Big U.S. Banks Have Been Stars, But the Encores Are Over

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- America’s biggest banks have had star turns this year for investors betting on the global economic rebound from the Covid-19 pandemic, but the encores might well be done.

Lenders from the U.S. and Europe have comfortably beaten earnings expectations while the world grappled with economic shutdowns and reopenings. But with third-quarter earnings coming up — starting with JPMorgan Chase & Co. on Wednesday — there’s now a chance of some disappointment.

The key is going to be old-fashioned lending and whether it has started to pick up. A big part of the bull case for banks is that people and businesses will start to borrow more again after months of paying down loans and credit cards. With rising interest rates, the argument goes, this will finally bring an upturn in interest income and margins.

But both sides of this line look flawed. U.S. interest rates aren’t going up very much anytime soon and in three years could still be barely more than 1%, according to market indicators and analysts. Meanwhile, bank executives presenting at financial conferences in recent weeks gave cautious guidance on loan growth. Banking bulls may have gotten ahead of themselves.

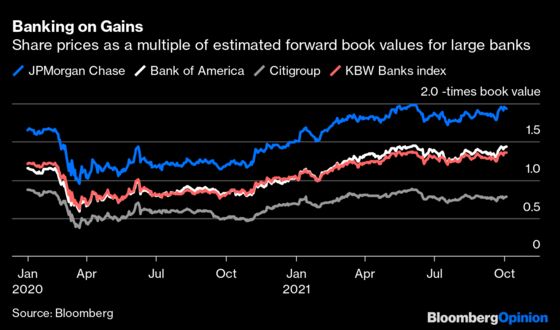

Big bank stocks have rallied dramatically this year — even Citigroup Inc., the worst performer among the largest lenders, has kept pace with the S&P 500. This has driven valuations to around the highest in three years when looking at prices as a multiple of forecast book values.

The blistering performance came from two surprising outcomes of the Covid crisis that have played havoc with analyst and investor attempts to predict bank earnings. Bad loans haven’t turned out to be anywhere near the problem that banks initially expected them to be, while capital-markets activity has boomed in a way not seen since 2009. Both resulted from the huge and rapid wave of government and central bank cash unleashed to support incomes and markets through multiple economic lockdowns.

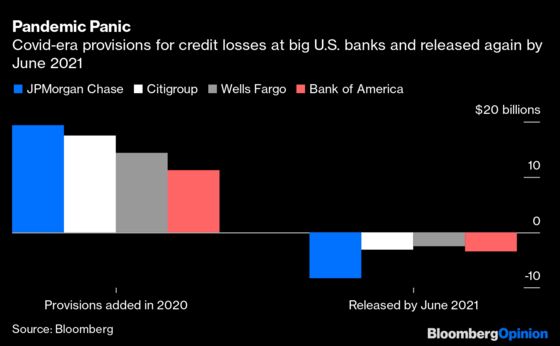

The good news on bad debts has been one big boost to results so far this year. Everyone expected painful losses from companies and people defaulting on their debts when the pandemic began and banks salted away billions of dollars in provisions to cover these. But the provisions haven’t been needed: JPMorgan has already released $8.3 billion of the $19.4 billion it put aside in the first six months of 2020, for example.

Next, the Federal Reserve’s backstopping of markets brought a boom in stock and bond trading, corporate fund raising and mergers and acquisitions. Last year, the biggest U.S. and European banks ended up with the greatest revenue from investment banking and trading since 2009’s record levels, according to Bloomberg data. That flowed over into the first quarter of this year, but most activity has now begun to slow down towards more normal levels.

The knock-out revenue continues in some areas: For example, fees from advising CEOs and private-equity titans on deal-making. But bond and currency trading, and new stock and bond issuance are declining significantly. This year’s investment banking and trading revenue is, however, still expected to beat the totals in much of the previous decade, according to analysts.

The investor response to all this was first to slash expectations for bank earnings then scramble to guess how high they could get. Forecasts for this year’s earnings among members of the KBW Bank Index more than doubled between January and now, according to Bloomberg data.

But the scrambling is done and analysts have trimmed back forecasts for some banks for this quarter. In 2022, the air will come out of the Pandemic boom. Earnings per share are forecast to be lower by an average of nearly 15% for the big six U.S. banks.

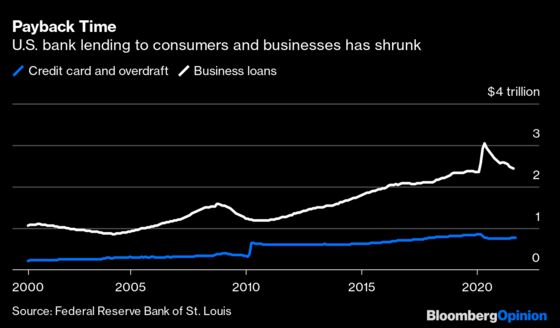

Even hitting those numbers relies on the expected recovery in the volume and profitability of lending. The flip side of all the government’s Covid support has been that banks’ loan books have shrunk.

U.S. credit-card and overdraft balances have stopped falling, but are still almost 11% below where they were in March 2020, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis. Consumer spending in a healthy reopening is expected to lead to growth soon, but retail deposits are still very high after a long spell of direct payments from the U.S. Treasury and subdued spending during lockdowns. People still have a lot of cash and any bumps in the road to recovery will mean savings last longer before fresh borrowing is needed.

Commercial and industrial loans spiked at the start of the pandemic when companies drew down their corporate overdrafts as a precaution against falling revenues, but these balances shrank rapidly as companies raised cheap, long-term finance in bond markets. Balances now are slightly higher than they were before the spike, but probably slightly lower than they would have been had pre-pandemic growth rates continued. And they are still declining.

These kinds of loans typically see double-digit percentage growth in the year after a recession, according to Betsy Graseck, analyst at Morgan Stanley. But this isn’t an ordinary recession and the flood of bond issuance by companies means many could have raised all the funding they need for a much longer period than normal, which would hold back a recovery in loan growth.

There’s also room for disappointment on how profitable new lending will be and that’s because interest rates don’t look to be rising as quickly or as much as seemed likely earlier this year. Futures markets predict that the Fed Funds Rate will be barely above 1% at the end of 2024, while banks analysts at Citigroup have just cut their forecast for U.S. rates for the same period to 1.1% from a previous forecast of 1.6%.

Investors typically bid up bank stocks when long-term interest rates are much higher than rates today. One key guide for this is the difference between yields on 10-year Treasuries and two-year Treasuries — in finance-lingo the steepness of the yield curve. The simplistic idea is that banks’ funding costs are close to short-term rates and their income from lending is closer to longer term rates: the steeper the curve, the more profitable banks will be.

Right now, the gap between 10-year and two-year Treasury yields is just 1.24 percentage points – the average over the past 20 years is 1.36 percentage points — after the curve flattened out a lot over recent months.

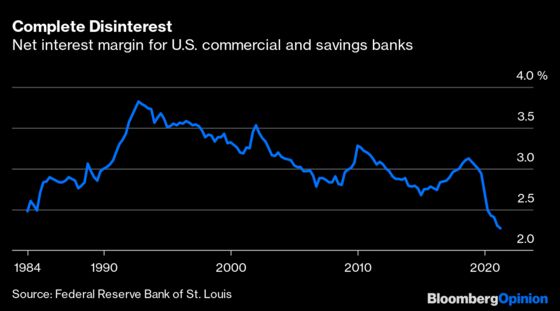

Combine this fact with banks’ shrunken loan books and lending is producing among the weakest returns ever. For all U.S. banks, net interest margin — total interest income as a proportion of loans and other interest earning assets — is at its lowest level since 1984, according to data from the St. Louis Fed. It has fallen steeply since autumn 2018.

It is hard to see what will improve lending profitability in future. Banks know this and that’s part of why many are moving into alternative businesses and looking for growth elsewhere. These efforts range from JPMorgan’s deal to buy food and restaurant review website the Infatuation, to Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s takeovers of European money manager NN Investment Partners and the U.S.'s “buy now, pay later” business GreenSky.

These offbeat plays won’t make much of a difference in the short run. So it might be time for investors to cool their newfound love for big banks.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.