Inside the Battle for California’s Sports Betting Riches

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Sonoma County sunsets transform the greens, russets and yellows of a 68-acre vineyard in Windsor, California, into a portrait of bounty. To the east, in the foothills of the Mayacamas Mountains, a gated community features a Jack Nicklaus-designed golf course. Across Shiloh Road to the north, more modest homes abut an equestrian center. Jets overhead transit through a regional airport named for “Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz. The Kendall-Jackson Wine Estate down the road offers bocce, picnics and pinot noir.

At the end of a long driveway stands a mansion recently occupied by the vineyard’s owner — before he sold the spread for $12.3 million to the Koi Nation. The Koi, a tribe whose ties to the region date back thousands of years, intend to build a casino resort here.

The tribe envisions a $600 million, 1.2-million-square-foot development that will include a 200-room hotel, six restaurants, a spa, a conference center — and a casino large enough for 2,500 slot and gambling machines. It is to be the third Native American casino in Sonoma. The other two are River Rock, a small, forlorn slots house perched on a bluff near Geyserville since 2002, and Graton Resort and Casino, a sleek, Vegas-worthy operation south of Santa Rosa with several restaurants and a large hotel that opened in 2013.

Unveiled in September, the Koi project came as a surprise to local residents and politicians. They understand that if the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs allows the tribe to place the Shiloh Road vineyard into a federal trust, it will be free to do almost whatever it wants with it. Many are nevertheless prepared to oppose the casino; several “NO CASINO” signs have been hung from the fence surrounding the Koi’s vineyard. Local residents also concede that their homes, businesses and wineries occupy land long ago stripped from Native American tribes.

“The people who will be most affected are the neighbors, and they will be vocal,” said Sam Salmon, Windsor’s mayor. “People will say, ‘Stop it.’ But I don’t think you can. We’ll do as much investigation as we can. It could affect the town detrimentally.”

Salmon has participated in earlier contentious negotiations with local tribes and remains sympathetic to their needs and prerogatives. “We have to be reasonable,” he said. “It’s always drugs, crime and prostitution when people criticize casinos. But I don’t think that it will get so bad that it affects the life of the town.”

Some of the most pointed criticism of the Koi comes from another tribe that has already cashed in on casino gambling. The Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, who own the Graton Resort, accuse the Koi of making “an egregious attempt at reservation shopping” in Windsor. “This attempt by the Koi Nation to manufacture a connection to Sonoma County is an affront to Sonoma County tribes such as our own, who have an extensively documented presence here,” Greg Sarris, the tribe’s chairman, said in a news release. “This effort ignores federal law requiring restored tribes to demonstrate a significant historical connection to the lands on which they propose to game.”

Sam Singer, a spokesman for the Koi, argues that the tribe has deep historical roots in Sonoma, and says it unsuccessfully tried to partner with the Graton federation on the new casino. He says he remains “confident” that his tribe “meets or exceeds the requirements for gaming on this site.”

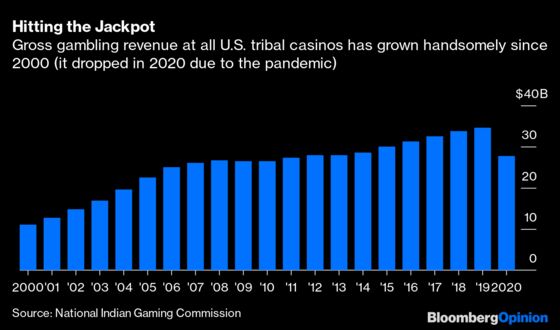

This clash may have less to do with the tribes’ historical legacies than with modern, ruthless business competition — and control of gambling riches. It’s also a reminder of how important wagering is to tribes nationwide. California is the biggest Native American gambling market in the U.S., with five dozen tribes running 66 casinos that together generate annual revenue of about $8 billion.

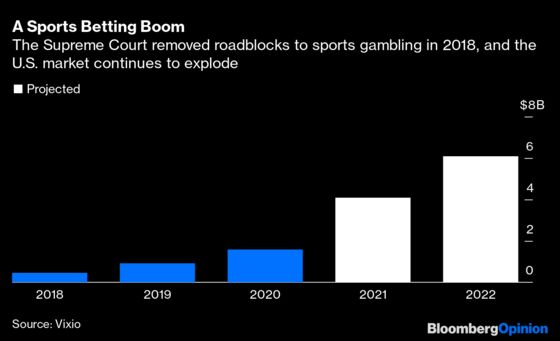

Hovering over all of this, too, is America’s sports gambling boom. Thirty states already have legalized sports betting, most of them in the past three years. California has been a holdout. But tribes — the Graton federation among them — are primary sponsors of one ballot measure seeking to legalize sports betting in the state. If voters sign off on the idea next November, California will quickly become one of the country’s most lucrative sports betting markets. Tribes want to control that business — or at least ensure they wind up with the biggest piece of it.

The scramble to dominate California’s gambling business reflects similar dynamics in other states. Legacy operators with brick-and-mortar casinos — whether they’re Native American tribes or publicly traded Las Vegas corporations — worry that online sports betting offered by digital impresarios such as DraftKings Inc. and FanDuel Group Inc. might undercut their business. And sports gambling is expanding so rapidly, shredding the legal and social boundaries that once constrained its growth, that towns, states, politicians and regulators have only begun to face the challenges it will bring. California stands to demonstrate for other states how gambling will evolve in the internet era.

The nationwide surge in digital sports gambling — reflected in the betting lines and ads that now scroll across TV screens during games — is making wagering far more ubiquitous and accessible. As cryptocurrencies mature, they may reshape how and where wagering takes place. One crypto exchange recently proposed letting casinos trade futures based on the outcomes of National Football League games. (It eventually withdrew the idea under regulatory pressure.) Professional sports leagues and media companies that once shunned gambling now boast about the lucrative partnerships they’ve formed with sports betting franchises. Investors are rubbing their hands as well, causing the market capitalization of sports betting upstarts such as DraftKings to soar.

California’s tribes understand the changes ahead. That’s why 18 of them joined the Graton federation to sponsor the legalization push. Their ballot measure would permit sports gambling only in the state’s casinos — an attempt to keep digital companies and other outsiders at bay. Competitors have responded by introducing measures of their own.

One of these, the California Solutions to Homelessness, Public Education Funding, Affordable Housing and Reduction of Problem Gambling Act, is backed by card rooms in the state and seeks to legalize online and mobile sports betting. Under this measure, everyone would be able to get in on the action: tribes, cards rooms, racetracks and professional sports teams.

Another competing measure is the California Solutions to Homelessness and Mental Health Support Act, backed by DraftKings, FanDuel and two other out-of-state gambling companies, Bally’s Corp. and BetMGM. This one also seeks to legalize online sports betting, but it would require operators to partner with a Native American tribe — a concession meant, presumably, to persuade California tribes to stop opposing digital wagering. The DraftKings coalition says it intends to spend $100 million to get its measure passed and has hired a onetime adviser to former Governor Jerry Brown to help.

Native Americans aren’t, like their competitors, billing their sports betting push in the Golden State as a panacea for homelessness, mental illness or public education. Their ballot measure is simply and bluntly packaged: “California Legalize Sports Betting on American Indian Lands Initiative.” Even so, tribes nationwide have a track record of good works and have regularly used gambling riches to fund schools, better health care, and new businesses on and off tribal lands. Sarris makes note of those benefits, as well as the operating expertise the Graton federation has gained running a casino, when he proselytizes for sports gambling.

“When it comes to sports betting and online betting, we have proven that we are good and smart people in this business and can do it well and can regulate it well,” he told an interviewer earlier this year. “We could revenue-share, as we do with the state. It could be a win-win.”

But gambling is never pure win-win. The tribes that have prospered from casinos are located near major metropolitan areas. Many living in rural or exurban areas still struggle with crushing poverty. Institutionalized wagering also typically generates higher rates of crime, personal bankruptcy, prostitution and compulsive gambling — alongside such benefits as increased employment — regardless of whether tribes, corporations or states run it. Although most people wager casually, and only a small percentage historically have been compulsive gamblers, the gambling industry appears to draw a significant chunk of its revenue from problem gamblers.

When California’s voters weigh in next year, they will need to decide whether they want sports betting at all and, if so, what role they would like tribes, Las Vegas veterans and new online companies to play in it. And as the largest expansion of legal gambling in the country’s history continues, these issues are going to gain traction in Indian country, wine country and everywhere else.

U.S. Representative Jared Huffman, a California Democrat whose district includes Sonoma County, said he considers the Graton federation a good corporate citizen, running its casino well and engaging with the local community. But he thinks the Koi’s project may encounter resistance from the federal government, even if other tribes have shown that gambling offers a path to economic development. And the possibility that any tribe or corporation might add momentum to the sports betting boom concerns him.

“I’m a sports fan and a former athlete. I think it’s an invitation to corruption,” he told me. “People want to address historical injustice. But is this a legitimate way to do this?”

Roughly 10 million indigenous people lived in America before Europeans began exploring the region more than 500 years ago, and what is now the Napa Valley and Sonoma County was home to about 35,000. Over the following centuries, tribes were forced onto barren reservations or decimated by disease, war and what California Governor Gavin Newsom recently described as “genocide.” The first governor of California, Peter Burnett, who hailed from a slave-owning family, was even more direct. “A war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct,” he said in 1851, shortly after the Gold Rush spurred land grabs and waves of murder and violence targeting northern California tribes.

In the decades shortly before and after the Civil War, local militias and federal troops massacred thousands of Native Americans in what later became wine country to make way for White settlers. In present-day Lake County, ancestors of the Koi rebelled against White colonizers who had enslaved them. U.S. troops slaughtered hundreds of them.

Ancestors of the Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo tribes, who later combined to form the Graton federation, were originally forced off their land and into what often amounted to slavery in the Spanish mission system. After White settlers and militia forced out the Spanish, the U.S. government formalized the expropriation of the Koi, Miwok, Pomo and most other tribes by passing legislation in 1861 that dissolved nearly all Native American claims to land in California.

A decade later, the federal government said tribes nationwide would no longer be considered sovereign nations but wards of the state — with a mandate to forcibly assimilate them into a White America. Almost a century later, in the 1950s, the government reversed itself again, adopting a “removal and termination” policy that ended tribes’ ward status and sought to move them from reservations into cities. Some tribal members ultimately returned to reservations while others subsisted in urban squalor — with double-digit unemployment, high dropout rates and short life expectancies. After decades of Native American activism, the U.S. passed a law in 1975 that reinstated tribal self-governance and autonomy.

Activism on California reservations also opened the door to casino gambling. In the mid-1980s, two California tribes appealed a state court ruling that bingo and card games offered on reservations violated state gambling regulations. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ruled that states lacked the authority to regulate gambling on reservations as long as state law sanctioned other forms of gambling (including state-sponsored lotteries). This triggered a gambling explosion on reservations nationwide.

Over the following decades, billions of dollars flowed onto some reservations — most notably, the Pequot tribe’s Foxwoods Resort Casino in Ledyard, Connecticut, and, more recently, the WinStar World, a 400,000-square-foot tribal behemoth run by the Chickasaw Nation in Thackerville, Oklahoma. The casino at the Graton Resort in Sonoma is modest by comparison — it’s only 135,000 square feet. But it was never supposed to exist at all.

When the Graton tribes sought federal recognition more than two decades ago, they said they were not planning to open a casino, but only wanted land to call their own. A few years later, they changed their minds and began scouting casino locations around Sonoma. The Graton Resort opened in 2013, financed through a partnership with a Las Vegas operator, Station Casinos LLC.

The Graton Resort doesn’t disclose its earnings but, shortly after opening, it projected annual revenue of about $500 million. The place earns enough to pay at least $8 million a year in local fees to offset tax payments it isn’t required to make. And it has paid tens of millions into a state fund that supports other tribes. Earlier this year, the resort paid off its development loans from Station and ended its contract with the company.

Today, the Graton Resort is one of the largest private employers in Sonoma and, prior to the Covid-19 lockdowns, said it attracted about 10 million visitors annually. Local concerns that the casino would exacerbate crime and traffic congestion have proved overblown, though critics say personal bankruptcies and prostitution have surged. Local authorities consider Graton to be a conscientious corporate citizen. And the tribes themselves have used their economic windfall to improve their lives and flex their political muscle in state and national politics.

“Indian casinos make more money in this country than the entire Hollywood entertainment complex,” Sarris, the federation’s chairman, said in a speech several years ago. “You know what that money means? It means self-reliance.”

But a pair of threats may eventually imperil — or at least impair — the federation’s financial self-reliance: the Koi casino proposal in Windsor and the advent of ubiquitous, digital sports betting.

Native Americans stand to become so central to sports gambling that the University of Nevada at Las Vegas recently offered a mini-course in how to go about “Choosing a Sports Betting Partner in a Tribal Environment.” In 2020, the university’s law school set up a new program focused on gambling and governance on tribal lands. The San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, which operates a casino in California and is among those pushing to legalize sports betting in the state, seeded the program with a $9 million grant.

But sports betting won’t need tribes’ help to continue expanding. The Supreme Court opened the door to the current sports betting boom in 2018 when it struck down a federal ban on sports wagering that had essentially limited it to Nevada. Well before that ruling, the internet had begun revolutionizing gambling, freeing it from the constraints of borders and buildings.

The sports betting market, currently $900 million a year, could grow to about $39 billion by 2033, a Goldman Sachs analyst recently estimated. As the market matures, about 50 million people may be betting on sports in the U.S. California alone could become a $3 billion market, according to Eilers and Krejcik Gaming LLC, a research firm that has advised state legislators on gambling policy.

The size of the California sports betting market — and the question of whether tribal casinos will control it — has apparently left the Graton federation on edge. In addition to the casino-based legalization measure it has already put on next year’s ballot, it is reportedly pondering introducing a separate measure — to allow digital sports betting as long as tribes have exclusive control over it. There’s precedent for this idea in Florida: The Seminole Tribe recently cut a revenue-sharing deal that essentially gives it monopoly control over sports betting in that state, whether on mobile platforms or inside brick-and-mortar casinos.

Legal challenges to Florida’s deal with the Seminoles have already arisen, particularly around digital wagering, because it’s not clear whether tribes anywhere are authorized to offer mobile gambling. Federal regulation and state compacts with tribes may need to be updated. In the meantime, the Graton federation and Windsor’s residents are keeping an eye on the Koi, who need approval for their casino from the federal government — a process that may take years, if it happens at all.

“If you build a casino at the edge of town in what was supposed to be a green-belt area, you undermine the family feeling all of us in Windsor have worked so hard to create,” said Deborah Fudge, a member of Windsor’s Town Council. “At a minimum, this will take a very long time — much longer than I think the Koi realize. A lot of people here think someone else is using the Koi to get a casino, but nobody knows who that is.”

The Koi declined to discuss with me how they raised $12.3 million to buy the vineyard along Shiloh Road, or to disclose whether they have partners.

Fudge conceded that the Graton federation had done well by its casino and community, but pointed out that the Koi resort would be in a very different location. She also said she had no idea that the Graton tribes were deeply involved in legalizing sports betting in California.

“Betting at that level harms communities and families,” she said. “I think more corporatized sports betting would just add more stress to everything.”

Stressful or not, sports betting is in the U.S. to stay, and California may end up showing other states how it will roll out at scale. Gambling enterprises, regulators, legislators, towns and families will be forced to adapt — and learn how to mind their markets, wallets and well-being.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Timothy L. O'Brien is a senior columnist for Bloomberg Opinion.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.