Britain’s Housing Market Is Getting a Powerful Second Wind

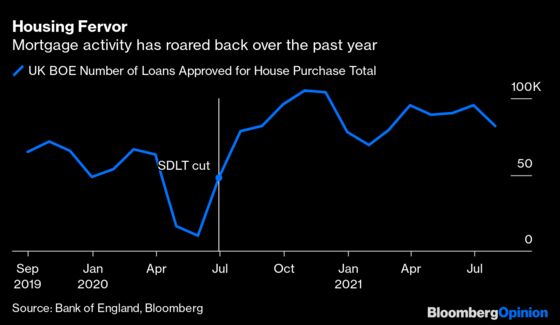

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.K. housing market is not alone in looking amped on steroids — we’re in a global asset price boom. But many expected things to stall when the break on property purchase tax (known as stamp duty), introduced by Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak to boost the pandemic-stricken economy, largely came to an end in June.

Instead, increased competition among mortgage lenders has given Britain’s market a powerful second wind by reducing borrowing costs to record low levels.

A number of lenders are now offering five-year fixed-rate deals at below 1%, a level unheard of in the U.K. It would appear that mortgage rates are only likely to go one way from here: down.

According to the Nationwide Building Society, after a slight drop in July, the cost of an average home roared back last month, rising 2.1%, which is only the second time there’s been a monthly gain of more than 2% since 2004.

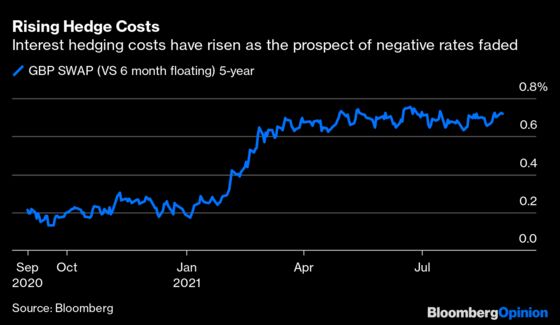

At first blush, this increased competition in mortgages would seem counterintuitive, especially with money market rates and gilt yields both heading higher. In recent months the threat of the Bank of England taking interest rates negative has receded, and those seeking to hedge their interest-rate risk have become more focused on borrowing costs rising. This has created something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, pushing up shorter dated swap rates in particular, which would normally also affect mortgage costs as lenders usually hedge their interest rate exposure in the money market.

As ever though, the housing market is more complicated. You need to dig a little deeper to understand what’s really going on.

One of the most significant factors is a shift in bank activity. When the stamp duty frenzy was in full flow, banks didn’t have to compete too hard for business. As the tax holiday drew to an end, however, it became clear that banks had more cash to play with than they had been expecting. This was because their customers were spending their pent-up savings more slowly than anticipated, and the banks themselves had not suffered the credit losses over lockdown they had provisioned for. The U.K. savings ratio has ballooned throughout Covid and is still at around 20%, up from a low of 5% in 2017.

As a consequence, banks are eager to lend and have pots of money available for the purpose. This high level of liquidity insulated them from developments elsewhere in the financial markets.

This isn’t the first time that mortgage rates have moved in the opposite direction to what one might have expected. In March last year the BOE cut its base rate in two steps from 0.75% to just 0.10%, yet average mortgage rates actually rose as lenders rushed to pull their most attractive and aggressive deals. The sudden drop in economic activity saw regulatory buffers kick in, as models pointed to large credit losses. Banks hastily withdrew products available to borrowers with high loan-to-income ratios — effectively shutting access to the property market for the least advantaged in society — and these are only gradually coming back.

The story is different today, in part because the stamp duty holiday helped to steer the property market through a very difficult time. Banks are now increasingly moving back to lending to customers they were rejecting less than a year ago. Mortgage rates are tumbling as a result.

Before the pandemic, the most competitive area of the market was for two-year, fixed-rate mortgages, which promised banks chunky fees, often amounting to 1,000 to 2,000 pounds ($1,379 to $2,757) every time a borrower sought to refinance. Today the fees are similar, but competition has driven five-year fixed rates to within 10 to 15 basis points of two-year rates.

This compressing spread between two-and five-year deals is encouraging borrowers to fix their mortgages for longer. Banks think they’re winning too as they see less risk and more reward with the extra maturity. It’s a rare win-win — and quite a different story than during the height of the 2007-2008 financial crisis when banks backed away from lending and drove mortgage costs up. Grab it while it lasts.

Increased competition is also having an impact on more niche areas. Mortgage brokers report strong interest in the refinancing of large mortgages (greater than 1 million pounds) to high-net-worth individuals and rising willingness from lenders to meet that demand. Flexibility is back.

Lenders are also exhibiting a greater appetite to offer high loan-to-value (LTV) mortgages. The best five-year fixed rate for a 90% mortgage is 2.69%, according to money.co.uk, which is significantly less attractive than the 0.98% rate available for those able to put up a much larger deposit and borrow only 60% of the home purchase price. But as the economy recovers, the next reduction in borrowing costs is likely to come from the higher LTV segment of the market — think of it as the leveling up that the government is so keen to see, though this is coming from commercial interests not regulation.

As for the property market itself, the availability of cheaper funding has come as buyers chase a shrinking pool of affordable family homes. According to Zoopla, supply constraints are most evident for properties priced up to 350,000 pounds. In other words, even if you can get the mortgage, good luck finding a home to buy.

Given these dynamics — a lack of affordable family-sized houses, combined with falling borrowing costs — the U.K. property market will keep motoring on. It’s a small, crowded island with ridiculous planning laws, after all. Those looking for high LTV mortgages might be rewarded by waiting for rates to fall further before committing themselves to a fixed-rate deal. But waiting too long probably means paying an even higher price — the classic dilemma in trying to get on the property ladder.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stuart Trow is a credit strategist at the European Bank for Reconstruction & Development. He is also a pensions blogger, radio show host and member of numerous retirement, finance and audit committees.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.