(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Soho House looks like a members club, swims like a members club and quacks like a members club:

“From the beginning, and throughout our 25-year history, our members have always been at the heart of everything we do.”

But Soho House isn’t really a members club at all.

A genuine members club is owned and operated by its members, who take every decision from the makeup of the membership to the markup on the wine . In stark contrast, the 127,800 members of Soho House (and its satellite entities) are at the mercy of Membership Collective Group Inc. — “a global membership platform of physical and digital spaces” — which in June floated on the New York Stock Exchange.

Soho House is not alone: Any number of private hospitality enterprises masquerade as members clubs. The Membership Collective Group has taken the legerdemain to new lows with an IPO deploying a dual-class share structure that gives the company’s three main owners a veto over key decisions and board appointments.

A publicly traded private club is not just oxymoronic, it’s a tough business bet: Can you elongate the elastic of exclusivity without it snapping back in your face?

From its boho Britpop beginnings in London’s West End catering to “world class writers, artists, performers, directors, founders, designers and producers,” Soho House has rapidly expanded its global reach — opening 12 new houses since 2018, planning an additional 16 by 2024 (taking the total to 46) and predicting long-term growth of five to seven new houses a year. Simultaneously the club has extended its brand grasp with various membership-lite gambits (Soho Friends, Cities Without Houses) and commercial extensions, including Soho Home (buy the club’s design), Cowshed (spa products) and Soho Works (a WeWork me-too).

So far, even in a pandemic, so good: the Soho House waitlist currently stands at an all-time high of 63,700.

But the risk is that Soho House becomes a pyramid scheme of cool which must endlessly entice new members (to satisfy shareholder demands), without diluting its founding myth (and killing the golden goose). Can Soho House — which has never posted a profit in 25 years — unsphinx the riddle of exclusive expansion?

Not all are convinced. In 2019, for instance, the designer Archer Adams, an early member, published an excoriating resignation letter to the club’s founder Nick Jones :

“Soho House is simply not the same place it was when I first started going with friends circa 1997. I fear the club has become a somewhat premium version of WeWork.

… Now Soho House sends us reminders that we can purchase the same furniture and bedding featured in the houses for our own homes. Hustle, hustle!

… Food & beverage pricing which used to be reasonable since members subsidise your business with monthly dues has now been raised to the point that it’s on par with dining at many high-end non-members clubs.

… At the end of the day, Nick, I’m sure you’ll continue to make a lot of money, but the magic of original Soho House is now long gone.”

“Magic” is an odd description for a commercial transaction, but Soho House promises more than mere commerce. Whether it can fulfill this promise to the satisfaction of members and the market can now be tracked in real-time via the MCG ticker:

* * *

In many ways, Soho House is the poster-child of “brandlonging” — the strategy of ensorcelling consumers with bonds of belonging that blur the lines of trade.

Brandlonging isn’t new. For well over a century companies have sought to entwine loyalty and identity with a host of gimmicks — from copper tokens, box tops and bottle caps to trading stamps, cigarette cards and fan clubs.

But as branding becomes ever-more immersive, and technology ever-more pervasive, so brandlonging has become ever-more sophisticated.

Loyalty

Perhaps the simplest tool of brandlonging is the loyalty card, of which the humblest is a hand-stamped, wallet-sized, dog-eared piece of card. No names and no tracking drill, these buy-10-espressos-get-the-11th-free cards both formalize and scale the ad hoc relationships that local vendors have enjoyed with their clients since the dawn of trade. (Facial recognition existed centuries before CCTV.)

Like the tango, loyalty takes not just two, but time — a commercial dance elegantly explored by the New York Times restaurant critic, Frank Bruni:

“What you have with a restaurant that you visit once or twice is a transaction. What you have with a restaurant that you visit over and over is a relationship. … In return, regulars at most restaurants get extra consideration: a glass of sparkling wine that wasn’t asked for, a dessert that just appears, a promotion to the head of the waiting list when the place is full.”

It’s because “local loyalty” is personal and gradual that big brands have sought to replace cardboard and kinship with their hi-tech counterparts — first, magnetic-stripped plastic and now Near-Field Communication — which accelerate and gamify the bonds of belonging. These technologies are then tied to brand-specific loyalty programs or points-based eco-systems where spending on, say, a hotel room can be parlayed into cheaper car-hire.

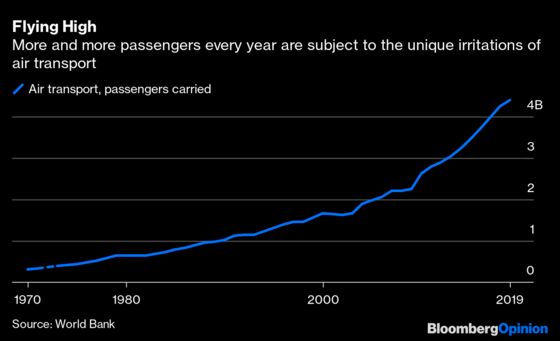

Few industries have weaponized loyalty as ruthlessly as airlines, for whom frequent flyer programs (FFP) are a vital tool of customer acquisition and retention (as well as an endless source of frustration and annoyance). The introduction of FFPs in the early 1980s soon collided with the acceleration of mass air-travel. As a result, what began as straightforward rewards programs quickly metastasized into Byzantine grail quests of points, tiers and statuses that were deliberately complexified by blackouts, expirations and fees.

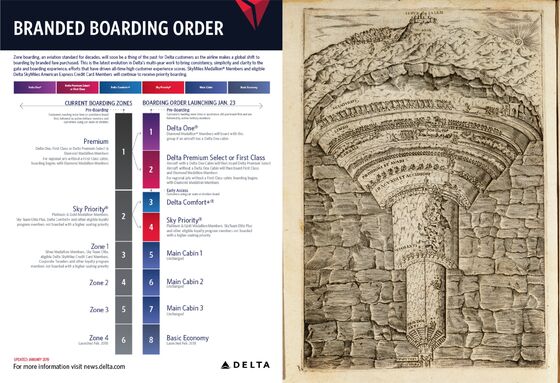

It can’t be coincidence that so many FFP “perks” are designed to cure irritations created by the airlines: baggage allowances, seat selection, check-in, lounge access, overhead bins. For instance, when in 2019 Delta decided to address the seething chaos of “zone boarding,” it did not select a more scientific system of enplaning, but instead unleashed “branded boarding” — an attempt to hammer home hierarchies of brandlonging as subtle as Dante’s inferno.

Such calculated immiseration has ignoble precedents: As the economist Jules Dupuit noted in 1849, early railway operators made first- and second-class travel more desirable by ensuring third-class carriages had no roof.

“Its goal is to stop the traveler who can pay for the second-class trip from going third class. It hurts the poor not because it wants them to personally suffer, but to scare the rich.”

Subscriptions

The problem with loyalty is that people are fickle. As a result, brands are anxious to up the ante of consumer commitment from “playing the field” to “going steady” with binding contracts, recurring payments and downloads of personal data.

A timely example of this transition was recently provided by the British sandwich slinger Pret a Manger, which last year replaced its loyalty cards with “YourPret Barista” — a subscription that, for £20 a month, offers customers “up to 5 organic coffees, teas, frappes, hot chocolates and more everyday.”

Given that a Pret cappuccino currently costs around £3, this seems like a genuine (and likely unsustainable) bargain — even if there’s a mandatory 30-minute ordering gap to prevent freebie coffee runs.

But Pret’s loyalty upgrade is not a patch on the Coffee-Industrial Capsule Complex being driven by Nescafe, Illy, Tassimo, Keurig and Lavazza. Having sold us their proprietary coffee machines, these companies now urge us to subscribe to their proprietary pods — a global supply-chain so absurdly elaborate that the inventor of the Keurig K-Cup, John Sylvan, told CBC: “I don’t know why people have them in their house.”

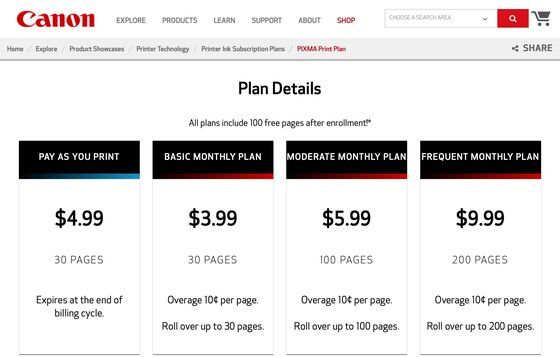

Curiously, the printer industry is attempting a similar approach to consumer thirst — with subscription plans that automatically dispatch ink in return for a monthly fee tied to a maximum number of prints. For example, Canon’s “Pixma Print Frequent Monthly Plan” charges $9.99 for 200 pages, and levies a 10-cent “overage” fee for every additional page.

Even if one ignores the questions of cost and sustainability, this transition from possessing objects outright to subscribing to their function must inevitably affect the emotion of exchange.

What does it mean to Rent the Runway rather than wardrobe clothes? Or to Spotify music rather than shelve albums? Or to stream the Criterion Collection rather than alphabetize DVDs? And how does this dovetail with the “right to repair” movement, which seeks to claw back the fundamentals of physical ownership in the face of “planned obsolescence”:

If ownership is personal and finite, and belonging is social and fluid, we may need to rethink the fundamentals of consumption. Remember the outrage when Amazon “memory-holed” George Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” from Kindles? Or when Apple inserted the U2 album “Songs of Innocence” into half a billion iTunes accounts? Imagine then the complexity, cost and consternation when every appliance and gadget is tied to a subscription and tethered to its maker via the Internet of Things. You may be confident that a water filter is good for gallon or two, but what if your “smart fridge” says no?

Membership

A supra-species of subscription also gaining traction is “membership” which offers “exclusive” benefits to anyone who can afford the fee. Traditionally associated with big-box warehouses (Costco, Sam’s Club, BJ’s), membership programs have permeated mainstream retail — from niche brands like Restoration Hardware, which gives 25% off full-priced items for an annual $150 fee, to behemoths like Amazon Prime, which now boasts more than 200 million members across 22 countries.

Membership’s promise is somehow to be chicer and more congenial than the sleeve tug of subscription, or the Sisyphean task of tallying points. Such claims to congeniality explain why so many brands are keen to camouflage their recurring fees (and data grabs) with nebulous talk of community:

WeWork • “Surrounded by a fast-paced and friendly community of professionals—and a cultural scene to boot—inspiration comes easily in our London locations.”

Fitbit • “The Fitbit Community is a peer-to-peer community for Fitbit users who are passionate about health and fitness.”

Blue Apron • “We introduce our community of home cooks to new ingredients, flavors, and techniques with seasonally inspired recipes that are delicious, fun, and easy to prepare.”

Soul Cycle • “In that dark room, our riders share a Soul experience. We laugh, we cry, we grow — and we do it together, as a community.”

That said, some brands just go for broke. Arsenal Football Club’s new and exclusive My Arsenal Rewards card now quadruples as a membership card, a rewards card, a matchday e-ticket and a payment card accepted anywhere that takes Visa — all designed to “help our members get closer to the club they love.”

Exclusivity

Others do so pretentiously — like Patek Phillipe which, since 1996, has run Riefenstahlian adverts claiming: “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely take care of it for the next generation.”

Actual exclusivity is a tough claim to stake, since brands premised on privilege are expected to deliver — something Simon Sinek noted while dissecting the fading glory of American Express back in 2009:

“To carry that green card with the Roman centurion in your wallet was a sign of success, a sign of independence, proof that you were going somewhere. But the brand built on the premise of “Membership has its privileges” seems to have forgotten its cause and become just another company selling credit-card services. In an attempt to capture all the market segments, to have something for everyone, AmEx has tarnished its brand.”

Although exclusivity is often delineated by price, it can be earned by dint of the physical limitations of space (museums, theatres, opera houses) and time (artists, tailors, joiners). The hottest restaurants become hotter still precisely because they have a finite number of covers. This creates a feedback loop of brandlonging where the excluded press their faces to the window, while the cognoscenti dial a network of secret numbers — as Helen Rosner observed in the New Yorker, “landing an impossible reservation can prompt a weird, almost embarrassing feeling of triumph”:

“The friends-and-family line for Pastis and Balthazar is an open secret. You’ll need to text the right person to get in at Emilio’s Ballato. The referral-only number for Bohemian, the secretive Japanese steakhouse, is a matter of extraordinary discretion, much like the restaurant itself.”

While some brands revel in this space/time conundrum, others seek to exploit it via cloning. For instance, The Ivy — one of London’s most exclusive restaurants — has opened some 36 Ivy Grills, Brasseries and Cafés across Britain since 2014 (with more clones to come), to allow hoi polloi a chance to sample its famous shepherd’s pie.

If this “exclusive lite” hospitality playbook seems familiar, note that The Ivy’s chairman, Richard Caring, is also on the board of Soho House’s Membership Collective Group.

Anti Social Social Club

Brandlonging rests on a delicate fulcrum: the extent to which consumers are prepared to sign up to regular payments (and sign away their data) in return for convenience, discounts, exclusivity and the lure of belonging.

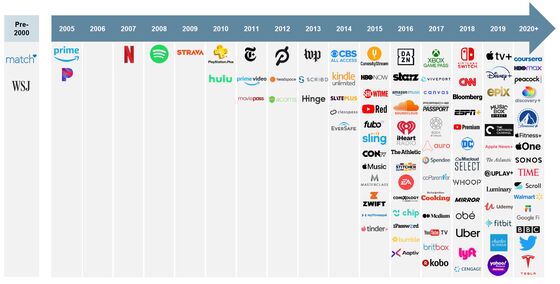

Even before Covid there was an ever-expanding range of physical products to which affluent consumers could subscribe, to say nothing of the exploding “digital subscription economy” partially charted below by Lazard:

And, study after study indicates that Covid’s lockdowns have only added accelerant. To give but one example, according to the Motion Picture Association global subscriptions to online video streaming services hit 1.1 billion in 2020 — a 26% rise on 2019.

For those who can afford it, the brandlonging economy promises nothing less than Life-as-a-Service — an appable, tappable, all-you-can-eat buffet of loyalty programs, subscriptions and memberships.

In this model, every consumer is a Sun King — orbited by a galaxy of subscription solutions, each fulfilling a singular daily need: coffee (Nespresso $50/month), exercise (Peloton $39/month), radio (SiriusXM, $10.99/month), shaving (Billie, $9/month), soap (Sudzly, $32/month), toothpaste (RiseWell, $10/month), deodorant (Bodhi Basics, $10.50/6 weeks), toilet paper (Reel, $32.99/month), underwear (BootayBag, $10/month), clothes (Haverdash, $59/month), video conferencing (Zoom $11.99/month), home accounting (Quickbooks, $25/month), business software (Microsoft, $69.99/year), printing (HP, $4.99/month), doorbell (Ring, $3/month), lunch (GrubHub $9.99/month), meditation (Headspace, $3.50/month), tea (Sips by, $16/month), books (BlackLit, $54.99/month), meal kit (Hello Fresh, $62.93/week), sponges (Skura, $12/2 months), wine (Bounty Hunter, $149/month), movies (Criterion Channel, $10.99/month), chocolates (Mystery Chocolate Box, $61.95/3 months), bubble bath (Bath Bevy, $41.95/month).

Just as it’s hard to imagine Soho House endlessly elongating the elastic of exclusivity, it’s tricky to see how enough consumers can continue to stretch themselves so thin. A 2018 survey found that Americans underestimated the amount they regularly spent on subscriptions by 197%; and 2019 survey founder the equivalent British underestimation was 413%.

Indeed, by now, these figures are likely themselves to be lowballs. According to a 2021 Deloitte report, Americans who subscribe to video or music streaming pay on average for four video and two music services; and those who subscribe to video games, pay for three different services.

But even for consumers who can tolerate the financial toll of accreting monthly fees, there are the privacy implications of endless data grabs; the environmental angst of excessive packaging and delivery; the practical frustrations of Balkanized provision; and the sheer bloody annoyance of relentless nudging and nagging (“Our T&Cs have changed!”).

Brandlonging is a trend of economic prosperity and financial security — the polar opposite of a hardscrabble, hand-to-mouth existence. If and when the music stops, the mystique fades and people start scanning their credit-card bills with a less indulgent eye, its true winners and losers will at last be revealed.

In 1824, the members of London’s Stratford Club become so annoyed by the antics of a fellow member (Major General Thomas Charretie) that one afternoon they voted to dissolve the club entirely. The meeting then adjourned to a downstairs room, where a new club was formed —The Portland Club —and every member of Stratford was elected to its membership, save one.

I was alerted to this (now cached) letter by Aaron Gell’s splendid Soho House long-read: “All Tomorrow’s Parties: Inside Soho House’s Post-Pandemic Comeback Play”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ben Schott is Bloomberg Opinion's advertising and brands columnist. He created the Schott’s Original Miscellany and Schott’s Almanac series, and writes for newspapers and magazines around the world.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.