Boris Johnson Hasn’t Heard the Last of Rory Stewart

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Rory who? The surprise in the Thursday’s Conservative Party leadership election wasn’t that Boris Johnson won. It was that Rory Stewart scraped through to the next round of voting. He may not get much further, but his name is still worth remembering.

Few expected the relative unknown to last this long. He had nowhere near the support of Johnson, whose frontrunner status looks unassailable. But Stewart’s campaign of home truths and warnings about fairy tale solutions may come back to haunt the favorite. Whoever wins the final vote by party members will be confronted with the same compromises on Brexit that turned the party base against Theresa May. Stewart was explicit about this; his rival has been anything but.

Both the 54-year-old former mayor of London, and Stewart, the 46-year-old international development secretary, come from privileged backgrounds. Both products of Eton and Balliol College, Oxford, they are skilled orators and profess to be moderates with a passion for social justice. Yet their campaigns could not be more different in style and – at least when it comes to Brexit – substance.

Johnson draws in bold, sweeping lines – the architect who shows you the home you might have if building codes were non-existent and your budget unlimited. Tell me your dream, he coaxes, and I’ll give it to you. When things go wrong, he blames the builders, or the planning authorities. In his case, many Tories (and some outside the party) are willing to suspend disbelief, ignore parts of his past that for others would have been career-ending, and just believe. He can promise tax cuts, but also to spend on public services. He has a Madonna-like ability to reinvent himself yet stay the same.

Stewart is more the engineer, a details man, but one with real conviction about where the country should go and what is possible. He speaks of the “wisdom of humility” and rejects the “competition of fairy stories” from both the left and right. “I do not believe in promising what we cannot deliver,” he told his audience at his campaign launch. Stewart has ruled out leaving the EU without a deal. His speech wasn’t just bold; it was one of the most compelling addresses British politics has seen in a long time. But a man without a chance can afford to throw caution to the wind.

The leadership candidates with a real shot at becoming prime minister all face an inescapable question. Do you tell hard truths, admit compromise is unavoidable, or seek to seduce the base? It’s not dissimilar to the decision that faced the U.S. Republican Party when they went with Donald Trump. Johnson is no Trump, and the two country’s systems are very different, but his choice to throw his lot in with the hard Brexiters now defines him; if he wins, the base owns him. Stewart’s overtly moderate stance appears to have been pitched at anyone but the party’s core supporters.

A look at the membership explains why Johnson feels he doesn’t have that luxury. Now an estimated 160,000, 70% of card-carrying Conservatives are male and nearly all are white. Their average age is about 57, though more than 40% are 65 and above, according to research conducted by Queen Mary University of London Professor Tim Bale and colleagues as part of the ESRC Party Members Project.

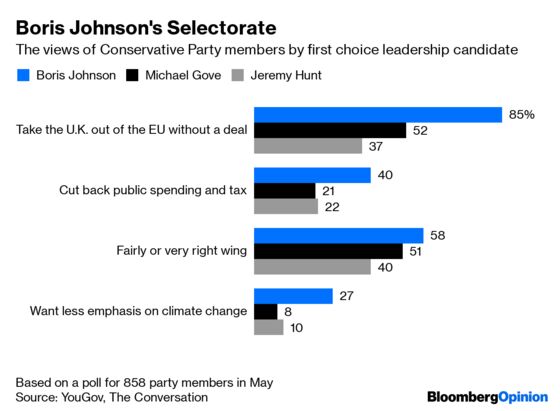

This group, though not monolithic, is unrepresentative of the wider country. Only about a quarter of the public support leaving the EU without a deal, but most Tory members want Brexit and they want it yesterday. No deal is fine with them. This is a community that is more likely to agree with Steve Bannon than Theresa May. A recent survey of party members’s views on three of the top candidates by YouGov shows just the extent of this tilt to the right.

That explains the bizarre spectacle of leadership candidates making pledges that range from the unrealistic idea of renegotiating the EU divorce agreement to the unconscionable, such as disbanding parliament temporarily to force a no-deal Brexit.

Johnson needs to escape that cage, and his emollient references to a “moderate, modern” conservatism show he’s aware of the need to broaden his party’s appeal. At his campaign launch on Wednesday, he was careful to say that a no-deal Brexit isn't what he wants, but what the country must be prepared for. His unique advantage as a candidate is his ability to reconcile the apparently irreconcilable. He will need it.

Even as he threatened a no-deal Brexit, a leaked cabinet note showed the country can't be properly prepared for the disruption of a no-deal exit by Oct. 31. And what Johnson doesn't say is that the real costs of leaving without a deal – the trade frictions, the non-tariff barriers, the reputational damage, the uncertainty of future negotiations – are longer term and impossible to negate through any kind of advance planning.

Whether Johnson’s positions will survive contact with Brussels is far from certain. As prime minister, he would face a choice of bitterly disappointing his base in the party, or plunging the country into the chaos of a no-deal Brexit or a general election. If that happens, Stewart’s warnings will look all the more prescient. Expect to hear him remind his party of this in any future leadership election.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael writes editorials on European politics and economics for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.