Boeing’s 737 Max Crisis May Cost It the Upper Hand

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Boeing Co. CEO Dennis Muilenburg has called the crisis surrounding the company’s 737 Max jet a “defining moment” that will ultimately make the planemaker stronger and better. It also may turn out to be a defining moment for Boeing's suppliers, one that has the potential to shift the balance of power back in their favor.

The global grounding of the Max is nearing its third month as Boeing works to present regulators with a fix for the flight-control software system that was a key factor in two fatal crashes of the jet. With the exception of perhaps the airlines that use the Max and Boeing’s own executives, no one is rooting harder for the jet’s return than the suppliers whose revenue and profit goals are very much entwined with its continuing success.

Boeing’s relationship with its supply chain is complicated, though. Over the past few years, the aerospace giant has taken aim at its suppliers’ profit margins, squeezing parts-makers for cost cuts and steadily encroaching on their territory with its own offerings. Theoretically, it’s a partnership. But Boeing seemed to always have the upper hand. Boeing called its cost-cutting initiative “Partnering For Success”; parts-makers call it “Pilfering From Suppliers.” Now, however, Boeing is on the defensive, and it’s in large part because of a software system for which it bears responsibility.

Uncomfortable questions still remain unanswered: Did Boeing cut corners in its desire to speed the Max’s entry into service? Did its obsessive focus on cash flow create a culture where employees were incentivized to bury bad news and make the project work at any cost? Was the Federal Aviation Administration rigorous enough in its oversight of the aerospace behemoth? An accounting for whatever design miscalculations, regulatory lapses and cultural shortcomings allowed the Max to crash needs to happen. Safety is everyone’s top priority. But the Max crisis should also force a conversation about how much control Boeing already has over the aviation market, and whether it’s in anyone’s best interest for the company to continue to expand its power further by bringing more of its supply chain in-house. A humbling of Boeing and its ambitions could be a healthy outcome.

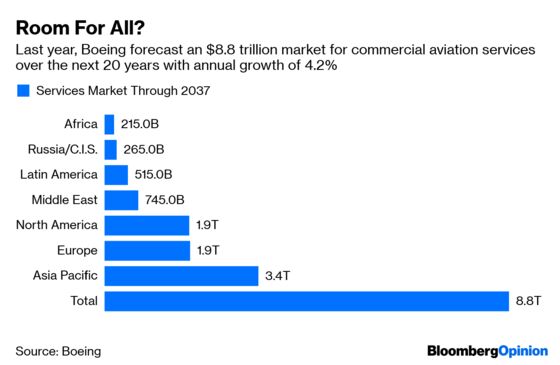

One reason Boeing’s nearly $200 billion market value has slipped only marginally since the first Max crash in October is that investors are taking some comfort in the benefits of the duopoly the company shares with Airbus SE. If airlines wanted to hold Boeing accountable for its poor communication and other missteps, canceling orders isn’t really an option unless they’re prepared to join the back of the line at Airbus and wait years for their jets. That’s hardly the kind of dynamic that’s going to force Boeing into a deep rethink of its ways. And the industry is consolidating further: Airbus acquired Bombardier Inc.’s C Series program (now called the A220) and Boeing is moving ahead with a commercial-aircraft joint venture with Embraer SA. Muilenburg, speaking at a Bernstein conference on Wednesday, said he also still aims to build a $50 billion business focused on after-market services.

Muilenburg said Boeing only invests in vertical integration and services when the company thinks it can add value for customers in terms of cost and capability. It doesn’t want to completely replace its supply chain, he said, and if Boeing is right in its prediction that growth in air traffic will spur demand for more than 42,000 new planes over the next 20 years, there’s plenty of work to go around. But the company’s forays into parts and services have spooked investors: Avionics-maker Rockwell Collins Inc. fell by the most in nearly six years the day Boeing announced it would launch its own business focused on navigation, flight controls and information systems. United Technologies Corp. eventually bought Rockwell for $30 billion because the companies believed they needed to get bigger to better survive Boeing’s onslaught.

Boeing set the requirements for the Max’s so-called Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, including allowing the software to aggressively push the plane's nose down based on a single sensor reading. The system was meant to guard against a possible aerodynamic stall after the decades-old 737 model was redesigned to accommodate larger, more fuel-efficient engines. While Boeing has resisted any claims of flaws in initial design of the software, 346 dead people and the fact that there’s a need for a fix before the planes can be returned to the sky would seem to suggest otherwise. Boeing previously had an internal avionics group that it largely shed in a push toward outsourcing following the 1997 merger with McDonnell Douglas Corp. In some ways, this experience reinforces a contention long made by suppliers such as Rockwell that they aren’t so easily replaced.

I have been skeptical of United Technologies’ takeover of Rockwell from the start. Past history would suggest the benefits of size are limited when it comes to dealing with Boeing. When United Technologies, fresh off its $18 billion purchase of Goodrich Corp. in 2012, balked at discounts Boeing demanded on landing gear for the 777X, the planemaker gave the contract to a small Canadian company instead. Boeing initially bad-mouthed the United Technologies-Rockwell deal, but eventually came around after getting the companies to sign onto its cost-cutting initiative. That made the deal feel even more like a highly expensive bet with dubious payoffs. I could easily see a meaningful part of the $500 million in cost savings United Technologies was targeting from the deal accruing to Boeing’s bottom line instead. Now, though, I’m not so sure.

It’s not inconceivable to me that suppliers, particularly those with scale like United Technologies, may be emboldened by the Max crisis to push back more on future aircraft designs to protect their market share and margins. You see some of this already in other corners of the aviation market: Ryanair Holdings Plc CEO Michael O'Leary told Bloomberg TV earlier this month that Boeing needs orders and Ryanair has cash – “if the pricing is right.” It’s also possible that Boeing instead tries to force even more cost cuts on its suppliers as it works to offset the financial hit of having the Max grounded. We may not know for years which way the pendulum swung, but the continuation of Boeing’s grip over the aerospace industry shouldn’t be seen as a foregone conclusion.

Boeing already builds the carbon-composite wings for the 777X wide-body model that’s set to enter service in 2020 and does work related to nacelles, or engine casings. Last year, it paid $4.25 billion to acquire KLX Inc.’s aerospace parts distribution operations. It’s also launched an aircraft interior joint venture with Adient Plc and an auxiliary power unit partnership with Safran SA.

Boeing set the requirements for the software, while Rockwell programmed the lines of code underpinning the system and built the physical box that it runs on, according to the Washington Post. United Technologies made the angle-of-attack sensors that trigger the MCAS system.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.