Big Oil Is Unwilling to Bet on the Future of Crude

The reserves-to-production ratio, which gauges long-term prospects across the industry, has fallen below critical levels.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For a century, there’s been a key metric for judging the direction of the oil industry: The number of years it would take for wells to run dry.

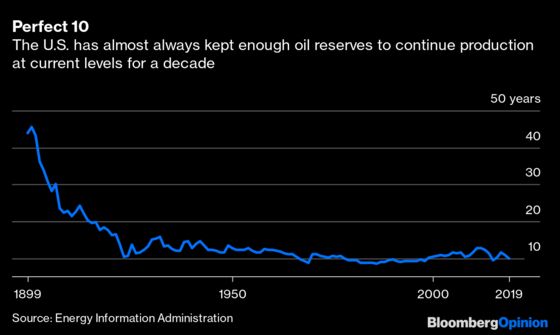

The reserves-to-production ratio or R/P — calculated as oil reserves, divided by annual production — has remained at eerily consistent levels since John D. Rockefeller’s day. At major oil companies and in the U.S. as a whole, it has rarely dropped below 10, and those moments have been associated with major disruptions.

When America’s R/P slipped below the critical level in the late 1960s, it came amid fears that the country might be approaching peak oil, heralding the heady geopolitics of the 1970s oil crises. When Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s R/P fell below 10 in 2004 due to a reserves writedown, the event was a major scandal, prompting the departure of a string of top executives and the payment of nearly half a billion dollars to aggrieved shareholders.

Now, Big Oil is running down its tank again. That's an indication that when executives say oil demand may have peaked and the world is transitioning fast to renewables, it’s more than just words. If you still think crude will see bright prospects in the 2030s, you should be exploring and developing the oilfields to supply it. As with the collapse in their non-maintenance capital expenditure since 2016, the erosion of petroleum reserves is a sign that even Big Oil is capitulating to the decline of its key product.

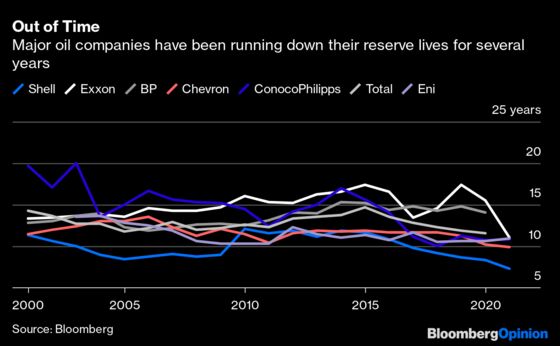

Take Exxon Mobil Corp., whose traditionally Texas-sized R/P hasn’t fallen below 13 years in data going back to 1993. The 15.2 billion barrels of reserves declared in its annual report last week would run out in 11.05 years at 2020’s production rates. At the average of the three previous, non-pandemic-hit years, it would run for just 10.62 years.

Chevron Corp.’s more modest reserve reduction announced the following day had the same effect, reducing its R/P to 9.89 — the first drop below 10 since at least 1998. Shell, meanwhile, has been running on fumes for some time. At the end of 2020, it was holding onto just 7.34 years of production, and Chief Financial Officer Jessica Uhl has declared the measure more or less irrelevant for the future of the business. “The reserves will be what the reserves will be,” she told an investor call last month.

While official figures for BP Plc and Total SE won’t be clear until they publish their annual reports later this month, all the supermajors appear to be trending in the same direction. BP’s production chief Gordon Birrell, for instance, told investors last September the company would target an eight-year R/P ratio, without giving a date for it.

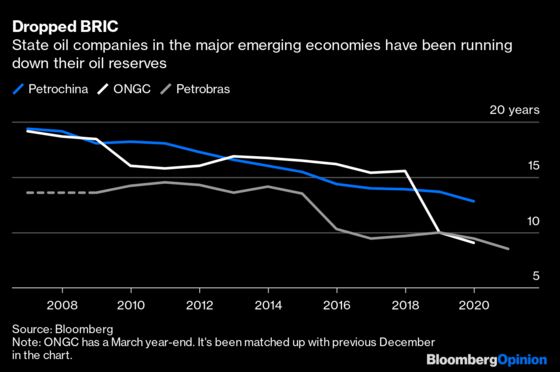

Things are little different at the non-OPEC state oil companies, which in the 2000s were seen by many as the future of crude production. Petroleo Brasileiro SA and India’s Oil & Natural Gas Corp. both now have R/Ps well below 10, while PetroChina Co. is heading rapidly down the same path.

On a national level, traditional major exporters such as Ecuador, Indonesia, Mexico, and Trinidad and Tobago, have all fallen below 10. If it wasn’t for the vast, multi-decade deposits in the Middle East and Russia — plus huge pools of heavy oil in Venezuela and Canada that may never be developed — the world would be looking distinctly short.

None of these numbers mean that oil production will stop when current reserves run out. The core business of resources companies is to constantly add to their reserves — one reason why U.S. crude supplies didn’t run out in the middle of World War II, as some of the earliest R/P ratios around the start of the 20th century would have suggested.

Reserves are also profoundly affected by expectations about where the oil price is headed. Technically, they’re the bit of an oil reservoir that companies expect to be able to produce profitably. That means a reduction in price estimates can push reserves into the red, causing petroleum to disappear with the stroke of an accountant’s pen, as my colleague Liam Denning has written.

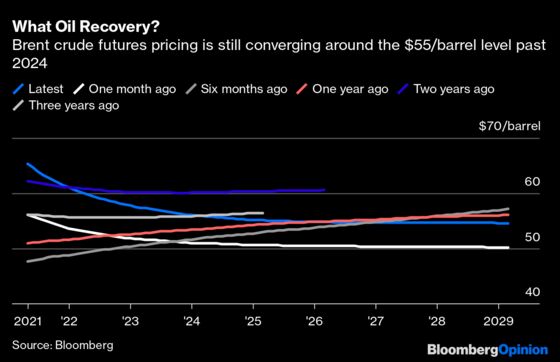

That raises the prospect that the climbing prices in recent weeks could cause these numbers to jump back at some point — but there’s little sign of that in the performance of longer-run futures, which are still around the same $55 a barrel level they’ve been languishing at for several years.

What does the demise of the R/P ratio mean, in that case? It’s not so much the death of oil, as evidence that the industry is unwilling to bet on its survival. Investors no longer want to see capital wasted developing assets whose profitability will depend on the state of crude demand more than a decade hence — especially when the world is trying to shift that demand into terminal decline.

The petroleum era is in its twilight years. Big Oil doesn’t want to get caught out when it ends.

Total’s number, which Chairman Patrick Pouyanne told investors last month was 12 years at the end of December, looks like the largest among the group, in spite of Total's plans to hit net zero emissions by 2050.

That's one reason why shale assets remain attractive, since their rapid depletion rates mean that developed reserves are consumed in a matter of years rather than decades.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.