(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Bond yields are rising again, and everybody seems to be worried — again — that markets are on the precipice of a financial apocalypse — everyone except bond traders, that is.

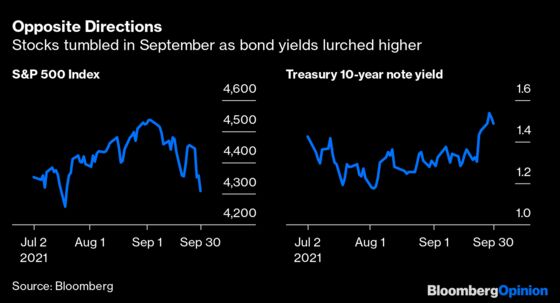

Stocks took a nasty hit in September, with the S&P 500 Index tumbling 4.76% in its worst month since the early days of the pandemic in March 2020. Much of blame was put on the bond market. Yes, yields did jump, with those on benchmark 10-year Treasury notes jumping 0.18 percentage point in their biggest increase since this March. And, yes, the Federal Reserve did just signal that it was ready to start pulling back the punch bowl. And, yes, the Fed is not the only one turning less dovish, with central banks now on their most aggressive interest-rate hiking cycle in a decade as measured by the strategists at Deutsche Bank AG.

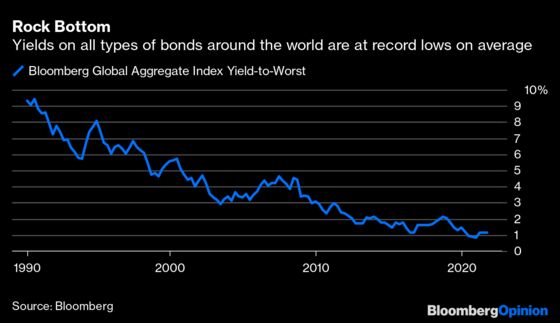

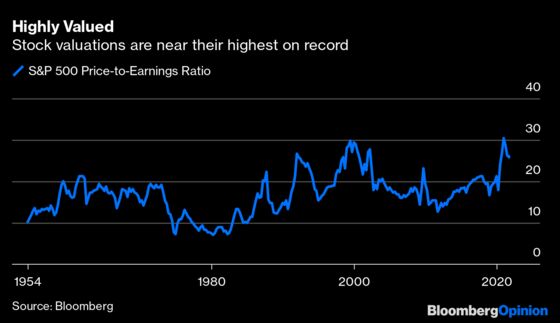

It’s generally accepted that the global financial system has become too dependent on the extraordinarily loose monetary policies of central banks. Record-low borrowing costs have led to historically high valuations in the equity market as well as record gains in housing prices and a borrowing spree by governments and companies. They can also be tied to the speculative frenzy in assets such as cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens.

So it’s not hard to see why markets might become nervous about the notion that money may be getting more expensive to obtain. The reassuring part is that those most closely associated with setting the cost of money — bond traders — don’t seem too concerned that we’re on the cusp of some secular reversal in interest rates that causes widespread pain throughout the financial markets. To see how becalmed bond traders are, just take a look at the ICE BofA MOVE Index. The measure of anticipated implied volatility ended the final week of September at 61.07, which is far below this year’s peak of 75.66 in late February as well as the historical average of 92.87, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

It’s understandable why equity investors specifically would be so concerned about rising bond yields. Alongside the trillions of dollars injected into the economy and financial system by the government and Fed, ultra-low rates are a chief reason stock valuations are near record highs as measured by various price-to-earnings ratios. The reason is that simple discounted cash-flow analysis shows that ever lower rates make future earnings more valuable in the present, justifying higher multiples for stocks even without profit growth.

A logical question to ask is how high bond yields would have to rise before equities start to look unattractive. One possible answer comes from the strategists at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., who wrote in a research note this week that 10-year Treasury yields would need to rise above 2.30% for relative equity valuations to rank above the long-term average. When might that happen? Not until the end of 2023, according to Bloomberg News’s monthly survey of more than 50 economists and strategists.

Another logical question to ask is why bond investors are so sanguine about the outlook. Perhaps they know how dependent the economy and financial system have become on low rates. Spurred by government borrowing, the amount of global debt outstanding has surged to a record $296 trillion, or 353% of worldwide gross domestic product, from about $210 trillion, or 320%, in 2015. Any significant rise in rates would make servicing that much debt almost impossible, leading to a true crisis. Central bankers, and by extension bond traders, surely know this, making it more likely that they would act to prevent a rapid rise in borrowing costs.

But let’s not forget that September is traditionally horrible for equities; it’s the only month to post negative returns on average not only since 1950 but over the past 10 years, 20 years and in post-election years, according to LPL Financial. This September seemed to be especially vulnerable, with the S&P 500 having risen for seven consecutive months, which is a rarity, as well as not suffering a 5% pullback in 2021 up to that point, which is something that LPL says happens on average three times a year. (That 5% threshold was reached between Sept. 2 and Sept. 30.)

The good news is that stocks have history on their side. After seven-month winning streaks, the S&P 500 has been higher six months later 13 out of 14 times since 1950, with an impressive 7.8% average return. Much of the angst in equity markets last month was similar to September and October of 2020, when the S&P 500 fell 6.69% as yields bottomed and began to rise. But that proved short-lived, with the S&P 500 actually rising 20.2% between Aug. 4 — the day 10-year Treasury yields bottomed at 0.51% on a closing basis — and March 31, when they topped out at 1.74%.

Sure, a lot has changed between then and now. For one, the Fed back then wasn’t even hinting at starting to taper its $120 billion of monthly bond purchases. But perhaps more important for equity investors, the economy finally looks as if it no longer requires extraordinary support. So what are we to make of the September sell-off if it’s not a “taper tantrum?” How about calling it a refresher.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is the Executive Editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global Executive Editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.