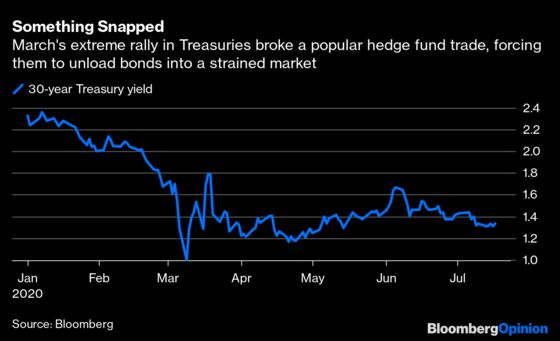

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Just a reminder from your friendly neighborhood former Federal Reserve Chairs: Hedge funds probably blew up the world’s biggest bond market in March and helped usher in unprecedented central bank action.

Ben S. Bernanke and Janet Yellen, who combined led the Fed for more than a decade, delivered testimony last Friday to the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis. Much of their remarks focused on the urgent need for Congress to take further fiscal action to offset the economic shock caused by the pandemic. However, in their writing on the Brookings Institution website, they also took some time to lay out their thoughts on steps taken by their successor, Jerome Powell, and his fellow central bankers.

Here is how they described the market chaos in March:

“Uncertainty about the pandemic led hedge funds and others to scramble to raise cash by selling longer-term securities. The upsurge in the supply of longer-term securities, including Treasuries, was more than dealers and other market-makers could handle. Key financial markets, including for Treasury securities, experienced substantial volatility. To stabilize these markets, which like the repo market play a critical role in our financial system, the Fed purchased large quantities of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, again serving as market maker of last resort.”

Mentioning hedge funds specifically is noteworthy, not because it’s new but because it’s not something the Fed usually does. Consider, by contrast, how the New York Fed’s Lorie Logan described those same events just two days earlier in a speech titled “The Federal Reserve’s Market Functioning Purchases: From Supporting to Sustaining.”

“The extreme shock to the economy and financial markets as the pandemic spread in early March led to a swift and severe deterioration in the functioning of the Treasury and MBS markets. Pessimism and uncertainty about the economic outlook as large segments of the economy were shut down, combined with concerns about markets’ ability to keep functioning in a remote environment, resulted in a strong desire for cash. In addition, the extreme volatility and its effect on risk metrics and margins meant that some normally profitable trades were no longer viable.”

In truth, neither of these accounts captures perfectly what happened, but at least Bernanke and Yellen refocused the conversation on hedge funds. Now four months removed from the worst of the market chaos, it’s worth stepping back and remembering what exactly transpired.

After all, at the time, equities were in freefall, credit spreads were surging and exchange-traded funds were deviating widely from their net asset values as investors desperately sought out liquidity. Any investor could be forgiven for not remembering that a little known trade popular among hedge funds, known as the cash-futures basis, was what set the U.S. Treasury market maelstrom into motion.

Because Treasury futures are much more liquid than the securities underlying them, the two will deviate in value occasionally. Enterprising investors, like hedge funds, can purchase the harder-to-trade bonds and sell the futures to earn that spread. However, because the difference is usually minuscule, the funds massively leverage up the trade with cash borrowed from the repo market. Basically, if there were a strategy perfectly captured by the cliché of “picking up pennies in front of a steamroller,” this would be it.

Suffice it to say, a lot of investors were making a grab for those pennies. JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategists in March estimated that leveraged funds’ exposure to the cash-futures basis could be as much as $650 billion. Heading into this year, it made sense: The Fed intended to keep interest rates steady while keeping a close eye on the repo market so it didn’t get unruly as it did in September (this was also probably caused by hedge funds leveraging up the basis trade). There was nary a steamroller in sight to derail this strategy, which in theory captures a nearly riskless profit.

Then, of course, the coronavirus pandemic happened and the trade blew up spectacularly. This set off a domino effect that nearly choked off funding for U.S. companies when panic was at its peak. Here’s Bloomberg News’s Stephen Spratt:

The spike in the spread last week as demand for futures soared caused the investors to hit the eject button on leveraged trades. Not only did they likely experience deep losses on their positions but the rush to close out helped further disrupt the gap between futures and underlying cash bonds.

Enter so-called real money -- larger funds who tend to invest in other products such as commercial paper and foreign exchange forwards. The spread between Treasury futures and cash bonds had now grown to a level that made the basis trade attractive to these unleveraged investors, all the more so given the risk-free nature of U.S. government securities.

The real money piled in, re-allocating investments from the commercial paper market in the process. That had a knock-on effect of sucking liquidity from a part of the financial system that provides corporate America with funds to buy inventory or make payrolls -- just when it needed it most.

This came out March 17. That same day, the Fed established its Commercial Paper Funding Facility. My Bloomberg colleagues published another article on March 19, in which Mark Yusko, the chief executive officer of Morgan Creek Capital, commented that “too big to fail is back, and this time it’s not the banks, it’s levered financial institutions.”

Four days later, the Fed announced open-ended purchases of U.S. Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities “in the amounts needed to support the smooth functioning of markets for Treasury securities and agency MBS.” It also unveiled facilities that could buy corporate bonds, a red line the central bank hadn’t crossed before.

It stands to reason that the cash-futures basis is what Logan was referring to in her speech when she said “some normally profitable trades were no longer viable.” Her speech largely reads as a “mission accomplished” of sorts, noting that the Fed is moving from actively supporting the markets to sustaining the gains of the past few months.

But it’s worth asking whether the Fed should be in the business of ensuring smooth sailing for this type of hedge fund strategy. Yes, it did what it needed to do during the worst of the market malfunctioning in March. But three months earlier, no less than the Bank of International Settlements called out hedge funds for causing strains in the repo market, where financial institutions like JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. are among the top lenders. The central bank is in charge of overseeing financial stability — this kind of leveraged arbitraging, to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars, would seem to be an obvious risk.

The good news, for now, is there’s little evidence hedge funds are piling back into the trade. The Cayman Islands, seen as a proxy for all kinds of leveraged accounts, was a net seller of long-term U.S. Treasuries in April and May. It shed more than $100 billion of the securities in March, far and away the most in history.

“What factors made these markets vulnerable to the abrupt deterioration in functioning that we saw in March? Could changes in regulations, data availability, or market infrastructure make market functioning more robust to future shocks? What role do funding markets play? These are challenging questions,” Logan said in her speech.

As Bernanke and Yellen pointed out, hedge funds would be a logical first place to look for answers. Once-in-a-century pandemic or not, Treasuries simply do not trade the way they did in March without something going haywire. Whether it was their intention or not, the former Fed chiefs deserve praise for bringing hedge-fund shenanigans back into the picture.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.