(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Is your company immune to Brexit? With the looming threat of the U.K. leaving the EU without a withdrawal deal and a slim but rising risk of the pound plunging to parity with the dollar, more chief executives are telling investors they can handle any eventuality – however messy.

Unfortunately, having a fully fleshed out Brexit contingency plan is a luxury not all firms can afford. Nor does it solve the question of how any company will cope if a no-deal departure crashes the economy.

A hunt through Bloomberg’s trove of filings of company financial results throws up six publicly-traded companies that have labeled themselves “Brexit-proof,” or close to it. These are: healthcare facilities provider Primary Health Properties Plc; wealth manager Rathbone Brothers Plc; food producer Cranswick Plc; industrial real estate firm Stenprop Ltd.; Lloyd’s of London and the payments technology provider Net 1 UEPS Technologies Inc.

Their confidence stems either from the niche products that they sell, their domestic U.K. supply chains (meaning less exposure to a sudden rise in tariff barriers to trade), or the fact that they’ll keep EU-based hubs that remove the uncertainty of regulatory hurdles.

They’re not alone in their messages of comfort. Much of the finance world has had to prepare for the worst, including the likes of Barclays Plc, HSBC Holdings Plc and Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc. Other industries are joining the fray. “Leaving the EU without a deal is not corporate death for us, but it’s annoying,” the boss of the Volskwagen AG-owned luxury carmaker Bentley said this week. A no-deal scenario means only “mild disruption” for the retailer Next Plc, according to its CEO Simon Wolfson. Is this complacency or just sound planning?

There are three big Brexit risks cited frequently by companies: Tariff barriers, non-tariff or regulatory hurdles, and logistical issues such as holdups at ports.

On tariffs, the Confederation of British Industry lobby group has offered up some dire warnings, including textile imports from Turkey facing an average charge of 12% post-Brexit and vehicle exports to the EU getting whacked with a 10% levy. But some firms think they can take the pain. Next estimates 20 million pounds ($24 million) in additional input costs from import duties, equivalent to a 0.5% price increase on its clothing products. Chemicals producer Croda International Plc estimates a “mid-to-high single-digit million” impact from tariffs, a cost it would partly absorb and partly pass on to customers. Makers of higher end stuff, such as $200,000 Bentleys, will be confident of getting shoppers to fork out more if their costs go up.

On the threat of more regulation and other non-tariff changes, some CEOs are equally sanguine. Croda’s management says it’s ready to re-register its products in the EU in the event of a no-deal departure. Next says there’s no reason why independent testing of its products would stop them being acceptable to Brussels regulators.

On the fear about logistical snarl-ups in the immediate aftermath of a sudden U.K.-EU rupture, the more optimistic British bosses point to their stockpiling of goods and securing of alternative supply routes. Several say they’ve amassed six months’ worth of supply usually delivered from Europe. Bentley and Next say they can avoid the crowded Dover-Calais shipping route if it’s disrupted. “I’m much less frightened of no-deal,” says Wolfson.

It’s important to remember, however, that all of this preparation costs money (and that Wolfson is a Conservative Party peer and leave voter). A look at Next’s 11-page Brexit contingency plan published last year shows an elaborate new structure to limit the pain. It has set up a German company through which it intends to shift more European sales and an Irish entity to handle orders there.

Yet allocating millions to emergency plans means delaying investment or passing on the cost to suppliers or clients. Some companies can swallow this more easily than others. For Westley Group, a small foundry and engineering group, a loss of 2 million pounds in EU orders related to Brexit last year equated to 7% of its revenue. That’s significant.

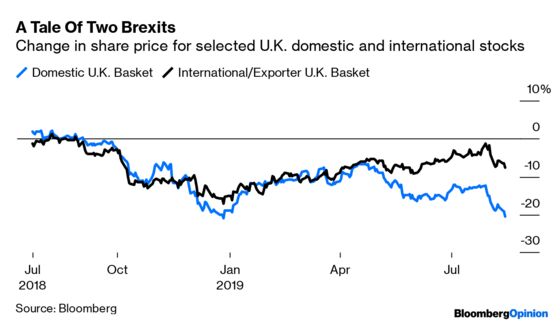

And managing to survive the worst ravages of a hard break with Europe won’t mean much if the U.K. economy is worse off. Investors are certainly betting that way by favoring the big, internationally diversified companies of the FTSE 100 over those that make most of their sales in Britain.

The chart above shows a 13% performance gap over the past year between the shares of British exporters (which get most of their revenue overseas) and those of domestically-focused U.K. companies. It’s interesting that the latter group include companies that claim to be fully prepared such as Barclays.

One thing CEOs can't control is investors’ own emergency plans.

--With assistance from Mark Gilbert .

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Brussels. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.