(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Five years ago, I emigrated to Germany from Russia, because it had abandoned any pretense of wanting to be a European country. Now, I’m watching in amazement as Britons — people we Russians have long considered the epitome of Europeanness — are doing the same, in droves, for the same reason.

It’s well known that tens of thousands of U.K. citizens have obtained second passports from Ireland as insurance against a post-Brexit loss of the European freedom of movement. But that’s only part of the story. Far more British citizens are applying for passports in other European countries than had been doing so before the Brexit referendum; they’re also moving to these countries in numbers not seen in a decade.

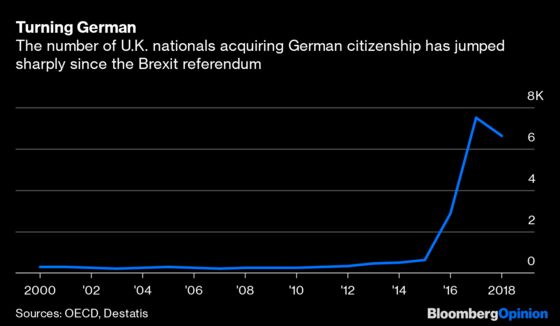

The number of Britons acquiring the German nationality, for example, has jumped from hundreds to thousands a year. There are so many of them they no longer get a traditional ceremony when they receive their German passports.

In 2014, five times as many Russians as Britons became naturalized Germans. The situation has reversed today: In 2018, 6,640 U.K. nationals obtained German passports, compared with 1,930 Russians. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s international migration database, after Brexit passed, the naturalizations of Britons also went up sharply in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Sweden, although the absolute numbers are smaller there than in Germany.

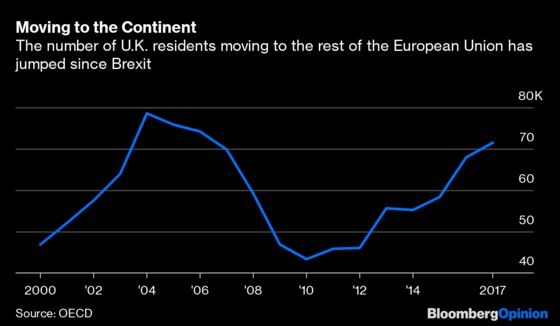

While Britons getting second passports from Ireland mostly aren’t going anywhere, there’s a substantial jump in U.K. emigration to the rest of the European Union.

While Britons migrated to the continent in similar numbers in the mid-2000s, about half of those emigres were moving to Spain, which marketed itself aggressively to retirees (and enjoyed a housing boom as a consequence). Today, the geography of the U.K. emigration is much more diverse. And, as with naturalizations, continental Europe is receiving significantly more U.K. nationals than Russians.

Data from the OECD are only available through 2017. But Daniel Auer of the Berlin Social Science Center, who is working on a study of recent U.K. emigration with co-author Daniel Tetlow, projects that the number of U.K. citizens moving to other EU countries increased to more than 75,500 in 2018, and will go up to almost 84,000 this year. That would be an absolute record.

The numbers are bigger than those reported by the U.K. Office of National Statistics for the outward migration of U.K. citizens --according to the ONS, net out-migration in the 12 months ending in March 2019 reached 52,000. But Auer considers OECD data and his extrapolations from national statistics in Germany, Spain and Ireland more accurate than British data, which is based in large part on passenger surveys.

It’s true that Britons face a lot less bureaucracy than Russians when they want to move to EU member states. And, unlike Russians, they are allowed dual citizenship in Germany while the U.K. is still an EU member. But I still can’t help my incredulity as I look at the numbers.

Russia is a corrupt country run by an authoritarian ruler who invades neighboring states, and it’s much poorer than the U.K. It fits the profile of a country of emigration much better than Britain does. According to Gallup data from the end of last year, 34 million people worldwide would want to move to the U.K. and only 8 million to Russia. And yet the U.K. appears to be beating my country of birth at driving people away.

The fact that the U.K. is still an attractive destination for immigrants makes it likely that post-Brexit Britain will be able to attract enough talent to replace those who leave. The foreigners still come: According to the OECD, the number coming to study — mostly from non-EU countries — has increased even as fewer people have been arriving to take jobs. But the U.K. government needs to pay more attention to how many citizens are leaving the country and declaring their allegiance to other European states. It needs more accurate statistics, obtainable from destination countries, and policies designed to persuade its people to stay or to come back if they’ve left.

The growing emigration of U.K. nationals is a measure of policy failure — just as it has been for the Vladimir Putin regime in Russia since the 2014 Crimea annexation. The U.K., like Russia, is losing people who disagree with insular policies. Brexiters may consider that good riddance — just like the Kremlin does. But I’m deeply convinced that countries need such people. They’re the the ones who connect nations in this increasingly small world, and with fewer of them, countries can quickly lose their edge.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.