There’s More to the $1 Trillion Deficit Than Just Tax Cuts

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In the two years since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 took effect on Jan. 1, 2018, the annual U.S. federal deficit has grown from $681 billion to a bit over $1 trillion, according to numbers released last week by the Treasury Department.

Did the tax cuts cause the deficit increase? At first glance, no. Federal revenue in calendar year 2019 was $154 billion higher than in calendar year 2017, while spending rose $494 billion.

But such an accounting doesn’t really tell us much. It ignores inflation, which isn’t very high these days but still high enough to matter, and it fails to consider what probably would have happened had there been no changes in fiscal policy. In a growing economy, both tax revenue and spending tend to rise over time in real terms. In good times, tax revenue usually goes up faster than spending; during recessions, revenue falls and spending jumps.

The last recession followed the usual pattern, but took it to extremes, with revenue falling and spending rising by more than 15% year-over-year. In the early years of the current expansion, revenue growth and spending growth also followed a somewhat exaggerated version of the usual good-times pattern, only to trade places in 2016 as the 2015/2016 mini-recession cut into tax revenue.

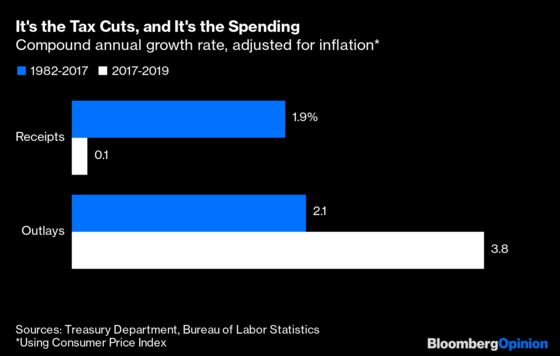

When revenue fell again amid a strengthening economy in 2018, the tax cut seemed to be the obvious cause. In 2019, revenue rebounded a bit and spending growth accelerated. Put the two calendar years since the tax cut together and compare them with the “normal” of the previous 35 years, and it’s clear that recent revenue growth and spending growth have both been out of the ordinary.

Real outlays grew 1.7 percentage points a year faster than the historical average since the end of 2017; real receipts grew 1.8 percentage points slower. Both thus seem about equally to blame for the rise in the deficit.

Or both deserve about equal credit, if you prefer. There has been a big course shift among macroeconomists in recent years over the risks and rewards of fiscal stimulus. The rise in the deficit since 2017 has so far been accompanied by solid if unspectacular economic growth and near-record-low unemployment rates. Maybe this unconventional late-expansion experiment in stimulus will come to be seen as a huge success.

Supporters of the tax bill also argued it would stimulate faster long-run growth by changing the incentives facing business, in particular by boosting investment. But while business investment rose in 2018, it fell in the second and third quarters of 2019. This may say more about the uncertainty brought on by President Donald Trump’s trade policies than the merits of the tax cuts, but in any case there’s not much evidence yet that the incentive effects of the tax cuts will contribute significantly to future growth.

There is ample evidence, on the other hand, that it has contributed to a rise in the federal deficit. But so have spending increases. Net interest on the debt accounted for the biggest part of the spending rise from fiscal year 2017 to FY 2019, according to the Congressional Budget Office, with Social Security, defense, Medicare and Medicaid also seeing big increases. With the exception of defense, none of these are discretionary categories that Congress can adjust as part of the annual appropriations process. Social insurance spending — what those who want to cut it call “entitlements” — will keep rising in the absence of major, controversial changes. The rise in net interest payments has thus far been kept somewhat in check by extremely low interest rates, which may or may not continue in the future.

The CBO will release new 10-year budget forecasts next week, and they’ll show a lot of red ink. They will also probably show deficits shrinking a little after 2025, when some of the 2017 tax cuts are set to expire. But the temporary tax cuts in the 2017 bill were generally those for individuals, so Congress will feel a lot of pressure not to let them lapse. The CBO forecast also probably won’t include a recession, and one of those would drive the deficit much higher.

As a onetime deficit worrier who has seen pretty much none of the big concerns of deficit worriers in the 1980s through early 2010s come to fruition, I’m not going to get all apocalyptic about this. But a combination of long-ago policy choices and recent ones have put us on a path where those who continue to worry about deficits are going to have a lot more to worry about.

This is how far back the monthly Treasury Department data goes that allows one to calculate by calendar year instead of just fiscal year, but it also more or less coincides with the modern economic era of less-frequent recessions and slower growth.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.