(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since the Coronavirus outbreak began, the U.K. has seemed more united than at any point in the last few years. The political logjam over Brexit has given way to solidarity against a common, invisible enemy. But beneath the surface, the divisions that defined the past four years persist and may grow as Britain’s transition period runs out.

Even amid the “rally round the flag,” there are still big differences between Remainers and Leavers, making questions over whether to extend the current Brexit transition period beyond this year particularly fraught. For example, while Boris Johnson’s satisfaction ratings were 72% in our recent Number Cruncher poll, this was 87% among Leavers and 57% among Remainers, and the same pattern was in evidence for other questions too.

This isn’t the extreme polarization seen in the U.S., but the Brexit effect is still there. Just because the public overall leans heavily one way, it doesn’t stop there being a 30-point gap between the two blocs, even if majorities of both approve of the prime minister’s performance. Within political circles the culture wars underlying the Brexit divide have played out too, particularly among coronavirus subplots, with battlegrounds including university bailouts, acceptable terminology and gender balance at the government’s press briefings.

The official government position is that the current transition period will end this year and that negotiations over future trade arrangements will be concluded or else Britain will trade with the European Union on World Trade Organization terms. The U.K. can request an extension of up to two years (something even the International Monetary Fund said recently would be a good idea), but it must do so by July. While the complexities of those negotiations — from fishing quotas to customs arrangements to questions of governance — receive limited public attention on their own, the prospect of additional economic stress, which might be avoided through extension, is likely to draw divisions to the surface as we move closer to the deadline.

Despite his campaign pledges, Johnson probably has the political capital to extend if he wants to. He finds himself in a historically strong position in the polls, and he’s fundamentally trusted by Brexiters in his own party in a way that his predecessor Theresa May was not.

Public opinion, as always, has multiple moving parts. Leave voters are divided on an extension to the transition period. There have also been questions asked about the U.K.’s non-participation in EU procurement schemes for personal protective equipment, where shortages for medical staff remain a major problem.

Europe’s own struggles to find a joint response that doesn’t widen the economic divide — and stoke political tensions — between southern and northern countries may also influence the U.K. debate over extension and its future relationship with its neighbors.

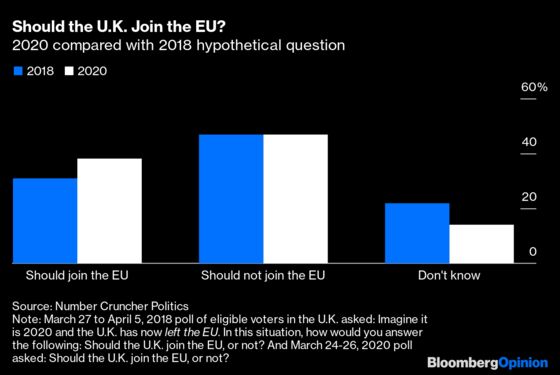

Back in 2018, we asked Britons to imagine it was 2020 and Brexit had taken place. How, in that situation, would they answer the question of the U.K. joining the EU? By a 16-point margin, the public said it should not. Two years on, we did a follow-up poll of 1,010 adults between March 24 and 26; the exact same percentage — 47% of eligible voters — told us the U.K. shouldn’t join. But 38% now think Britain should join, up from 31 points in our hypothetical 2018 question, while those unsure fell from 22% to 14%.

The shift is, predictably, among those who voted against Brexit in the 2016 referendum, with 73% of Remain voters now backing rejoining, up from 61% two years ago, while Leave voters were and still are solidly opposed (86%, statistically indistinguishable from the 84% recorded previously).

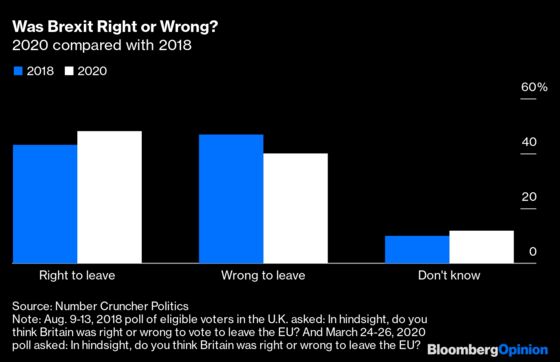

At the same time, more Britons are sure that leaving was the right thing to do. Asked whether Britain was right or wrong to leave the EU, “right” polled 48%, up five points compared with when we polled the Leave vote retrospectively in 2018, while “wrong” stood at 40%, down 7 points.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matt Singh runs Number Cruncher Politics, a nonpartisan polling and elections site that predicted the 2015 U.K. election polling failure.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.