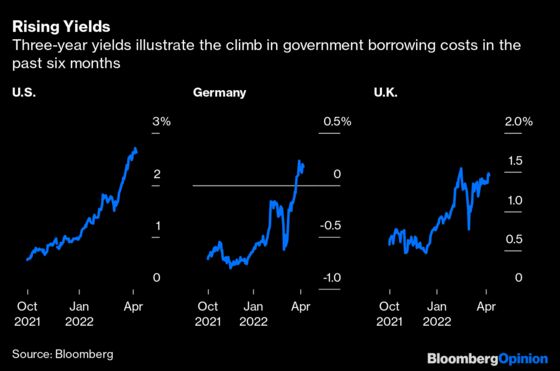

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The bond-market beatings will continue until morale improves. It's not been much fun investing in fixed income in recent months. The three-year U.S. Treasury yield, for example, has risen fivefold since the start of October; the ascent shows little sign of abating. If bond traders are correct in their prognosis that inflation has raced to become endemic rather than transitory, the stock market better watch out.

Central bankers everywhere are feeling the pressure to emulate Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve chair who famously tackled inflation by cranking up interest rates in the early 1980s. “Reducing inflation is of paramount importance,” the usually dovish Fed Governor Lael Brainard said earlier this week. But as U.K. hedge fund manager Crispin Odey, who’s made big profits this year betting against bonds, put it in a letter to clients last month: “Everybody knows that the West is bankrupt somewhere around interest rates of 3%, so the fight now is how can 0.5% interest rates slow down inflation which is potentially on its way through 10%.”

The rapidity of the change in the inflation outlook was detailed in a speech earlier this week by Agustin Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements. Carstens suggested a “change in paradigm” may be needed, because capping the rise in consumer prices is inconsistent with the growth-fostering monetary and fiscal policies central banks and governments have pursued in recent years:

We may be on the cusp of a new inflationary era. The forces behind high inflation could persist for some time. New pressures are emerging, not least from labor markets, as workers look to make up for inflation-induced reductions in real income. And the structural factors that have kept inflation low in recent decades may wane as globalization retreats.

Former Fed policy maker Bill Dudley warned recently in a Bloomberg Opinion column that for the central bank to be “effective” in calming inflation, “it’ll have to inflict more losses on stock and bond investors than it has so far.” An environment where interest rates rise rapidly could trigger an ugly mess in equities, which can be hard to stop. Add in the fact that economists surveyed by Bloomberg put the chances of a U.S. recession in the coming 12 months at 20%, and the stock market looks increasingly vulnerable to a selloff.

Too much money sloshing around the system for too long has undoubtedly contributed to the inflationary mess, driven by a Fed balance sheet that’s ballooned to $9 trillion. The central bank, which only stopped adding to its bond pile last month, now wants to reverse direction sharply. On Wednesday, it signaled in the minutes of its most recent meeting that it’s contemplating both bond sales worth $95 billion a month and half-point jumps in interest rates. And at the European Central Bank policy gathering last month, “a large number of members held the view that the current high level of inflation and its persistence called for immediate further steps towards monetary policy normalization," minutes published on Thursday showed.

Weaning financial markets off monetary stimulus will be tricky. Who will buy the bonds the Fed no longer wants? Much as the alleged benefits of quantitative easing resist quantification, it’s impossible to calculate the repercussions of the exit plan in advance.

The S&P 500 index is only down 6% this year, which feels wrong if Corporate America decides it needs to hold off on spending and hunker down for a coming economic storm. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has stressed the need for a nimble approach to policy making. The fancy footwork required to pull off a soft economic landing and avoid recession while curbing inflation will require the agility of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. With central bankers unlikely to match the female half of the dancing duo’s prowess at performing the steps backward and in high heels, stumbles look likely.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- If Stocks Don’t Fall, the Fed Needs to Force Them: Bill Dudley

- An Inflation Update and How Brainard Gets it Right: John Authers

- All That’s Stopping a Full-Blown Food Crisis? Rice: Javier Blas

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.