(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, German officials aren’t keen to show the U.S. much gratitude for the country’s reunification. Some Americans are outraged, but it’s worth considering where the thanks are really due.

On Nov. 2, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas published an op-ed in 26 European newspapers, calling reunification “Europe’s gift to Germany.” He thanked protesters throughout Eastern Europe and the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, for ripping up the Iron Curtain — but only mentioned the U.S. at the end, and only in the context of its technological competition with China.

That led Ben Hodges, former commanding general of the U.S. Army Europe, to tweet sarcastically:

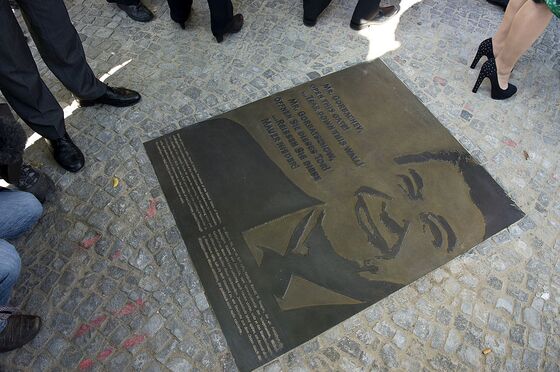

Mass’s op-ed isn’t the only place where Ronald Reagan, who famously exhorted Gorbachev at an April, 1987 event in West Berlin to “tear down this wall,” gets left out. The city of Berlin has also withstood years of U.S. pressure to honor him with a monument. On Friday, U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo will inaugurate a Reagan statue in Berlin, but it’s been installed on the balcony of the U.S. embassy — on U.S. territory, that is, rather than on city land. The Berlin city government, run by a coalition headed by the Social Democratic Party of which Maas is a member, believes it’s done enough to commemorate that speech with a plaque that was installed in 2012 near the Brandenburg Gate.

John Kornblum, a former U.S. ambassador to Germany, told the German tabloid Bild that Maas clearly was “afraid to say anything positive about America.” This captures the mood of many Social Democrats: They’ve never been as pro-U.S. as Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats, and they have especially serious issues with President Donald Trump’s America. But then, the roles of Reagan and his successor, President George H.W. Bush, whom some analysts believe Maas also should have mentioned since German reunification took place on his watch, probably aren’t significant enough to merit eternal gratitude.

Reagan bravely defied the advice of his State Department by uttering the line directed at Gorbachev. But it wasn’t really up to Gorbachev to tear down the wall. In 1987, East Germany was still run by Erich Honecker, one of the most rigid, Stalinist Warsaw Pact leaders, who vehemently disagreed with Gorbachev’s liberalization policies. Honecker was determined to stick to the old, repressive order. In his memoirs, Gorbachev described a cold personal relationship with Honecker, who, as the Soviet perestroika progressed, “pulled out of circulation the long-standing propaganda slogan, ‘learn from the Soviet Union.’ ”

Honecker only lost control two years later as the impatience of East Germans to get rid of his regime became too great even for his closest party allies. It was only then that Gorbachev “betrayed” East Germany, as Honecker’s successor, Egon Krenz, described it to a Russian interviewer this year. Krenz said he asked Gorbachev in November, 1989, whether he’d be “a father” to East Germany and received an effusively affirmative answer.

“I believed Gorbachev,” Krenz said, “and just two weeks later, Soviet representatives were negotiating with the West behind our backs and asking how much the West was willing to pay for the Soviet Union to agree to German unification.”

In reality, Reagan’s speech didn’t have any magical influence on East Germany’s collapse. Honecker, Gorbachev and Krenz were all overtaken by events. So was Bush in 1989. As the eminent U.S. historian Frank Costigliola wrote in 1994, Chancellor Helmut Kohl of West Germany had the greatest degree of control over the process — to the extent that it could be controlled at all, given the spontaneous upheaval that actually brought down the wall:

At two significant turning points — on 28 November 1989, when Kohl seized the leadership of the unification movement, and on 16-17 July 1990, when Kohl struck a final deal with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev — the Germans took advantage of circumstances to shape events largely on their own, and the United States had to adjust to the new realities.

According to Costigliola, the U.S. tactic of having “an arm around the shoulder” of West Germany was largely reversed during the reunification process:

Although the U.S. helped Kohl and [German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich] Genscher overcome Soviet, British and French hesitations about unification, America's influence proved to be a wasting asset. Even before the end of the 11-month unification period, the Germans were able, in deft and studiedly inoffensive ways, to maneuver between East and West.

The Bush administration’s goal wasn’t to help Germans reunite but to preserve American dominance in Europe, using the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as a vehicle. Kohl and Genscher enlisted U.S. support by submitting to that policy and used the Soviet Union’s de facto bankruptcy to get Gorbachev on board. But Kohl consulted no one before making a speech on Nov. 28, 1989, in which he laid down his plan for the reunification against Bush’s warning 10 days before to avoid any such rhetoric.

It’s unfair to praise Gorbachev for his role in bringing down the Berlin wall without mentioning Reagan or Bush — but only because it wasn’t his doing, either. The energy of the East German people who flooded through the gates on Nov. 9, 1989, and Kohl’s subsequent leadership created an outcome that probably wouldn’t have been possible had the process developed in summits and negotiating rooms rather than on the streets.

This doesn’t mean, though, that Germans shouldn’t be grateful to certain Americans for what happened. There is one who especially deserved a line in Maas’s op-ed: Bruce Springsteen, whose concert in East Berlin on July 19, 1988, was gate-crashed by more than 100,000 people without tickets in addition to the 160,000 who had them. The unprecedented loss of control on the part of East German police opened the doors to further street action. And Springsteen also made a short speech — unlike Reagan, in German:

It’s great to be in East Berlin. I’m not for or against any government. I came here to play rock ‘n’ roll for you, in the hope that one day all barriers will be torn down.

Throughout Eastern Europe, it was the people, not the politicians — and certainly not foreign powers — who won the Cold War. Maas was right to thank the Poles, the Hungarians, the Romanians, the Balts and the East Germans for their role. Those who, like Springsteen and other Western cultural figures, helped the people develop an appreciation for freedom, deserve an honorable mention, too. The leaders? Perhaps this is not the best moment to honor them.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.