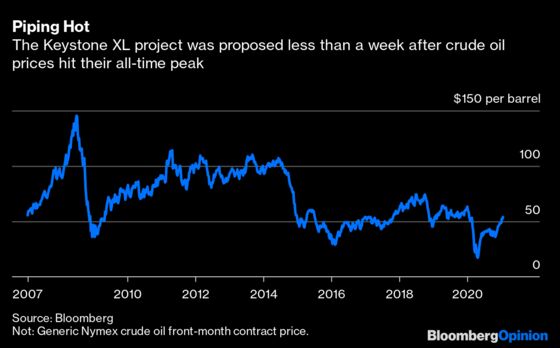

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In purely chronological terms, the opposite of a “Scaramucci” could arguably be called a “Keystone.” The Keystone XL pipeline expansion was first proposed almost 13 years ago. On Wednesday, newly installed President Joe Biden killed it. Again.

This one looks like the actual death knell. Certainly, the message from the market to TC Energy Corp. — the Canadian company that wanted to build Keystone XL — is to just walk away; the stock isn’t notably bothered by the pipeline’s latest demise. Such sanguinity speaks to how the world has changed since July 2008; a mere Keystone, yet so many Scaramuccis, ago.

That was a hot summer for the oil market.

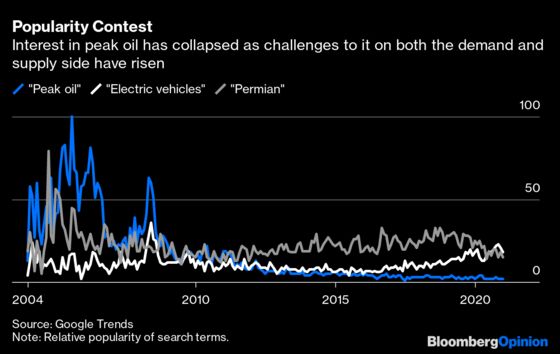

The oil price is only the most obvious difference, itself a manifestation of the bigger change. Fear of “peak oil” supply gave way to a growing expectation of peak demand. The intervening period has, among many other things, witnessed the resurgence of U.S. oil supply from shale; the emergence of electric vehicles exemplified by Tesla Inc.’s soaring stock; and the reformation of OPEC as a bigger group to deal with this changed world.

The political context has also been transformed. Since the failed attempt to pass cap-and-trade carbon emissions legislation in President Barack Obama’s first term, climate policy has become even more of a tribal issue (just like everything else). Obama ultimately used his executive authority to block Keystone XL in 2015. Notably, he justified it on the grounds of strengthening U.S. credibility in global climate negotiations. Under President Donald Trump, “energy dominance” dictated loosening constraints on the oil business, including using executive authority to revive Keystone XL. Now the president’s pen will work once again in the opposite direction.

In the background, two crises — one beginning a few months after July 2008 and another ongoing — have strengthened the role of government in influencing, or outright directing, economic outcomes. This has dovetailed with frustration at the lack of progress on addressing emissions and growing angst about economic inequality and environmental justice issues to produce a more radical progressive approach on climate, exemplified by the Green New Deal.

For the oil industry, there is a silver lining of sorts. The bull case for oil rests to a large degree on expectations that the “peak demand” argument is, at the least, premature. With oil companies under pressure to rein in spending, this tees up a potential supply gap and higher prices. Stymieing growth in Canadian oil production by blocking Keystone XL adds to this. That’s not great for Canadian oil firms with growth targets or the Albertan government that sank $1.5 billion into the pipeline plan itself. But for incumbent oil producers elsewhere, it offers one more support for prices in the near term.

Such thinking, however, is to compare Scaramuccis with Keystones. The broader sweep is that we have entered an era of relative energy abundance, as opposed to scarcity, and one where climate policy is tending more toward mandates than markets.

Keystone XL became a totem of the wider battle over climate a long time ago, symbolizing the entire fossil-fuel complex for environmental activists. Meanwhile, the counter-argument that it was vital in keeping pump prices down for American drivers was drowned in a wave of Permian barrels. Even if oil prices strengthen further from here, the dynamics of the market are very different from 2008. There are plenty of new barrels ready to be supplied for much less than $100, and these days they must compete on emissions intensity, too. On the demand side, whereas in 2008 the Tesla Roadster could satisfy the green-minded 1% and there was the hybrid Toyota Prius for the rest of us, this year will see the rollout of an electric Ford Mustang, for God’s sake.

Biden’s decision to can Keystone XL on Day One of his administration is telling. TC Energy had been carefully building up a political buffer in the form of agreements with U.S. construction unions and participation by indigenous groups, and then added the last-ditch measure of promising to power the pipeline with 100% renewable energy.

That Biden brushed all this aside without even going through the motions of a review is telling, suggesting he is prepared to move aggressively on delivering his climate agenda. Certainly, it suggests executive action will continue to play a prominent role, especially in the context of a finely balanced Senate, with implications for such things as fracking on federal lands and that other totemic project now on life support, drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

On that basis, another tool in the president’s Day One kit is worth highlighting; namely, re-establishing the interagency working group on the social cost of greenhouse gases. Rescinded by Trump, restoring this element to the permitting process effectively inserts a carbon (and perhaps methane) price into the cost of new energy infrastructure. Given the sometimes abstract concept of energy transition largely boils down to capital-spending decisions — what do we choose to build — this particular executive order would represent another means of curbing fossil-fuel growth by mandate rather than markets, per se.

We are a long way from the debates of the early 2000s. Keystone XL’s passing closes a long chapter in energy history. More importantly, it’s a prelude of what is to come.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.