry, dominated by rich White men, is a pretty conservative crowd. But questions of belief are superfluous now. Fire is at the doorstep; action is required.

Julie Johnson, proprietor of Tres Sabores vineyard in Napa Valley, purchased a pump and 1,000 feet of hose to turn her swimming pool into a fire hydrant. “I’ve got to do what I can do,” she said. She has backup energy on hand in case the power goes off during fermentation, which requires careful attention to temperature.

Vineyard owners across the region are using goat and sheep to munch the low-lying fuel surrounding their properties. The vineyards themselves are ideal firebreaks. Tidy rows of vines, evenly spaced and hydrated, usually stop a fire’s advance. Johnson’s household emergency plan is to meet in the middle of the vineyard.

Johnson has been making wine in Napa for four decades. She dry farms Tres Sabores, using only the limited water nature has allotted. Her wily, mature vines can still access moisture in the deep, rich soil of the valley. But without rain, drought will eventually prevail. Meanwhile, she anxiously monitors her vineyard.

Rick Jones is heading a committee of Napa Valley Vintners to work on fire mitigation and response. Of the roughly 550 businesses represented by the organization, about 50 have signed up to work on the committee. “We’ve had other committees that may have 5 to 15 members,” Jones said. “We’ve never had one that had 50. This is clearly a topic of great interest.”

***

Jennifer Gray Thompson became executive director of Rebuild NorthBay, a nonprofit designed to assist rebuilding and resilience in wine country, in January 2018. She had worked in local government in Sonoma, where she grew up, but had no previous experience in disaster recovery. She has acquired a lot in three years.

Seated at a conference table — a reclaimed tree — in her Sonoma office on a recent Sunday afternoon, she spoke for 90 minutes on climate, fire mitigation, forestry, the post-disaster role of FEMA, the ascendant “disaster industrial complex” lining up to pocket state and federal funding and much more. Arguably most important, however, is her understanding of the role of people like herself, who connect the various interests in the region and push and pull them into coalition so they can act in concert. (Thompson’s own board of directors is such a carefully-wrought confluence of interests that it could have been hatched in a political science lab.) She is identifying needs, and corralling funding to meet them.

The fires changed Gray, and motivated her. “It was terrifying,” she said. “But it was the most transformative experience of my life.” The Trump-era descent into tribalism had shaken her faith in her country, Thompson said. The fires revived her confidence, with survivors disproving “the notion that we don’t care about each other and that we are divided and that we are unhelpful and that we’re fighting for scarce resources.”

Organizing those people into a coherent fire-fighting (and perhaps climate-repairing) force is a tall order, and time is short. “I’m a high-school dropout who has a master’s degree. I’m not afraid of adversity,” Thompson said. “But I needed that testament to humanity and I got it.”

Ultimately, California’s wine country is engaged in a mission that proceeds the world over: securing the claims of posterity against a mounting threat. A vast array of resources is being summoned to wage the fight. California Governor Gavin Newsom in May announced a plan for 1,400 additional hires at Cal Fire and an extra $2 billion for emergency preparedness, including fuel reduction and firefighting equipment.

At some of its highest peaks, the wine industry is a dynastic endeavor, with vineyards handed down through generations. The Antinori family of Italy (which has an outpost in Napa), traces its winemaking to the 14th century. Napa families seek to build dynasties too.

My last meeting in Napa was at Chappellet Vineyard and Winery with Dominic Chappellet, who manages sales and marketing for Chappellet wines. His parents were Napa visionaries, taking the wealth his father, Donn Chappellet, had acquired through a vending-machine business in Los Angeles and ploughing it into a 320-acre parcel on the isolated slopes of Pritchard Hill, off Sage Canyon Road.

“We were the first ones up here,” said Chappellet, who grew up on the vineyard his parents bought in 1967.

I had been to this place once before, as a tourist. But it seemed different on this quiet June morning. We were seated at a picnic table beside rows of chenin blanc as a cool breeze pulled across the hill and the sun rained down with all the glorious excess that is California. The silent vineyard, ruffled by the breeze, was achingly beautiful.

“The winery, the wines, these vineyards — they are what allow us to have this place,” he said. “Place is, for me, bigger than the wines.”

Chappellet lost about half its grapes to smoke last year. The vineyard has contracted with private firefighters to safeguard the property, which is likely too remote to be readily defended by Cal Fire if a voracious wildfire approaches. In late June, the family convened a meeting with neighboring vineyards to discuss coordinated mitigation and response. On the other side of Prichard Hill, the Chappellets have dug a firebreak.

Dominic has five siblings. There are Chappellet grandchildren and great-grandchildren. A rich family legacy, more than half a century old, resides here. But its perpetuation is threatened. It’s unclear if the vineyard and the winery, or even the land in its current sublime state, will be around for the next generation. When I asked Dominic if he thinks about that, he didn’t hesitate: “Every day.”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Francis Wilkinson writes about U.S. politics and domestic policy for Bloomberg Opinion. He was previously executive editor of the Week, a writer for Rolling Stone, a communications consultant and a political media strategist.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.