Big Oil’s Windfall Creates a Quandary for the Industry

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I hope you’re sitting down for this news: Oil companies look set to make a lot of money. I know. But trust me, this year, it’s really a lot of money.

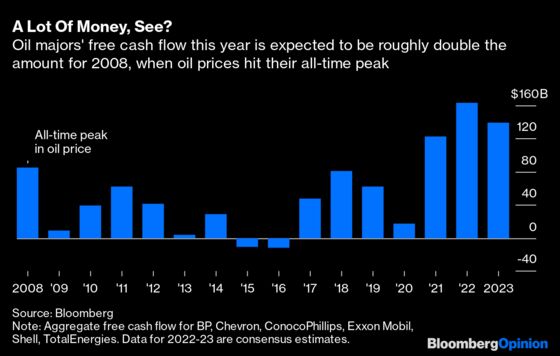

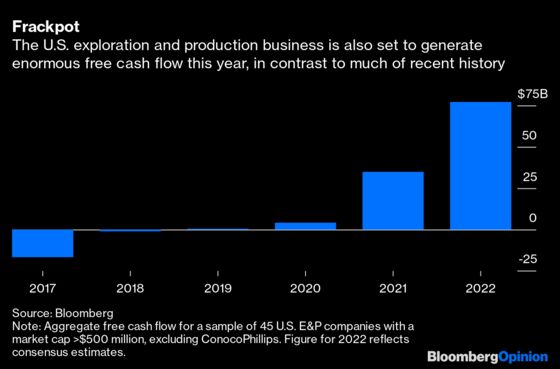

Six of the largest Western oil producers — BP Plc, Chevron Corp., ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil Corp., Shell Plc and TotalEnergies SE — are expected to generate free cash flow, after capital expenditure, of $163 billion this year. That is virtually double what they made in 2008, when oil prices hit their all-time peak of almost $150 a barrel, and they actually produced slightly more oil and gas. Their smaller competitors in the U.S. exploration and production business are also in for a big year.

This leaves the industry with an unfamiliar conundrum: What to do with all the cash? First-world problem, perhaps, but at this moment a potential problem nonetheless.

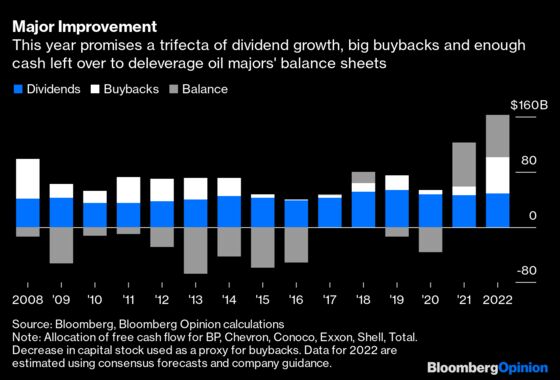

The past decade, which saw a boom in shale production but a bust in oil stocks, has refocused attention on the main thing that executives are supposed to do well: allocate capital. This year, there would seem to be few hard choices. For the big six, in round numbers, almost $50 billion would go to dividends. Assuming buyback targets get front-loaded, those might take another $50-55 billion, potentially bringing total shareholder payouts to more than $100 billion for the first time ever (2008 payouts were just shy of that level). Even then, roughly $50 billion of excess cash flow would be sitting on balance sheets, taking collective net debt down from 0.9 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization to less than 0.5 times on a pro forma basis.

For energy investors, this combination of a 7% payout yield plus continued deleveraging — the polar opposite of what they got for much of recent history — is about as good as it gets. With consensus estimates pointing to free cash flow of almost $140 billion in 2023, the industry could repeat the trick next year.

When oil companies are rolling in it, though, the first order of business in Washington is to accuse them of profiteering. Especially when there’s a (proxy) war on:

We are here today to get answers from the Big Oil companies about why they are ripping off the American people. At a time of record profits, Big Oil is refusing to increase production to provide the American people some much needed relief at the gas pump.

That was Rep. Frank Pallone of New Jersey opening a hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Committee earlier this month. Democrats are well aware of the dangers posed by surging gasoline prices, among broader inflation, ahead of the midterms. While Russian President Vladimir Putin is one target of blame — and justifiably so — the instinct to lambast oil companies for gouging drivers at the pump is never entirely dormant, even though the accusation is bogus.

It’s also important to emphasize a big difference between 2008 and now. Back then, the boom in oil prices was nearing a crash, and the majors were still earning high returns on capital (for more detail, see this excellent blog post by Arjun Murti, the former Goldman Sachs analyst who called oil’s “super spike” back then and is now on the board of ConocoPhillips). Today, we are just emerging from an oil crash of generational proportions and years of low returns. In addition, whereas peak oil supply was the big fear back in 2008, climate change now shifts the focus to predicting peak oil demand. Free cash flow is high not just because of rising oil and gas prices but because oil companies did the rational thing and suppressed their longstanding impulse to immediately spend most of every dollar that comes in.

Even so, the industry’s sudden liquidity appears to be making it nervous. Calls this year for President Joe Biden to effectively give permission to drill — bizarre when onshore federal lands account for only about a 10th of U.S. production — can be read as trying to deflect the ire of Main Street. The ritual shellacking on Capitol Hill was an attempt by Democrats to shift it back.

If oil prices spike further, things may get really tricky. Apparent Russian war crimes in Ukraine, along with expectations of a new offensive, suggest that European Union sanctions on Moscow’s energy exports have become a question of when rather than if, although the form and timing remain debatable. The disruption involved could well touch off a super-duper spike in energy prices — and upgrades to those cash flow forecasts.

Recent history suggests that high pump prices have a way of pushing Congress, including its Republican members, toward higher taxes on oil producers. In 2006, when Republicans controlled both chambers and had a former oilman in the White House, they nonetheless removed a tax break for several oil majors related to amortization of exploration expenses as gasoline nudged above $3 a gallon. Two years later, that same ex-oilman, albeit a lame duck by then, signed into law further changes for oil producers that effectively raised their taxes. Kevin Book of ClearView Energy Partners — to whom I am grateful for that oil taxation history lesson — points out that the 2008 tax changes feature again in the House-passed version of Biden’s stalled Build Back Better package.

Besides showing that high pump prices can soften Republicans’ traditional aversion to windfall taxes on oil producers, these examples also show that there are ways of extracting money without calling it a windfall tax. Biden’s call for fees on idle wells can be viewed this way. Clearly, for now, Republicans are focused on tying high pump prices to Biden’s green agenda, and Build Back Better is all but buried.

Yet if oil heads up toward $150 or higher, oil majors may want to look over their shoulders. Despite the premise of that ridiculous recent hearing, they don’t control oil prices. They do control spending and communication, however. It will be interesting, for example, to hear the messaging around dividends and buybacks on imminent quarterly earnings calls; one suspects it may have a sotto voce quality. Big budget increases to take advantage of higher oil prices — and join the “war effort” — are unlikely for now, given the reasons discussed above plus the growing risk that a recession might undercut demand.

What other choices do they have? In another of his blog posts, Murti discusses the volatility that energy transition portends and urges oil companies, as insurance against that, to simply sock away more cash on their balance sheets. Quietly leaving the money in the bank might also offer some insurance against a potentially hot and unpredictable summer.

More from Bloomberg Opinion:

- This Backdoor Keeps Russian Oil Flowing Into Europe: Javier Blas

- Russia’s War Draws Governments Into Energy Markets: Liam Denning

- Germany Will Struggle to Pivot From Russian Oil: Julian Lee

Traditionally, ConocoPhillips is evaluated separately from the other five as it is a purely upstream company rather than integrated. However, Conoco's sheer size — its market cap is bigger than BP's — and the fact that it was an integrated company back in 2008 means I include it here.

Aggregate oil and gas production for the six companies in 2008 was 17.67 million barrels of oil equivalent per day. Consensus forecasts for this year put it at 17.37 million barrels a day, about 2% lower (source: Bloomberg).

The tax break removed in 2006 dated from the 2005 Energy Policy Act, allowing two-year amortization of "geological and geophysical expenditure." This was extended to seven years for five oil majors. In 2008, President George W. Bush signed into law modifications of foreign oil and gas extraction income and foreign oil-related income. In addition, the (then) Section 199 corporate tax deduction, rising to 9% for most manufacturing sectors, was frozen at 6% for oil and gas producers and refiners.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.