(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Senate Bill 50, which would force California localities to allow denser housing close to transit and jobs, died this week in Sacramento. It was a weird sort of death, with 18 state senators voting for it and 15 against on both Wednesday and Thursday. Six nonvoters kept it from the 21 needed to pass (if you’re adding this up and scratching your head, it’s because there’s currently one vacancy in the 40-seat Senate). An end-of-the-month deadline means it can’t be brought to another vote.

But when it was all over Thursday, Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins, a Democrat from San Diego, stood up (I was watching the livestream on my computer) and calmly declared that it really wasn’t. “This is not the end of this story,” she said. “SB 50 may not be coming up right now, but the status quo cannot stand.”

I get the sense she’s right about that. When San Francisco Democrat Scott Wiener started his quest to override local zoning rules, first with a bill called SB 827 in early 2018, then with SB 50 when a new legislature met that December, it got praise from housing wonks around the country but seemed to strike most Californians as an entirely alien idea. Wiener is a self-proclaimed progressive, but his plan was deregulatory in nature and a seeming boon to real estate developers. Affluent suburban homeowners complained that it would turn their neighborhoods into apartment-building-filled “Wienervilles”; less-affluent urbanites worried that easing development rules would displace them.

Since early 2018 the legislation has changed a lot to address those concerns, with exemptions for less-populous counties, leeway for local officials to propose alternatives for addressing housing shortages, and provisions to discourage displacement of existing tenants. Attitudes about it have changed a lot, too. In one poll of Bay Area residents this month, 68% said they supported the aims of the bill. As already noted, the leader of the Senate is a supporter. The governor and the Assembly speaker haven’t endorsed all the specifics, but seem on board with the general idea.

Then again, at least a couple of the people who voted “no” in the Senate said they were on board with the general idea, too. Agreement that California needs lots more housing hasn’t been enough to get something like SB 50 passed, at least not yet. But other changes made by the legislature over the past few years to allow homeowners to carve new dwelling units out of their houses and build backyard “casitas” have already spelled a de-facto end to single-family zoning in the state. And the simple fact that most California politicians now feel obliged to at least give lip service to the need to build more housing in major metropolitan areas in itself marks something of a political revolution.

California’s last political revolution around housing came in the 1970s, when local slow-growth and open-space ordinances began putting an end to new construction in the inner suburbs of the state’s big metropolitan areas. I was growing up in one of those suburbs east of San Francisco at the time, and the sharp rise in home prices that these policies enabled — funneled through the commissions earned by my real-estate-agent mother — effectively paid for my college education. Then, the summer after I finished college in 1987, I spent a month in the county courthouse reporting for the local weekly on a developer’s attempt to get one such ordinance declared in violation of state law because it kept the town of Moraga from meeting housing targets set by the Association of Bay Area Governments.

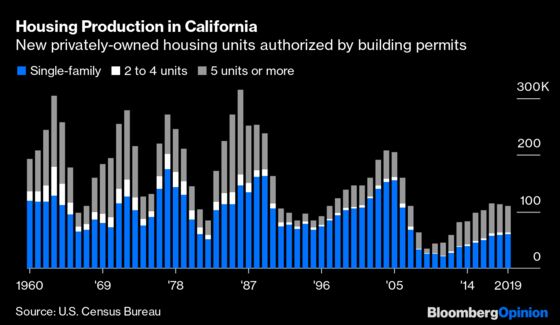

That attempt failed, and while there was still a lot of construction in the 1980s it was increasingly pushed to the farther reaches of the big metro areas. The last building boomlet, in the 2000s, consisted largely of single-family houses built in the Central Valley and the inland parts of Southern California, far from major jobs centers. Not coincidentally, these areas became epicenters of the housing bust that followed, and now top the national rankings for the percentage of “super-commuters” who travel more than 90 minutes to work (and 90 minutes back!) every day. In the Stockton metropolitan area east of San Francisco, 10% of commuters achieved that dubious distinction in 2016 and 2017, according to an Apartment List crunching of Census Bureau data.

In the anemic housing recovery that ensued starting in 2012, apartments (that is, units in multi-unit buildings) have constituted a slight majority of new construction, and those living near the major commercial districts of a few big cities and larger suburbs could be forgiven for thinking there was a major building boom afoot. But this pattern of “pockets of dense construction in a dormant suburban interior,” as economist Issi Romem described it, did not come close to meeting the housing needs of a state that — especially in and around San Francisco and San Jose — has continued generating lots of new jobs. It was also skewed toward large apartment buildings; construction of so-called middle housing in two-to-four unit buildings has, as is apparent in the above chart, more or less ceased.

Thanks to the efforts of Wiener and many others, the notion that this has to change has become increasingly accepted. The state that was to some extent the birthplace of the modern Nimby (for “not in my backyard”) movement has sparked a Yimby counterpart with growing political clout — clout that seems to be exercised along bipartisan lines, with Senate Republicans just as split in this week’s votes as the Democrats. Yimby ideas do seem to have much more currency in the Bay Area than in the Los Angeles area, which is home to the majority of those who voted “no” this week in the state Senate. And it’s not at all certain that SB 50, or something like it, would truly spur a construction boom big enough to make a real dent in the state’s housing shortages. But it’s telling that opponents don’t really have an alternate plan other than perhaps urging employers to locate jobs somewhere else.

To be sure, a lot of employers, and workers, are leaving. The annual net outflow of population from California to other states has gone up tenfold since 2010, estimates the Census Bureau. Although immigrants from abroad used to more than make up for that, they no longer do: The state has been experiencing net out-migration overall since 2017. The state is still growing thanks to births, though, and has an enormous backlog of unmet housing demand — a backlog that maybe, just maybe, it is about to start chipping away at.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.